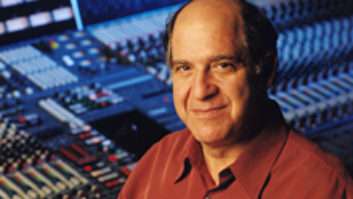

After 40 years in film sound — half of those working at

Manhattan’s premier post-production house, Sound One — Lee

Dichter has earned his reputation as the Dean of New York Re-Recording

Mixers. Dichter has seen the business go from mono to stereo to 5.1;

from small, hardwired custom consoles to the impressive Neve DFC he

works on today; and from optical film to Pro Tools. Along the way, he’s

amassed a staggering list of credits in television, documentaries, and

both independent and big-budget feature films — more than 130 in

all. He is known far and wide for his expert attention to film dialog,

which is why he has been tapped so often to work with directors who

care deeply about such matters: He’s done 17 films with Woody Allen

(every film since Hannah and Her Sisters, except for Curse of

the Jade Scorpion), three with the Coen Brothers (Miller’s

Crossing, Barton Fink and The Hudsucker Proxy), a pair with

Robert Altman (Short Cuts, Pret-a-Porter), a few with Barry

Sonnenfeld (Get Shorty, Men in Black, Big Trouble), and

countless others with such talented directors as Robert Benton, Mike

Nichols, Nora Ephron, Lasse Halstrom, Bob Fosse, Francis Coppola, Brian

De Palma, M. Night Shyamalan, Frank Oz and Tim Burton, to name just a

few. He’s just as comfortable working on big films like Signs and

Sleepy Hollow as he is with subtle, character-driven shows like

HBO’s powerful Wit. And Dichter has never stopped working on

documentaries: He’s plied his craft on such acclaimed films as

Harlan County USA, The Times of Harvey Milk, The Atomic Café,

The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg, Wild Man Blues and a host of

Ken Burns’ films and series, including Baseball, The Civil War,

Jazz and Mark Twain. When we spoke in late June, Dichter had

recently completed Woody Allen’s latest, Anything Else, and was

busy working on Angels in America, directed by Mike Nichols for

HBO.

A New Yorker through and through, Dichter was born into the

business. His maternal grandfather, Joseph Seiden, had been involved in

the theater in his native Hungary and then, after immigrating to New

York, became a producer of silent Yiddish films in the ’20s. Dichter’s

father, Murray, was an electrical engineer. He eventually went into the

family business, doing sound for Yiddish films in the ’30s and ’40s

(including a Yiddish King Lear!). “Then they started

realizing that, to get a wider audience, they had to go to

English,” Lee says, “so the films switched over to English

with a Yiddish accent.” Eventually, Murray Dichter broke away

and, in the late ’40s, started his own company, Dichter Sound Studios.

The business was focused on commercials for that upstart medium known

as television. “I used to hang out there on weekends,” Lee

remembers, “and I found it very interesting and exciting.”

Murray Dichter also did sound work on a documentary series for CBS

called Eye on New York.

Lee spent a year in college at Case Tech (now Case Western Reserve),

but “I didn’t really connect with it,” he says; instead,

beginning in 1963 when he was 19, he went to work with his father in

the sound business. Our interview picks up the story here.

I notice that in the IMDB [Internet Movie Database —

imdb.com] entry under your name, they don’t list any credits for you

until 1972. What kind of work did you do between 1964 and 1972?

I did a variety of different things for the company. He was a

wonderful artist and a great technician. Eventually, in 1964, my father

joined John Arvonio in a company called Photomag, which, like my

father’s, also specialized in commercials and short films. When I

joined up, I was doing one-to-one transfers, which led to equalized

copies. Slowly, they let me start mixing some easy commercials —

three or four tracks: narration, music, a couple of effects. And from

that, I started getting into some documentaries. The independent film

community was always looking for younger mixers, rather than people in

their 40s or 50s.

Or who would charge a lot of money.

Well, that too. But my reputation started growing from that.

Here’s the key. I learned how to mix on TV commercials, where every

word and every syllable was so important, because they only had 30

seconds or a minute to get their message across, and if you couldn’t

hear or understand a single word, you were gone. I found out

early on that the producer would say, “Lower the music, I can’t

hear that word.” And sometimes I’d say, “Well, let me work

on the word. Let me equalize that word differently so it rises in the

mix, and then we don’t have to lower the music.” So working with

different techniques with equalization and compression, I learned how

to handle dialog very well, and I learned techniques that I could use

later on with documentaries to really enhance what was on the

track.

I’m familiar with tools that big recording studios were using for

that during that era: 1176s and LA-2As…

I don’t even know what those are. I never really got that much into

the technical end. All of this equipment would come in, and I’d just

say, “What can I do with this? How can I use this to improve the

sound?”

What would you use for equalization?

I don’t think it even had a name. It was built into the console,

which was custom-made. It was the coolest thing, though. It had nine

little toggle switches sticking up in a row, and you could just

slip-slide them so you’d actually get a sort of graphic readout by

seeing which way the toggle switches moved to what kind of equalization

you were putting in the track. I had compression, too, but it wasn’t

sophisticated the way it is today. My father also built a combination

compressor and de-esser, which was very cool.

You say you’re not technical, yet all of this work involves

minute work: to go in and EQ certain words, and de-ess

others…

Well, when I say “technical,” I mean I don’t know the

names and the numbers. For years, a friend of mine was talking always

about “Cat 43.” I didn’t know what the hell that meant.

Then I found out it meant “catalog number 43 Dolby noise

suppressor.” I could never remember all of the numbers. I just

wanted to know what the piece of gear could do for me.

So much of what you do as a re-recording mixer is dependent on

the quality of the work of the original location recordist. What has

your relationship with those engineers been like?

Unfortunately, there’s always been something of a disconnect with

location recordists through the chain of mixing. Once their work is

done, we rarely hear from them. Occasionally, the location recordists

might try to get some input from us in advance, but it’s unusual when

that happens.

When you work on a documentary, is it significantly different

from working on a feature film in terms of the actual requirements of

the job?

Not really. The main thing is the budget. You don’t want to make

compromises, of course, but you have to go as fast as you can. With

documentaries, you’re usually limited to the production track; you’re

not going to do any looping. But you use the tools you have as best you

can.

At the same time, though, there’s usually a lot less material to mix

in a documentary. There aren’t going to be seven dialog tracks; it’s

more like three or four. Most of those early documentaries I did in a

day or a day-and-a-half. Harlan County was the first one where

it went more than two or three days. It was a five-day mix, and we even

had overtime in there. These documentaries are always a labor of love

for the filmmakers and for me. They’re working on them two or three

years, so you want to make it as good as you can without breaking their

budgets.

When you started doing bigger feature films in the early ’80s

— The Verdict, Sophie’s Choice, Star 80 — did the

requirements of the job change or the time you were given?

Definitely the time expanded, since they were more complicated.

So all those were done in New York?

Well, finished here. They might be shot all over. Usually what

dictates whether it’s finished here is where the director lives.

Where did you do most of your work back then?

Back in 1983, I joined Sound One. The first feature I mixed there

was Star 80. From then on, I was basically mixing features and

documentaries.

What sort of equipment did they have at Sound One in that

era?

They had a new mixing studio with a Neve console, and then they had

an older console in another room, which doubled as a Foley stage. I’m

not sure of the model number, but I think it was a music Neve with 48

ins and six outs. Up until then, I hadn’t mixed a film in stereo.

Photomag had only mono equipment. In fact, Star 80 was mono. My

first stereo film was Beat Street, which was a break-dance

film.

You also did Cotton Club with Coppola around that time.

On Cotton Club, we didn’t do the finish. We did about six or

eight weeks of premixing, and then they took it out to San Francisco

where Coppola lived. But the editing crew and the picture editor lived

here.

It seems that the way the profession has evolved over the past

several years is that, more and more, there are sound design teams that

are out there recording every type of civil war musket ever invented,

or 10 kinds of rainstorms, or 20 different makes of cars crashing.

There’s this obsessive hunt for verisimilitude in sound. At the same

time, there’s been a closer alliance between sound designers and

re-recording mixers. When did that trend really start to kick

in?

Of course, there have always been people who wanted to get

the most realistic sound for the films they were working on. But I

think that for what you’re talking about, the real beginning was

Apocalypse Now [1979]. Certainly, there were big sound jobs

before that, but that was the film where they really let the sound crew

loose. I have friends who worked on that film. The post-production was

something like nine months or a year, which was unheard of. And the

reason it went that long is Coppola was constantly recutting. But he

could do that because it was his movie; he was the producer. If the

director is working for the studio, you’re not going to get that.

When I started mixing features, it was usually a two- to four-week

mixing schedule. Sometimes, an extra week was added for more

complicated films. I remember when I worked on Star 80: After

six-and-a-half or seven weeks, we still weren’t finished. I was very

upset about it. My father had died the previous month. I went over to

[director] Bob Fosse, and I said, “Bob, I’ve been upset about my

father, and I really feel that part of the reason why we’re not

finished is because I’m going too slow.” And he said to me,

“Lee, you know the film Sweet Charity? We mixed 17

weeks…and it’s still not right. [Laughs] So don’t worry. We’ll

get some extra time and finish the picture.” And we did. But like

Coppola, he had the power to make it go longer.

Getting back to Apocalypse, what happened was he gave his

guys the green light to really go investigate all of the different

sound techniques and let them experiment. And they mixed it in 6-track,

magnetic 70 millimeter. So that was the beginning of this new era of

sound design.

Now there are a lot of California mixers who have created their own

niche and do a lot of recording themselves, too. And that’s great,

because they can follow the picture from beginning to end. But the way

I’ve always worked is I come on pretty near the end. I’m not recording

effects.

You started working with Woody Allen onHannah and Her

Sistersin 1986. What was he looking for sonically? Obviously,

his films are always dialog-driven. I would imagine he wants to hear

every word clearly, unless it’s for some effect.

That’s right. Well, he’s the writer, too, so, obviously, the words

are very important to him, as they are to me. With his films, you know

that the soundtrack is going to consist basically of the production

track and not much else. He lets us use very little added sound; only

when necessary, only when we have to. And then there’s the

music.

And you know what that’s going to be like, most likely some mono

jazz or pop track from the ’30s or ’40s.

Pretty much. And if you look at his films, you’ll see that sometimes

he’ll do a montage that’s all music and he’ll drop the location sound

altogether.

Is he very hands-on with the sound?

No. He’s not in the studio that often. A lot of directors love the

process of film mixing, and some directors would rather you just mixed

it yourself with the sound crew and the picture editor, and then he’ll

come in for playback and make some corrections and then come back three

days later for another reel. Woody is that way. He usually wants us to

copy the scratch mix. So we usually don’t try anything too new [in the

final]. And since he doesn’t use sound effects, it’s very easy to

follow that format because, basically, I’m working on maximizing the

dialog and constantly choosing filters and equalization to accomplish

that.

He likes the dialog in the forefront at all times and wants nothing

competing with it. And he doesn’t use ADR.

A lot of actors and directors hate looping.

That’s right. It happens all of the time that the line that’s looped

is not looped well. Usually, it’s the performance: The voice pitch

might be different, the timbre, the volume. The actor might be in the

wrong key with the wrong emotion. It’s a tough situation. The actors

usually don’t want to be there. Often, it’s months after they shot the

scene, there’s the anxiety of getting the performance correct, and then

the second anxiety of getting it in sync. Some actors have a wonderful

ear and a good attitude and they’re very good at it.

All we want, as mixers, is a fighting chance. Now, of course, we

have more tools to match things. Now we can get into pitch change. We

can’t change the push, but we can change the pitch.

Obviously, you become intimately involved with every film you

work on. Can you tell if a film is bad?

Sometimes. But what I learned to do way back, in my early years, is

separate my feelings about what’s on the screen and my work. If I’m not

really into the film, I never let it affect my work. I still have to do

the best job that I can. I focus on the process and make sure that my

input into the film is helpful and makes it better. The process

of mixing gives me so much joy. I get great satisfaction being

emotionally involved with the film, trying to bring it all together and

making the director happy.

Do you find that there’s great variety in how involved directors

are with sound?

Oh yeah. It runs the gamut: Sound is very important to some and less

important to others. Either way, I still have to do what I do as well

as I can. It’s just a question of how much input you get back from

them.

Where do the Coen Brothers fall in that regard? I know you

didMiller’s CrossingandBarton

Fink…

The Coen Brothers are the rare writer/directors who actually write

sound montages into the screenplay.

So you’ll look at the script of Barton Fink and it will actually

read, “We hear the sound of the wallpaper peeling of the

wall”?

Yes. With Barton Fink, the sound was so important to the

overall feeling of the film. The footsteps and the buzzing and the

wallpaper coming off of the wall, all that was written in and then they

shoot it with that in mind. More typical in a screenplay is it’ll just

say something general like, “You hear the sound of the birds in

the morning.” But the Coens get into some very specific things;

it’s part of their overall cinema vocabulary. It’s fantastic.

There’s a part near the end of Star 80 where there are all of

these camera clicks. They’re taking still shots of Dorothy Stratten,

and the sound of the camera shutter was composed of four different

elements, and then Fosse had us move the elements around to different

positions — we’re talking a half-frame, quarter-frame — to

get just the right sound he wanted. He was one of the few directors I

know who was involved in every aspect of the soundtrack.

Have Pro Tools and other digital systems made your job

easier?

Yes. There’s more accessibility to different sounds, and that opens

up the palette. You can access many things more quickly, almost as you

can think. It opens up more avenues of experimentation and creativity.

I remember before computerized mixing, the director might say,

“That sounded great: that whole sequence you did with the sirens

and the water and the car-by. I just want a little more on that

line of dialog.” So I’d have to try to re-create it step by step.

You’d try to remember exactly how you did each element, and then you’d

raise the dialog 2 dB. And usually some stuff wouldn’t come back. You’d

get it close. Now, it truly is repeatable. So by having more control,

the sound track is better.

The double-edged sword, though, is that because there are so many

possibilities, there’s a tendency to futz with things a little longer,

maybe go overboard trying different things. You have to exercise some

self-control to not work on it endlessly, because now you can.

That’s absolutely true. Like I said earlier, when I worked on

documentaries, you would have serious time constraints. Now, the time

has expanded, although, obviously, there are still constraints. And the

sound is so much more complex that it takes you six or eight weeks now.

A big movie — a sound-driven movie — can go 10 or 12 weeks,

and you might be running two stages sometimes. It’s mind-boggling

what’s going on, because of the amount of information coming in, the

choices, the different levels and layers, and now, by having the 5.1,

it’s that much more complicated. It’s exponential.

Are you enjoying 5.1?

I love it. It really has opened up the soundstage, and you can

really heighten the impact of certain scenes by having so much dynamic

range and having speakers that totally envelop you.

Somehow, I can’t see Woody Allen embracing 5.1.

[Laughs] No. Here’s a Woody Allen story. Up until some time in the

’80s, Woody’s films were always released in mono. By the time I began

working with him, we were starting to find out that playing a mono

optical on a Dolby pickup head in the theaters was degrading the sound

even more than it would normally, so we finally convinced him to start

mixing his films in the Dolby format so we could match the industry

standard, as far as the release was concerned. I think it was [the

film] September in 1987. We were pushing for years to try to

change him over, but he had his screening room set up for mono. So we

had to get Dolby involved to help push this along and help to entice

him to switch over. He finally agreed.

So there we were. We were sitting there knowing we were going to

release September in the Dolby format: left, center, right and

mono surround. The opening-credit music came on and it was in stereo,

and I had the pan pot wide open, and he says, “You know what,

Lee, that sounds interesting, but it’s a little too wide. Can you pull

it in a little?” So we went back and brought it in a little.

“Can you pull it in a little more?” And this went on and on

until it was finally dead center and he said, “I like that. Do

that for the whole movie.” I said “Woody, that’s

mono.” He said, “No wonder it sounds so good!”

[Laughs]

Lee Dichter Selected Credits

Blair Jackson is the senior editor of Mix.

A Bronx Tale (1993)

Carlito’s Way (1993)

Celebrity (1998)

Changing Lanes (2002)

Cradle Will Rock (1999)

Deconstructing Harry (1997)

The Devil’s Own (1997)

Far and Away (1992)

The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)

The Hours (2002)

“Jazz” (2001)

Just Cause (1995)

Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery

(1997)

The Mambo Kings (1992)

Michael (1996)

Mighty Aphrodite (1995)

Primary Colors (1998)

The Score (2001)

The Shipping News (2001)

Small Time Crooks (2000)

Snake Eyes (1998)

The Birdcage (1996)

What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (1993)