The brilliant and innovative guitarist John McLaughlin has alwaysfollowed his heart. Beginning in England during the late ’60s, he wasexperimenting with blues and avant-garde jazz/rock with Alexis Korner,Graham Bond, Ginger Baker, John Surman and others. Not long after that,he ventured to the U.S. and joined wunderkind drummer Tony Williams’groundbreaking fusion band, Lifetime. From there, he was recruited bythe great Miles Davis to be part of his stellar experimental sessionbands for the landmark albums In a Silent Way and BitchesBrew. McLaughlin made some serious waves of his own in 1971, whenhe formed the revolutionary and highly influential fusion unit,Mahavishnu Orchestra. Within a few years, however, this restlessmusical spirit had moved onto other horizons, forming theIndian-flavored acoustic jazz outfit Shakti, a group he has returned toa number of times through the years, even as he has gone on to otherexciting musical explorations with many inspiring musicians from thejazz and rock worlds.

Differing greatly from most of the discs in his illustrious catalogare two recordings that are based around classical music:Apocalypse (1974) was his most adventurous album during thesecond edition of the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Its orchestral work wasconducted by Michael Tilson-Thomas and grounded by the driving fusionof his new band, which featured violinist Jean-Luc Ponty and drummerNarada Michael Walden, among others. His second symphonic album,Mediterranean, recorded in 1988, also featured Tilson-Thomasconducting the London Symphony, but it was texturally much lighter thanApocalypse, based around an appealing neo-romantic guitarconcerto.

Fifteen years later and for the third time, McLaughlin has returnedto the orchestral format with Thieves and Poets. The guitarist’sfirst new studio project in almost six years features an orchestraknown as I Pommeriggi Musicali di Milano (Musical Afternoons in Milan),conducted by Renalto Rivolta. However, this CD differs from hisprevious classical works for its inclusion of four standards dedicatedto four legendary jazz pianists: Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, BillEvans and current Cuban sensation, Gonzalo Rubalcaba. Accompanying themaster guitarist for that portion of the CD are old cohorts theAighetta Quartet with Helmut Schartlmueller on acoustic bass.

When I caught up with McLaughlin in Boulder, Colo., where he waspreparing for a tour with the latest incarnation of Shakti, he relatedhis surprise that it’s been a decade-and-a-half between his orchestralforays, noting, “They’re all so very different. The first was abig electric band with orchestra. The second one was disappointing: Iliked the piece, but I had no hand in the mixing and would havepreferred another result. Maybe that’s one of the things that made meproduce this one in the manner I did — using orchestra in one wayand sound design in another. Despite the density and dynamics of theorchestra, I’m able to get a coherent balance between the instruments,soloists and the mass that the symphony can come up with. You have thistremendous feeling of tension between them and the solo voice, but Ilike that.”

Thieves and Poets is, in essence, a three-part suitechronicling the guitarist’s musical journey during his lifetime. Thefirst movement represents Europe, the “Old World”; thesecond is the transition to America, the “New World”; andthe third is firmly set in the “New World.” The finale is ajoyful unification of both worlds. Creatively and technically, it’sderived and modified from a work originally commissioned by JurgenNimbler and the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie. Once completed, with thehelp of Yann Maresz, his former student, McLaughlin toured with thesymphony for performances throughout Europe. He called it “one ofthe greatest musical experiences of my life.” However, once theconcerts concluded, he shelved the composition and moved on to otherpursuits. Several years later, he dusted off the work, and again, withMaresz’s aid, re-orchestrated it for a large symphony concert in Pariswith his old friend, guitarist Paco de Lucía.

After that incredible performance, McLaughlin shifted his attentionto other creative directions. Then, Jean-Christophe Maillot,choreographer of Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo, the city that theguitarist also calls home, asked if McLaughlin had a piece fororchestra that he could choreograph. By this time, the composition wasdramatically different from the initial conception — it neededrevamping — and McLaughlin hadn’t been able to set aside time tosolely focus on it. By the time he finally completed the work, it hadbeen three years since its inital conception.

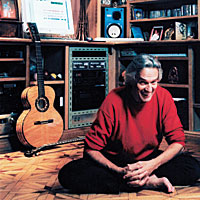

In the beginning stages, McLaughlin worked off of a demo usingsynthesizers and samples, detailing the parts through MIDI for RenatoRivolta, who’s also a jazz musician. Under the conductor’s leadership,the orchestra recorded to Pro Tools in Officine Meccaniche Studio’shuge wood-lined room in Milan where McLaughlin had previously cut hisCDs Time Remembered and The Heart of Things.

“Having a jazz player conducting the orchestra was great forme,” McLaughlin comments, “because rhythm is veryimportant. Not that I wanted them to sound like a jazz band, but Iwanted them to keep pretty good tempo. They did a great job and had alot of enthusiasm. And the soloists were outstanding and contributedwonderful playing.” Due to scheduling conflicts, some of thesoloists’ parts were recorded later by McLaughlin separately at hishome studio.

Additional orchestral elements were created in the studio, withMarersz playing a major role. “Strings and timpani can’t bereproduced,” McLaughlin explains, “but there still are alot of things that you can do, and we, in fact, created our owninstruments. We were using Pro Tools, and Yann is an expert with thisMac program that applies MIDI and its controls but in an acousticenvironment. Still, it’s major work and you must have a tremendousnumber of samples to get the right dynamics and timbre. Truthfully,it’s more work than recording a symphony and I thought about flying ina big band to overdub on top of the orchestra, but I was already wayover budget.”

Not to be overlooked is the standards segment of the CD, which paystribute to four keyboardists whom the guitarist greatly admires.McLaughlin says that he can’t explain why, but he often feels a need torevisit his past, and classic American songbook material was what hewas weaned on as a young jazz player in the ’60s. In a way, thesesimpler, more modest tunes pick up where 10 years after his acclaimedTime Remembered left off. But they, too, proved taxing forMcLaughlin, both in terms of composition and time. Each selection tookroughly a month to compose and then condense through a lot of trial anderror and rewriting.

Mixing was done in Pro Tools, mostly during September and October of2002. Though McLaughlin is actually quite adept on the hard disksystem, with more than 10 years of experience, he relied on Austrianengineer Marcus Wippersberg’s talents for mixing, editing and someoverdubs. Wippersberg, who’s a rock drummer by trade, had never metMcLaughlin or worked on a classical-based project before. From his homestudio in Linz, Austria, situated between Vienna and Salzburg, herecalls how he ended up working with the renowned guitarist: “Imet John during the middle of the work on the CD. He had alreadyrecorded the string orchestra and his guitar on his own. I was workingin Monaco with another guy in a studio for a Narada Michael Waldenproject. They came into contact with John, and he was looking for anengineer to work with.”

As a result of that meeting, Wippersberg soon found himself deeplyimmersed in McLaughlin’s vision. He worked 12-hour days at theguitarist’s side in Monaco and at his own similarly equipped studio inAustria, conferring long distance with the guitarist about bothtechnical issues and creative matters. “John really knows what hewants and he also knows a lot about the Macintosh operating system andother things,” Wippersberg says. “It wasn’t, ‘Do whatyou like and I’ll tell you if I like it.’ He’s mixing with youall the time.” Wippersberg felt the four standards were fairlyeasy to put together, but the three-part suite and finale, withorchestra, soloist and extensive sound-designed portions programmed byMaresz, were extremely challenging to mix. “Getting those threecomponents to sound like one orchestra playing was difficult,”the engineer comments. “Basically, I couldn’t have done itwithout the Altiweb plug-in. It made everything sound like it allhappened in the same room, and I’ve used it on every record I’vemixed.”

Wippersberg is the first to acknowledge that working on Thievesand Poets was a far cry from the rock and soundtrack sessions henormally does. It was a tremendous learning experience for him andquite inspirational: “It was really beyond belief! I would besitting in the library of his house in Monaco where he has his ProTools setup and he’s behind me playing his acoustic guitar! The bestpart was recording his solos and getting to decide which one would beon the record. I’d definitely like to do more work with him.”

When we spoke, McLaughlin was already focused on his next project,which he hinted would be a drastic mixture of styles sure to inflamecritics. Summing up Thieves and Poets, he states, “I wouldsafely say that this is my last swim in the classical swimming pool.I’m 62 and I can’t see myself doing another one 14 years from now. Butthrough classical is how I first fell in love with music. It was onlylater that blues, jazz, flamenco and Indian came in. But out of themall [his classical albums], I’m the happiest with this recording. Andin the end, that’s the only thing I can really hang on to. I’ve had myshare of flack thrown at me by record companies. But in the generalsense, I have to make myself happy; otherwise, I wouldn’t want torelease it.”