Much like a popular couple breaking up, the extremely dynamicalternative metal band, Living Colour, which officially disbanded in1995, was constantly queried about reuniting. Anywhere formerbandmembers went while pursuing individual ventures, fans, music-biztypes and fellow musicians asked the eternal question: “When isLiving Colour getting back together?” Even Mick Jagger —who featured them as an opening act on mid-’80s Stones tours, producedtheir demo and coordinated a subsequent record deal — tolddrummer Will Calhoun, “They needed to regroup.”Overwhelmingly, the band’s past achievements — garnering amulti-Platinum CD, two Grammys and two MTV Video Music Awards whilemaintaining an intensely loyal, global fan base — overshadowedtheir subsequent endeavors.

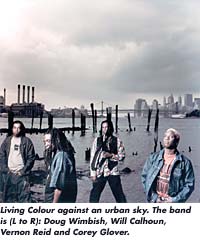

Still, from the perspective of the bandmembers — guitaristVernon Reid, vocalist Corey Glover, bassist Doug Wimbish and Calhoun— there were lingering issues concerning their generalfrustration with the music industry and the dissolution of unity withinthe group. Was there a real desire to be a full working band again?“It was kind of like, ‘Well, is there anythingthere’?” Reid explains from his home studio on StatenIsland, N.Y. “There’s a lot of affection for the people andhistory, obviously [being the first rock band of color to make animpact since the heralded days of Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone and Santana].But in my mind, you could always say, ‘No, no, no and hellno!’ Then, one day I just said yes.”

Living Color first reunited in December 2000 at CBGB’s in New York,the landmark venue where the quartet first crafted their sound and wasdiscovered. Calhoun and Wimbish were there doing a drum ‘n’ bass sideproject called Headfake, with Glover sporadically helping out. WhenReid accepted their invitation to sit in, the show billed“Headfake and Surprise Musical Guest” turned into a full-onreunion jam. Riding the crest of ecstatic fan response, they continuedplaying sold-out club dates across the States and made festivalappearances in Europe and South America. Talk of returning to thestudio to record a new CD ensued, but the band couldn’t seem to agreeon direction, methodology and, foremost, a definitive reason to devotethe time and effort. In the midst of their disparity, the 9/11 tragedyoccurred.

“It’s not our reason, either,” declares Reid, who couldpreviously see the World Trade Center towers clearly from his house.“But what it is, is that we were able to start thinking abouteach other in a different light and talk about issues in other ways.Also, it made us look at the music we did before differently.Ironically, ‘A ? of When’ was written before 9/11, eventhough it seems right on top of it.” Consequently, Living Colourfound that many of their recently penned songs had other meanings and athird of the songs on their reunion CD, Collideoscope, arerelated to the catastrophic event.

For the process of forging lyrics and sonic elements, the bandinitially headed to Long View Farms in North Brookfield, Mass., duringthe spring of 2002. They’d cut the album Pride there, the CDprior to Living Colour’s breaking up, and Reid describes its owner,Bonnie Milner, as a “wonderful ally to the band.”

However, when the members were pursuing various solo ventures,Wimbish also formed an allegiance with engineer/drummer/drum programmerChris Weinland, who owns and operates Tree House Studios in Storrs,Conn., midway between Boston and New York. This studio, which islocated in a converted garage/barn adjacent to a state park, becamecentral to the recording of Living Colour’s latest throughout the fallof 2002 and into the spring of 2003. The isolated natural setting ofWeinland’s studio, where cell phones are out of range, provided thenecessary solitude that the band needed to write and try out songs.Also, Reid could crank up his guitar and equipment to his heart’scontent without being concerned about any neighbors.

Reid, Wimbish, Glover and Calhoun worked together about 80 percentof the time at Tree House, penning lyrics and jamming. Added guitarsand reworked drum parts were done individually, and often the wholeband wouldn’t make the trek. “There were torrential snow stormsevery Friday when they would come,” the studio owner/engineerrecalled. “And sometimes, it would take up to four hours to gethere from New York. Normally, it takes a little over two hours and wegot over 100 inches of snow last winter. I was laughing a couple ofweeks ago with Doug about that and how they ended up getting so muchstuff done here, ’cause what else are you going do when there’s threefeet of snow out and it’s below zero?” The group also didsessions at Wimbish’s Novasound Studios in Connecticut, On-U-SoundStudios in London, Sound Studios in Los Angeles and The Cutting Room inNew York.

Weinland comments about the band’s creative process forCollideoscope: “They’d been apart for some time and theyreally needed to get their heads back in it. So there was a certainamount of just regrouping, and they would come up for four or five daysat a time. A lot of stuff would get written, which we would edit. Thenthey would decide what they liked and we would retrack a lot of stufflater on. The arrangements, I guess, would be backward from what youwould expect when you’re writing an album. Things would be played, thenarranged and then replayed. As late as March and April [2003], we werestill doing vocal tracks. But it was really interesting to see how theyworked and developed tunes. And, obviously, the musicianship was aboutas good as you’re ever going to see from a rock ‘n’ rollband.”

All tracking for their reunion CD done at Tree House Studios wasrecorded on Pro Tools through such supporting gear as modules from anold Neve broadcast console (believed to be Sonic Youth’s old board),API preamps, Apogee converters and various vintage mics — mostlyNeumanns. Weinland stresses that he wanted to keep the signal path asclear as possible, and the combination of preamps and mics used forthat application worked perfectly.

Just the same, Reid was very comfortable and stayed with Weiland’sfamily for extended periods during the creation ofCollideoscope. “[Weinland] was a big fan of the band, hiswife is a graphic designer and their son is a great kid,” hecomments. “So it was a nice environment to be around while wewere doing the live stuff. Also, we had a lot of help from differentengineers working as a team, such as Michael Ryan, Dave Shuman and FranFlannery, who did a lot of editing.”

Musically, there was plenty of high-octane jamming at the sessions,with a noticeable strong dose of funk injected. Reid believes thecurrent sound harkens back to the exploratory times at CBGBs and theMudd Club. Reid and Wimbush used Reason software for composing andCalhoun programmed some beats. Loops and samples have always been animportant ingredient in Living Colour’s music. However, it hasdeveloped way beyond their initial forays.

“From the time we did Vivid, we’ve worked with samplesand things like that,” Reid states, “and now we’re startingto integrate that more into what we are doing live. It’s an interestingchallenge, and now Doug and I both have laptops onstage. We play live,but we also incorporate all kinds of different elements andwhat-have-you. Of course, I also have a full Moogerfooger pedal linefor whooping, blarings and things like that, along with virtualones.”

In contrast to the elongated periods of songwriting and tracking,mixing for Collideoscope went fairly quickly. “The mixingwas done by our live engineer, Andy Stackpole,” Reid says,“one of those rare people who has that other skill set.”Stackpole, a 10-year veteran who’s worked with Bad Brains, the BeastieBoys, Busta Rhymes and others, became Living Colour’s front-of-houseengineer two years ago. He actually didn’t feel that the transitionfrom front of house to being a studio mixer was that difficult, because“if you mess up, you can go back and do it again.” However,he quickly found that the pressure to get things done made mixing farmore intense.

After a week of overdubbing, editing and going through everything,he had 11 days to complete 15 tracks. “I really wish I’d had moretime,” Stackpole says from his home in Norwich, Conn. “Itwas mix, mix, mix. I didn’t really have any time to get away and listento it in my own environment.” At Soundtracks in New York, theengineer, with Reid on hand and the bandmembers occasionally droppingby, mixed Living Colour’s release on a vintage Neve board. And althoughit was his first time handling a major project, he had one bigadvantage: “I had started working with them as they weredeveloping songs and playing them live to see what worked and whatdidn’t.”

Unequivocally, the band and Reid were happy with the engineer’sefforts and are pleased with the album in general. The band feels thestrongest it’s been for a long time. “Now that we’ve donethis,” Reid states, “tomorrow is the question. In fact,Corey and I have already started talking about the next record andthere’s some very interesting aspects we’re thinking about. In a way,the band does pick up where it left off. So it’ll be interesting to seehow it all evolves.”