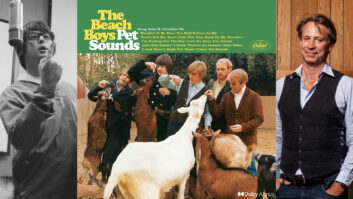

Martin Pilchner looks like a scientist and an international man of mystery, at the same time. He is equally comfortable with an acoustic guitar playing classic rock songs on a small club stage as he is wearing a hardhat on a construction site. He is a professor at Harris Institute in Toronto and he is one of the world’s leading studio designers. He knows math, and he knows a few jokes.

A Saskatchewan native, he first learned accordion, then guitar, all the while running around the family construction business. He originally studied electronics locally and took a job with the phone company in the computer communications group before leaving to go on tour with a band. He got bit by the recording/production bug, eventually converting the tour bus to a mobile rig, and hasn’t looked back.

He went back to recording school in Toronto, and in his second year he designed and built the campus studio, teaching there after graduation. In 1986, he formed Pilchner Associates, then went back to school for an architecture degree, designing low-budget rooms along the way. While designing a room at Fanshawe College, he met Rick Schoustal, an engineering/production student with a background in business who handled the installation. After Schoustal moved to Toronto, the two continued to work together, with one of their first projects being a studio for Jeff Healey. In 1994, they incorporated, expanding to Pilchner-Schoustal International Inc. in 1998.

Let’s start with Canada. What’s your view on the current music and recording scene in general?

I think it is difficult to generalize, as it is driven by so many local factors. Canada as a national market is analogous to the U.S. with its dramatic regional differences. A number of years ago many studios were lost by market conditions, and in many cases it created a void, which is now being filled by new studios. This doesn’t happen without some level of available work. A commercial “for hire” studio is certainly not as common as in previous decades, but it is still necessary, and when positioned correctly can thrive. There has also been a large growth of personal studios of very high caliber. These are being developed for people who inherently need them and have cornered a particular market niche. They cover all uses from post and music composition to recording artists. We cannot lose sight of the fact that there is growing demand for media content regardless of the ability to monetize it by the industry.

The press here tends to focus on Vancouver and Toronto.

In many ways it is the same as saying the press tends to focus on Los Angeles and New York. There is a lot of creative production work that originates in the Maritimes and the Prairies, but success is always measured by popularity in major centers, and to be fair, Quebec is a major market unto itself.

You have talked before about distancing yourself from tried-and-true studio design methods and embracing the modern. Yet you also are a scientist who understands the laws of physics and the capabilities of materials/construction.

I would not say we have rejected the tried-and-true studio design methods; on the contrary, physics is our language. The acoustics and the quantifiable performance has always been our hallmark. The performance must be a given. Unfortunately that is where vernacular design approaches stop. I think this is a mistake; this is where the real design begins. Years of acoustic rationalism have led to cold and austere environments where the technical dogma actually interferes with the underlying purpose of the studio. This is namely the imaging of art, or the changing of a performance into a product. A studio must carefully balance the technical and the creative to be successful. The technician and the artist must both be freely at ease in the environment. A studio should be an inspiring and not intimidating space.

Control Room B at Revolution Recording in Toronto, a Pilchner-Schoustal-designed facility.

What is your philosophy regarding the intersection, or integration, of Architecture and Acoustics?

Throughout history, acoustics has been an integral part of architecture. In modern society it seems to be only valued in specific applications such as studios and performance spaces. Designers need to spend more time “seeing” with their ears. Research in multi-modal perception is going a long way to help people realize how all of our senses work together to form our experience of space, and sound is certainly a big part of that.

What is the first thing you would say to an engineer/producer who comes to you asking for advice on how they can improve their high-end personal studio?

The first thing would be to come to an understanding of the fundamental truth of what they are trying to achieve. Embrace the constituent and let go of the transitory. This means stripping away all the urban myth and vernacular studio opinion to arrive at an honest understanding of what is needed and possible. This becomes the departure point for moving ahead.

Working with Low End. Is it the most challenging aspect of studio design?

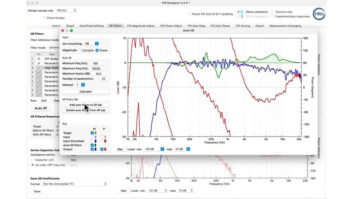

Working with small space acoustics such as studios, the low-frequency uniformity is always a factor. Balancing the force and resonant response of the room and electro-acoustic systems seems best handled with a combination of prediction and experience. However, I would say the most challenging aspect of studio design is balancing the client’s ambition with their budget.

You have made a commitment to teaching at Harris Institute for many years now. What does the experience in the classroom bring to your professional life?

I have a passion for studio design—what could be better than to share that with captive audiences who are eager to learn? I find that having to explain things to others brings you to a greater understanding of the subject, as well. It is also gratifying to see your former students find their own success.

Clients and former students all mention your vast intelligence and your quick, sharp sense of humor. Is it important to have both in your field?

I’m not sure, but if you truly enjoy your work, I think you should also have fun doing it! It is good to have a sense of humor, but at first it takes the client awhile to understand we may be funny but at the same time are deadly serious about our work.