We seem to have entered an age where more people are talking and fewer people are taking the time to stop and listen. It’s be- come true across both the cultural and political landscapes, on a local and national level. There seems to more noise and chatter everywhere you turn, to the point that it can become difficult to pick out nuance, subtlety, quality…or simply a good song. The bombardment of media and messages can reach the point where a person just wants to Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out, to echo an earlier generation.

That’s why it was so refreshing this month to touch base with two friends, one old one new, both top-quality mastering engi- neers, and talk about Listening. Actually taking the time to lis- ten. The daily life of a mastering engineer involves intensive con- centration and acute listening. It involves dialing in minute EQ or compression adjustments in a particular frequency and rec- ognizing the whole of a musical piece. It involves isolated head- phone playback and high-end monitoring in a room that is true. It is truly hearing the forest and the trees. Often they work alone. Mastering engineers have to take the time to listen.

First, Michael Romanowski, a longtime Bay Area buddy who shares my Midwestern roots, hailing from Kentucky and Nashville. He owns Coast Mastering in Berkeley, and he’s active in the Recording Academy, the Bay Area recording community and in the classroom. He’s passionate and conversant about 1⁄4-inch tape, lacquers, streaming and hi-res audio. And he is passionate about listening. Active listening. He has students search for things to hear, then pay attention, then describe what they hear. He often equates learning to listen to learning about food and wine, or mastering a sense of feel and touch, or smell. Developing any of the senses helps to develop all of the senses, he believes. All improve an engineer’s sense of perception.

Michael shares his thoughts in a feature this month on Listening, page 32

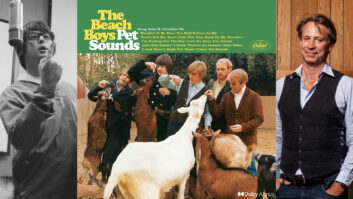

The second engineer is the incomparable and on-a-roll Dave Kutch out of New York City, pictured on this month’s cover enjoying a fine cigar. Ten years ago he opened The Mastering Palace in Harlem, following stints at Tiki, The Hit Factory, Powers House of Sound, Masterdisk and Sony. He learned from the best, and he soaked it all up. On his very first paid gig, at the age of 20, Phil Ramone was producing Debbie Gibson, with Fred Guarino engineering. The most important among a thousand things Ramone taught him, he says, was to “trust your ears.” It’s not about meters or a scope, he learned. If it sounds good, press Record.

“I tell people today that my left hand can be my most valuable tool,” Kutch says, “because I use that hand to cover my eyes and just listen. You have to trust your ears. And you have to trust the musician within yourself. There comes a point when you have to forget that you’re working on a song, or that you have a million plug-ins in front of you, or you have that one EQ for the bottom. It really becomes as simple as a set of speakers, and the song is mak- ing my body move. My booty is shaking. It feels good, it sounds good. It’s hitting me just right. It’s done. It’s music.”

The process of making music involves many different kinds of listening, from recognizing the tonal changes in moving a microphone even a few inches to balancing clashing frequencies in a complex mix and bringing out the vocal. For a mastering engineer, it’s all about presentation of the music, and how that music is to be perceived by the listener.

And to know how music is perceived by the listener, you have to sometimes stop and do a little listening yourself.

.