When The Flaming Lips need a little jolt, they simply turn things upside down, or inside out. It not always easy for an already out-there group to find somewhere to go, to keep the record-making process exciting for 30-plus years. But these guys keep raising the bar on radical reinvention, for listeners and for themselves. The latest stage in the band’s evolution is The Terror, an album of songs inspired by specific sounds.

“As songwriters, we’re always mutating and evolving,” explains multi-instrumentalist/composer Steven Drozd. “We got to a point where it felt like we had a lot of music that was based on chord progressions. Then we got into deeper harmonic structures, and on the last record [Embryonic], we were doing these jams; they weren’t songs that we wrote, they were jams that we shaped into songs.

“With The Terror, we’d gotten to a point where we were tired of writing songs and then figuring out what the sound would be for the songs. We decided to go the other way. We’d find a sound—whether it was a synthesizer or a refrigerator or whatever—record the sound, and then try to make a song from the sound.”

For 15 years, the Lips have found an enthusiastic collaborator in engineer/producer/studio owner Dave Fridmann (Neil Finn, MGMT, OK Go), who records and mixes in his studio, Tarbox Road Studios (tarboxroadstudios.com), in New York state. “A song could start with somebody saying, ‘I’m really happy right now and I don’t know why. Oh, it’s because of the sound of the refrigerator running,” says Fridmann. “Then, it would be, ‘Okay, let’s start building a song around that.’ We’d mike up the refrigerator and start to develop a rhythm based upon what that was doing. It would snowball from that.

“There are a bunch of different songs on the record where we were trying to do one thing, but it turned into something else,” he continues. “Like we were trying to create a guitar loop, and someone accidentally plugged into a keyboard instead, and the level was way too hot, and one of the guitar amps would start freaking out, and then it was a manic rush to get a microphone on that amp before it blows up. Sometimes it would be like, ‘I don’t know what we’re going to do with that, but we’re going to do something with it, because that’s the weirdest sound we’ve heard in a while. And before you know it, we’re working on lyrics.”

“Sometimes the sound tells you what the song should be about,” says Drozd. “There’s so much in a WASP mono synth running through an old analog delay or a shitty old amp. That sound could be telling you something, without you having to write chords or anything. This was really fun for us. I felt like we were doing something new and different for us.”

It would seem that this “process” of song invention could result in a collection of random, disparate tracks, but that’s not the case. The Terror is out there, for sure, in a spacey, psychedelic way, but the songs coalesce rhythmically and sonically because the bandmembers made a conscious decision to repeat certain musical elements they loved, to unify the songs and to keep some great sounds going. One of the most central pieces during composition and recording was the creepy, retro-futuristic sounds of an Electronic Dream Plant (EDP) WASP monophonic analog synthesizer.

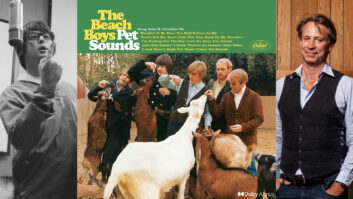

Wayne Coyne and Steven Drozd using the Electronic Dream Planet WASP and Yamaha CS-60 synths, respectively.

Photo: Dave Fridmann

“Instead of opening something like [Propellerhead] Reason where you have literally thousands of sound options, we’d turn on the WASP, and no matter what you do with it—all the cool things it does—it’s that instrument,” Drozd says. “These old mono synths have such nice characteristics. We used it on almost every track, and if we didn’t have it on a track, we would add a little bit just to tie the songs together.” The WASP, a gift to the band from Sean Lennon, had actually become a bit of a museum piece. “[Sean] was like, ‘You guys like this thing? Really? You can take it.’ We took it home and just coveted it,” Drozd continues. “We had it sitting in a corner, but Wayne [Coyne, Flaming Lips frontman] was like, ‘Let’s take this f**cking thing out and use it instead of staring at it.’

“I would say there were four keyboards that shaped the whole record, and that’s how we did it instead of being all over the place with acoustic guitar on one song and electric guitar on another,” Drozd adds. “There’s actually very little guitar on the whole record. We decided to keep it all in the same basic area.” Other keys that played big parts on The Terror were a Yamaha organ that Drozd purchased on eBay, and Fridmann’s Yamaha CS-60 and ARP 2600.

“You can plug any one of those things in, and it will sound like a time machine,” Drozd says, “like some future a thousand years from now when we’re all living in space—a super lo-fi, sci-fi movie kind of thing.”

Capturing the Lips’ sessions involves more perversion of the tried-and-true, but Fridmann is in for all of it. This time out, the band tracked mainly in Tarbox’s Studio B, a newer room that gives Fridmann and his clients additional flexibility.

“Tarbox is built in a former home where we changed around the way it was set up,” Fridmann says. “The house’s original master bedroom/bath combination are my control room, and the living room—with a big, open cathedral ceiling—is our main recording space. But acoustically, before we built the B room [in 2010], if somebody was in the house making music, we all knew they were making music. That can be a good thing with the Flaming Lips, because everybody’s always involved in everything that’s going on. But now, with the new building, we have a space where bands can be rehearsing or writing while I’m mixing; they can make all the noise they want and I can’t hear it.”

“In 2011 when we were working on this 24-hour song [“7 Skies H3”], we had three studios going,” Drozd recalls. “There was the main room where Dave would be assembling the whole thing and recording. I would be in Studio B working on other parts, and then Wayne or Michael [Ivins, bassist] or Kliph [Scurlock, drummer] would be in a third room. The studio can see a lot of activity at the same time.”

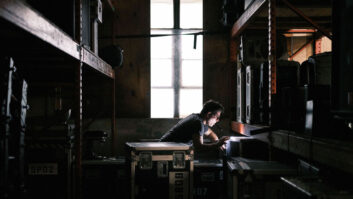

Dave Fridmann in Tarbox Road’s Studio B.

Photo: Mary G. Fridmann

In addition to Studios A and B, Fridmann says that every room at Tarbox is wired for tracking, and that the band will record in any corner of the house, and place microphones at any position or distance they like. For example, setting up a conventional drum kit—with close mics, overheads and room mics—just isn’t done.

“In fact, they won’t allow that,” Fridmann says. “I can use DPA mics from afar if I’d like, or use STC ball and biscuit mics from across the room. That’s fine. But no conventional miking techniques were utilized in the making of this record. Not that I’m against it. I use more standard setups with other bands all the time. But with these guys, we just have a bunch of microphones set up, not in any particular order and not in any particular room. The drummer and bass player might play with one microphone somewhere between the amp and the kick drum, and that’s the drum sound and the bass sound. We’re done.

“Our technician, Greg Snow, has made and modified lots of different microphones—military ones and Motorola dispatch microphones—and used different circuitry. I don’t even know what’s in there, but they sound amazing! You can record from across the room because there’s some weird built-in compressor already in there. So when the Lips say, ‘We’re not going to go sing into that microphone. We’re going to sing over here,’ we can do it, and we end up with some very unusual sounds.”

“In this day and age, it really is easy to record a great-sounding guitar or a great-sounding drum kit, especially with someone like Dave Fridmann, who’s just at the top of the field,” Drozd adds. “So part of the fun for me is to bring Dave some shitty sounds. One of the songs, ‘You Lust,’ starts off with a couple of us in a room playing synth sounds into Wayne’s iPhone. Dave took that off the iPhone, compressed and EQ’d it, and there you go. It’s the beginning of a song.”

Most of the tracks were recorded to Pro Tools HD and mixed on Fridmann’s Otari Concept Elite board, but Fridmann points out that changes and new sounds are on the table at all times.

“Even when we used to track to 24-track analog tape,” he says, “we’d fill 23 tracks, and then with the 24th track, someone would say, ‘That’s what we should have been doing all along,’ and we’d throw everything out and start with this new thing. They’re always following their instincts to the song, and we might write a set of lyrics and do background vocals and overdubs and figure out effects, and then throw it all away and start with some other new, weird sound that we thought of and recycle part of those lyrics and turn those into the bridge of another song. It’s a very nonlinear process all the way through.”

“What’s great about Dave is that he’s like us, in that he’s been at this a long time, but still, to this day, he’s as curious about music as an 18-year-old,” Drozd concludes. “So when we get together we’re on the same page, and there’s a lot of energy and a lot of excitement that maybe a lot of bands our age don’t have. Dave has such a genius mind for this kind of thing. Some people hear music and just imagine chords and melodies. When Dave is listening he’s always analyzing. He’s thinking about how it can work sonically. He helps with arranging. He can help shape a melody. We’ve been friends for so long that he’s like a bandmember.”