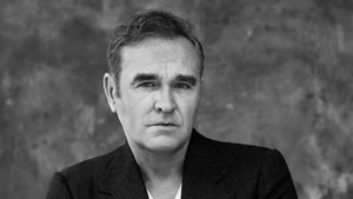

Joe Chiccarelli, pictured here at EastWest Recording Studios in Hollywood working on the upcoming Jason Mraz record. Engineer Steve Churchyard has his back to the camera.

Photo: Ana Gibert

[Ed. Note: Mix magazine senior editor Blair Jackson continues his conversation with producer/engineer Joe Chiccarelli about working with Jason Mraz, My Morning Jacket, and female artists, and more experiences from his career.]

When you were working on Jason’s album, would you do multiple takes of a song on a given day?

Yes, I’d say we took an afternoon on each song—maybe four to six hours getting a basic track on each. We actually tracked something like 23 or 24 songs, plus on several of them we took more than one crack at it. We did it once and came up with something that we liked at the moment but then, in reflection, it wasn’t quite what Jason was looking for: “This is too ordinary,” or “This is too bombastic,” or whatever wasn’t quite right about it. In a couple of cases we went back and re-tracked things. Luckily, with an artist that’s successful, you have the budget and the time to do it properly, so you have the ability to, number one, hire great musicians—these are guys I’ve worked with a lot and they know they can give me honest feedback. They’re also really wonderful about taking direction, but at the same time they use that direction as a starting point to do their own thing. That’s what you always want as a producer. I deliberately try to be as vague as possible, to give a musician all the freedom in the world to interpret the thing his way, because I think that allows them ownership of the idea and that brings something more special to it. Jason loved working with them and working in this manner.

Jason Mraz listens to mixes in Tony Maserati’s studio

Photo: Ana Gibert

How was your experience working with My Morning Jacket on Evil Urges? I’ve come to really like that band. Jim James is amazing!

Talk about collaborative—I’ve never met a band that works so well together. They all love and respect Jim’s songwriting so much that the team spirit there is just fantastic. They’re really like a family. Some bands are very dysfunctional families, and they’re not; they’re very healthy. It was a wonderful experience.

Is there anything different about working with sensitive female artists? You’ve made great albums with people like Tori Amos, Natasha Bedingfield and Christina Perri.

Well, each one is different; you can’t generalize. Tori and I were like brother and sister; we got along so great. It was kind of silly times—we laughed through the whole session. But it’s always difficult with an artist who is very confessional with her songs. You have to be really sensitive and aware of that, especially when you’re doing vocals. Some singers have to dig deep in their past and dredge up that emotion to really give you that convincing performance, so you have to be sensitive to that and create an environment where people feel safe and willing to go there. It’s not just women, either. Guys can be the same way. They might express it differently.

Jim James is certainly digging deep…

Absolutely. Jim’s interested in not only how emotionally the stuff has to be right, but he’s got a really good sense of the sonics—he understands the reverbs and his textures, and when recording him he really works the reverb. It’s important he has the right reverb in his headphones to sing to, because he’ll play off it.

In the early ’80s you started doing a lot of mixing of albums you didn’t record or produce—Glenn Frey, Romeo Void, The Bangles, etc. Did that experience affect your engineering work at all?

Having a varied background always helps anybody, and the great thing about mixing stuff is you get to see how somebody else put their tracks together. I was fortunate back then that I was working with people like [producer] David Kahne, or more recently, Greg Wells—people who are really great record-makers. You learn things on every project you work on. The other thing you learn is to be sparse in your arrangements, to not leave a lot of decisions to mixing. I try to build the record as I go and not make it a mystery when you mix. The mixing process should be relatively easy. It should be about balances and priorities, and not about arrangement.

Have you ever gotten into a project and realized, “Uh-oh, this is not happening”?

Sure, we’ve all been there. [Laughs] When you’re first starting out, you’re anxious to do anything—you just want to be in the studio working on another record. You sometimes jump into things prematurely. Maybe the artist doesn’t have all the material together, or he isn’t clear on his direction. That’s a problem. A big part of your job as a producer is understanding the artist and what they’re trying to achieve and making sure they’re clear on that—that they’re not wishy-washy. When there’s a lot of ambivalence that makes it difficult. As a producer you need to take the time to sit with the artist and talk with them and make sure that they are clear about what they want to. The only times I feel I’ve failed is when the artist failed, in the sense that they weren’t sure what they wanted, or they changed their mind mid-stream, or they as a band couldn’t agree. Being a producer is a service role. You’re working with them. It’s your job to execute what their vision is. Yes, you come to it with a picture of what you’d like to do and you have your own ideas, but ultimately it’s the artist who’s got to live and die by it. By the time the album comes out, you’re on to your next project; they’re out on the road playing these songs for months or years to come. So it’s worth the time and effort to try to get it right.