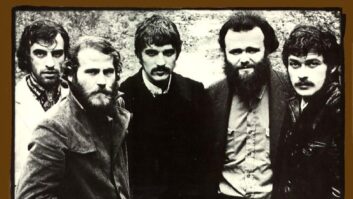

Acclaimed by many as the greatest rock concert film ever made,

The Last Waltz — director Martin Scorsese’s riveting

depiction of the Thanksgiving 1976 farewell concert by The Band and a

gaggle of their musician friends — was a natural candidate to

make the jump to multichannel formats. Last fall and winter, the film

was completely restored and remixed. It enjoyed a brief run in selected

theaters this past spring, and was released by MGM Home Entertainment

on DVD in both 5.1 and conventional stereo. Additionally, Warner

Bros./Rhino came out with an expanded four-CD version of the popular

soundtrack.

As is usually the case with these sorts of

restoration/remastering projects, nothing was as simple as it seems.

But then, neither was the making of the original film, which, despite

its relatively straight documentary approach (with minimal additional

interview footage), sprawled over 18 months from the winter of ’77

through the spring of 1978.

“Everything was pretty much state-of-the-art for the

time,” remembers Steve Maslow, the veteran re-recording mixer who

mixed the music for the original film on the Goldwyn stage’s Quad 8

console. “They brought it in on [24-track], and initially they

wanted to do something that wasn’t done too much then — it might

have been one of the first movies to do it — which was to

interlock the multitracks to the film chain. It was quite cumbersome at

the time. I can’t even remember what they used — some sort of

film sync lock device — and it took at least 20 feet for the film

chain to lock up; it was pretty frustrating.

“It was quite time-consuming taking the [multitrack]

information and locking up the film channel and going to 3- or 4-track

mag. We EQ’d and made a little mix predubbed to 4-track mag, which

became the dubbing unit. We had almost two months of premixes, getting

everything from 16-track to the film, and then there was a little time

spent getting the production dialog from premix. Rob Fraboni, who was

the music producer, was involved almost from the beginning. Robbie

[Robertson, leader of The Band and producer of the film] showed up at

the final, mostly.

“The length of the mix was the longest I’d ever been

on,” Maslow continues. “It was six months, done mostly at

night. I had three days off: Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s.

One reason the film as a whole took so long is [The Band] took the

tapes to their ranch and messed with them for a year, overdubbing bass

and keyboard and vocal parts. I remember one of the problems we had to

deal with was that Rick Danko had all-new bass tracks, and he

overdubbed them without regard to the sync fingering onscreen. So part

of what I had to do was every time he was on camera, I had to switch

from the overdub bass to the production bass and make it sound

seamless, which wasn’t easy because it had a slightly different quality

to it. As I recall, there were also quite a few piano overdubs, too,

but since you never saw Richard Manuel’s fingers, that wasn’t a

problem.”

Maslow, who had a background in conventional music mixing before

making the move into film, says that mixing The Last Waltz

“was incredibly challenging because there were a lot of really

interesting camera moves, and Scorsese wanted the sound to reflect the

movement onscreen. So, for instance, there might be a sequence where

the camera was moving, say, stage left to stage right with a sweep, and

we would actually pan the instrumentation and vocals with the camera

move. That was something I don’t think had been done before in a

concert film.

“Of course, in those days, we had no automation,” he

adds. “It was rather primitive compared to today. So there were a

few times when we had three, four, five people on the console handling

different instrumentation or vocals on the mix. It was quite a scene.

Very difficult to get that right, but also fun. The teamwork becomes

very important,” he says with a laugh. “Dolby had

just introduced surround, but we did what was essentially a 3-track

left-center-right stereo mix. There were no discrete surround tracks at

the time.”

Now flash forward 25 years and head out to nearby Santa Monica’s

Pacific Ocean Post (POP) Sound Studios, where Ted Hall remixed The

Last Waltz in surround for both its theatrical and 5.1 DVD release

under the supervision of Robbie Robertson. Hall, who was widely hailed

for his expert surround job on Yellow Submarine three years ago

(see Mix, September 1999), had his work cut out for him.

“What came to me were from the original 2-inch masters

transferred to Sony 3348 HR 24-bit,” he says. “And,

unfortunately, when they transferred the tapes, they ran the tapes

wild, so I had to resolve the tapes from the timecode on a digital

track, which was difficult. But once I got that up, there were issues

of music edits and sorting through the tapes and doing a lot of

archaeology to find out what was used. For instance, what vocals they

actually used, because they overdubbed them on some songs for the

[original Last Waltz] soundtrack album. Robbie’s mixer, Dan

Gellert [see “Remaking the Music,”, below] did stereo mixes

and made stems, splits — splitting out the guitars and

everything. He is the hero in this; his attention to detail is

outstanding. That was approved by Robbie soundwise and stereowise, and

then I made a 5.1 to match the original mix to some extent. That

original mix, which Scorcese worked on back in ’78, was a stereo mix

with lots of panning. So if the picture moved from the piano to the

guitar, the sound would move with it.

“Part of my job was not only to get everything in sync and

to get a nice-sounding 5.1 theatrical music mix happening, but to

re-create all these pans. I took the VHS release tape home for a couple

of days and mapped out as much as I could of what Steve Maslow had done

20 years ago; it was a humbling experience in this era of massive

automation and data networks. Some songs were pretty static, but almost

every one of them had some sort of dynamic panning going on. We mixed

everything digital on a Neve Logic 2 console with all panning, EQ,

dynamics, automated. I would go through the mix, get it to where I

thought it was working and then call up Robbie, and he’d drive over,

we’d run through a couple of songs and tweak. We’d listen in a

theatrical environment, and he was really good at picking out things

that involved the sound in a theatrical 5.1 environment. He’s a very

attentive, great guy. Everything he said was always totally

right-on.

“Eventually, before it was released, I made 5.1 stems and

took those to Andy Nelson at Fox, and we played it in a huge

room there just to give it its final little blessing and make sure that

everything translated well. It’s funny, I was working with old

¾-inch picture for the longest time. I didn’t actually see the new

picture until we went to Fox. And when I saw it there, I was

stunned.”

According to Hall, “Robbie’s whole intention with the 5.1

mix was to try to make you feel like you were there; he wanted it so

that after 90 minutes in the theater, you felt like you were at a

concert. The way we mixed it, it’s a little bit like you’re standing on

the stage and the band is around you. While most of the music is still

up front, there’s also music in the rears pretty much all the time;

there’s reverb, some drums and whatever the instrumentation is that

seems to wrap you into the mix, whether it’s a guitar or keyboard part.

There’s also very discrete crowd stuff going on [in the rears]. In

fact, there’s one guy who’s whistling all the time that drove me

absolutely nuts. The same whistle over and over again. Even Robbie was

saying, ‘Can’t you notch that guy out?’” Hall says

with a chuckle. He also notes that because Gellert “had mixed it

in more of a studio album style, for the 5.1, I tried to match the

ambience of the room [Winterland in San Francisco] using a couple of

processors to give it a little more of a live feel.

“Robbie was intent on really restoring this the right way,

so we took the time to do it right. I spent a lot of time getting the

original mix together and then probably another month mixing the music.

Dan would be working across town, and if there was anything I needed,

he’d send it to me and vice versa; we were swapping files. Getting the

movie just to where it should be before the 5.1 [work] took a while.

What Robbie wanted to do on the DVD was have a new 5.1 mix and the

original 2-track mix, mastered and EQ’d. That way, people at home can

listen to what it originally sounded like. And the people with surround

systems will definitely hear something exciting and new.”

THE WINTERLAND RECORDINGS Elliot Mazer’s Live

Elliot Mazer was the chief recording engineer for the live concert

that is central to The Last Waltz. In his words…

I had worked with The Band previously and had known them from

Woodstock and Albert Grossman’s office. I helped them with Music

From Big Pink, mostly around mastering time. They had mixed it, and

Robbie [Robertson] was concerned about how dull and dark it was. We

listened in my apartment and in the studio, A&R Studios, the old

Columbia studios on 7th Avenue. Turns out that it sounded dark and it

sounded great. They had not planned it that way, but the engineers that

worked on it were very conservative about EQ. A lot of it was done live

in the studio, and the 8-track multitrack tapes were worn. All of which

can make a project sound dull.

I also helped John Simon get the equipment and set up the studio for

their second album, The Band. It was recorded in a home in the

L.A. hills that had been built for Sammy Davis, Jr. And I had recorded

a live show with The Band at Wembley Stadium [London] in ‘74. So

I knew Robbie and The Band, and I was called in to record The Last

Waltz after Robbie and Rick heard Neil Young’s Time Fades

Away.

We met in L.A. at Shangri La, The Band’s studio in Malibu, and

talked about the show and traded ideas. Marty [Scorsese] had prepared a

shooting script that was based on the lyrics of each song. The camera

assignments and moves were built around the songs. We worked the setup

at Winterland, all the rehearsals at Winterland and the evening

rehearsals in the basement of the Miyako Hotel, which were magical.

The truck was one of Wally Heider’s trucks. Rob Fraboni mixed the

house sound at the gig. John Simon did many of the arrangements,

conducted various parts of the show and was very much involved with the

rehearsals. He had to teach the guest songs to The Band and worked with

the horns. John also played piano on a few songs in the show. Rob and

John also worked on the overdubs and mixes for the original LP.

The Heider crew was great. Ray Thompson, one of the greatest live

engineers, set up the piano sound and the house mics for the show. He

could not be there for the actual show, but he was very helpful.

I was responsible for the concert recording. Every aspect, every

detail of The Last Waltz was discussed and planned out to

perfection. We knew the entire show before it started. There was one

song in the show that had problems: Paul Butterfield walked out to the

wrong mic, Robbie broke a string and one of Marty’s lighting rigs went

down — all of this at the same time. By the time Robbie got new

strings and Butter was on the right mic, most of Marty’s cameras were

out of film. Marty told Robbie to go, and he covered the song with one

camera, I believe, until the crews had time to load new magazines on

the other six cameras.

The tape format was 2-inch, 24-track on 3M machines with Dolby A

noise reduction. We had two machines running on overlap, and I think we

got every song on both machines. But at some points, the power dipped

so low that on a few tracks we had hum since the Dolby units were not

connected to the same power source as the machines and console.

The vocal mics were Beyer ribbon models. The Band had great mic

technique, and these mics had good off-axis response, which allowed for

a lot of jumping around — the singers didn’t have to eat the

mics. We had mics from my studio, His Masters Wheels, the Heider’s mics

and the P.A. mics. We even painted the mic stands black so that they

did not glare on film — Keith Monks stands and booms! So as not

to screw with Marty’s shots, we put up no drum overheads and put mics

under the cymbals facing up instead. Levon’s vocal mic gave us an extra

amount of air on the drums.

We used every input on the API Heider board, and I believe that I

used my Neve BCM 10/2 for additional inputs. We mixed the drums to four

tracks and everything else was isolated. No compressors, no gates and

generous EQ.

REMAKING THE MUSIC

As independent engineer Dan Gellert tells the story, he first met

Robbie Robertson when The Last Waltz project was in the planning

stages. Robertson needed an engineer to remix the entire original album

for both an expanded CD re-release and the remastered film soundtrack.

Also planned was a DVD-Audio release (in 5.1 surround), which, like the

four-CD boxed set, would include a slew of previously unreleased

performances. “It was a long process to do, for sure,”

recalls Gellert, who eventually spent about 125 days working on the

various remixes.

Originally from New York, Gellert started his career at the Power

Station (now Avatar), eventually reaching the position of chief

engineer. After developing a roster of clients while at Avatar, Gellert

went independent about two-and-a-half years ago. Recent projects have

included remixing tracks for two Robbie Robertson projects, mixing an

album for Sweet Honey in the Rock and recording jazz pianist Akiko

Grace with her trio.

Gellert joined The Last Waltz project after the original

tapes — including five hours’ worth of 24-track multitracks from

the concert, plus the “Last Waltz Suite” and other tapes

recorded on a Hollywood soundstage after the event — had been

transferred to 48-track digital format. “The signal chain was as

clean as possible, just straight into the Sony 3348, which is

24-bit,” explains Gellert. “Unfortunately, I was brought

into the project just as the transfers were done. [I say] unfortunately

because the transfers weren’t done perfectly — not the audio,

which was fine, but the clocking, which was a problem. We had to figure

out how to fix that in the end when the music got synched to

film.”

Gellert’s first task was to listen to all of the tapes to find the

correct performances to mix for the film soundtrack. “There were

a lot of extras — a lot of tapes, a lot of outtakes — so I

had to weed through it all to see what would make sense,” he

says. Not surprisingly, documentation was less than comprehensive.

“With anything from that long ago, the first thing to go away is

the documentation, the track sheets. We had 50 or 60 large reels of

48-track digital multitracks, so I started by going through them to

find the extra bits, and some bits that no one has heard. So that was a

long process in and of itself, just listening.” Not only were

there duplicate tapes to sort out, with no documentation to show which

was the master, but occasional musical patches, overdubbed on the

master tapes after the concert, had to be identified and logged.

“It went in stages,” recalls Gellert. “The first

stage was the transfers, and then I got all the tapes. Then the next

stage was listening to everything before I started delving into mixing

it. Finding out what was going to be useful and then creating a

schedule for mixing it all. We decided to mix the original album first,

then the extra stuff and then what was in the film that wasn’t on the

album.

“My original plan was to mix each song in stereo and then go

to the surround version. But after the first one or two songs, I

realized this was not the most efficient way to do it,” he

continues. “I found that for this kind of project, mixing in

surround is such a different beast. The subwoofer excites the room in

such a different way that to go between the two formats quickly wasn’t

efficient — you had to get your head around the room sounding

very different. So, I mixed it all to stereo first; all of the original

album, things in the movie that were not on the original album, the

extra stuff I found, like the jams and rehearsals and ‘The Last

Waltz Suite,’ everything. Then I went back and concentrated on

the surround mixes.”

All the mixes were done on an SSL Axiom MT digital console, with

stereo mixes committed to an Ampex ATR-102 running ½-inch analog

tape. “We mixed to other formats, but that’s what ended up

winning for the stereo,” comments Gellert. Surround mixes were

captured in 24-bit Pro Tools sessions. All stereo mixes were monitored

on Yamaha NS-10s, while Gellert set up Genelec 1031s and a matching

subwoofer for the 5.1 surround mix.

The private studio was well-equipped with a combination of classic

analog devices and the latest digital processors. “One of the

great devices that I really enjoyed using was the Sony S-777 sampling

reverb,” he says. “It just sounds accurate, like you’re

actually in the space. I used that a lot, and a Lexicon 960.”

How did Gellert approach the remixes of an album that many consider

a classic? “I started out listening to the original. I wanted

this version to bring out all of the musical detail that was masked in

the original, and also to have a real impact. That was my

agenda.” To achieve consistency with the rhythm and vocal levels,

Gellert used some compression but more often relied on fader rides,

which were captured and repeated by the MT’s automation system.

“Compressors would level it out a little bit, but to make it

really level out was just eating up too much,” he explains.

As it turned out, Gellert had to do quite a bit of preliminary work

before actually getting down to mix each track. “Every song was a

little bit different,” he says. “There were so many

different performers, and people would move around the stage. I mixed

54 songs altogether, and after mixing the 20th song, you’d think I

could say, ‘Okay, I know what’s coming.’ But there was

always some technical thing I had to spend time with. On ‘The

Last Waltz Suite,’ I had to find the right performances by

A/B’ing with the record to make sure it was the right take. It wasn’t

straightforward, but that was the process and was expected by

everybody.”

Not surprisingly, Gellert had to make adjustments for different

players on the same instruments. For example, Richard Manuel’s grand

piano sounded very different when Dr. John sat down for the New Orleans

funk of “Such a Night.”

“I found that when Levon [Helm] was singing and playing, the

drums sounded very different from when someone else was singing,”

adds Gellert. “It’s a natural physical thing — when he’s

singing, he plays differently. The horns were also a little difficult

to bring out.”

Gellert and Robertson quickly established a routine. “I’d mix

all day, and he would come in toward the end of the day and we’d listen

and tweak the mix, maybe an hour, maybe two, and then it was

done,” explains Gellert. “It was the optimal way to do it.

I got it sounding the way he wanted to hear it — I learned that

pretty quickly — and then he’d make little fixes here and there,

just updating the mixes.”

For the stereo mix, Gellert and Robertson opted for a wide stereo

soundscape. “For the live concert, the premise was to make you

feel like you’re a little too close to the stage, in the first row, so

the stage is really wide, with the piano way to the left, Robbie’s

guitar way to the right,” explains Gellert. “That was the

idea: To make it really wide and to have the ambience of the arena come

from behind. I was very happy with it. With ‘The Last Waltz

Suite,’ I made it as wide as possible and I played more with all

of the available stereo fields, not just the left/right front but, for

example, the left front and right rear, as well. I mixed the extra

tracks after I mixed the rest of the stuff, so I had an idea of what I

wanted it to sound like. It was fun hearing tracks that, unless you’d

been at the concert, you wouldn’t have heard before.”

The surround mixes for the DVD-Audio release were addressed on a

case-by-case basis. “Some were similar, some were quite

different,” says Gellert. “On some of them, I did a

surround mix for the DVD movie and the film and then tweaked it a

little bit differently for the DVD-Audio. It needed to be a bit

different, because you’re not looking at the movie.”

Once Gellert completed the mixes for the film and video releases,

they went over to Ted Hall at Pacific Ocean Post. “I was there

listening to stuff; both Robbie and I went there now and then,”

says Gellert, “but Ted did such a fantastic job. He had all the

elements — the original dialog and all that — and he had

the same nightmare I had of finding the right things and making sure

that it’s appropriate and correct and the best it can be at this

point.”