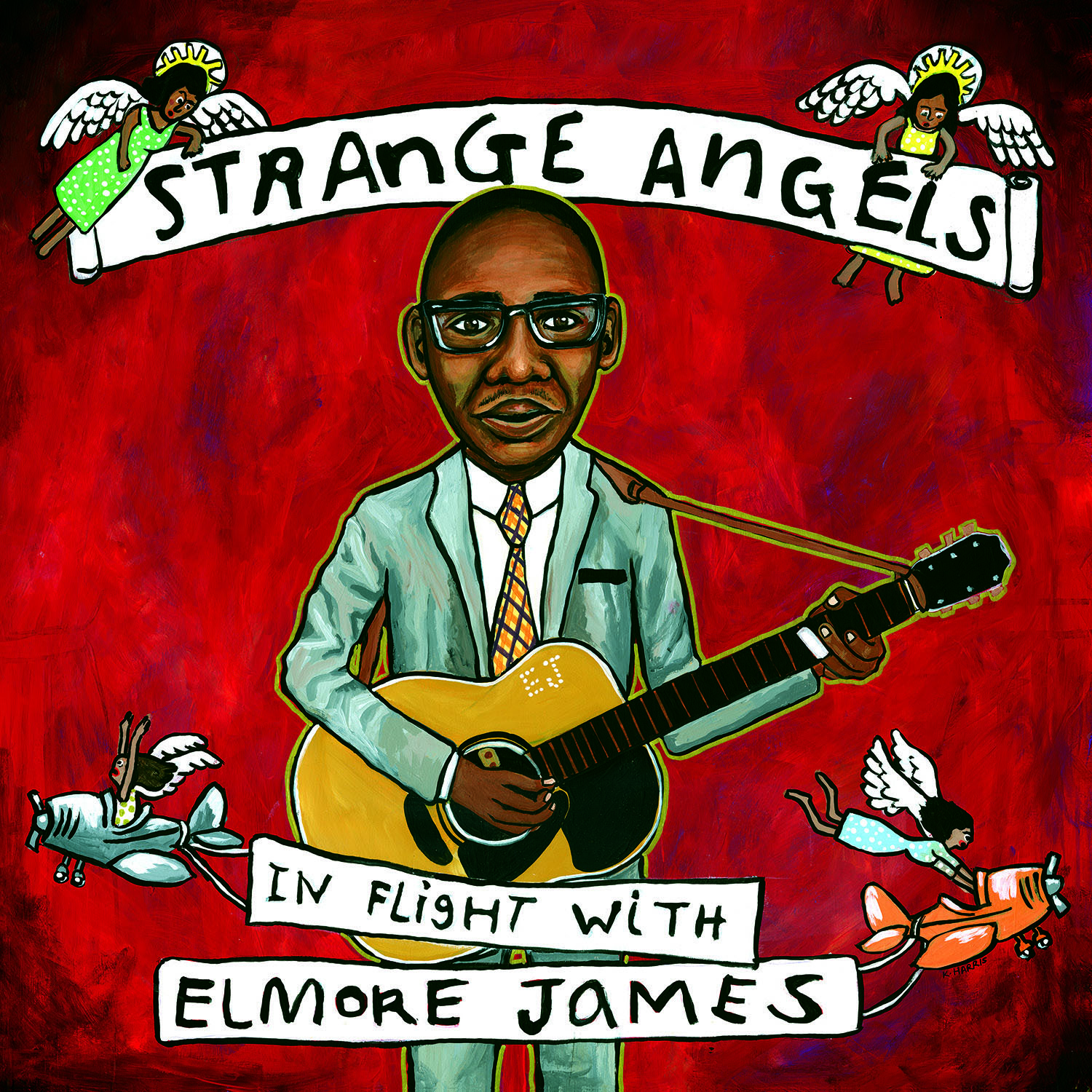

Brilliant material, famous names, great players, big heart: Strange Angels in Flight with Elmore James—released one day before what would have been James’ 100th birthday—has just about everything going for it. The album pays homage to the legendary blues slide guitarist with sisters Allison Moorer and Shelby Lynne harmonizing on the title track, Rodney Crowell swinging on “Shake Your Moneymaker,” Sir Tom Jones rocking “Done Somebody Wrong,” and so many more.

This benefit project—profits from Strange Angels help to support Musicares and the Edible Schoolyard NYC—was conceived by producer/drummer Marco Giovino. “Elmore has always been one of my favorite artists,” Giovino says. “I’ve always felt he deserved wider recognition for his writing, playing and singing. I selected the diverse group of artists in order to portray all of Elmore’s talents.”

Giovino, who has appeared on albums by Robert Plant, Norah Jones and others, enlisted a platoon of engineers as well as musicians to re-interpret gems from James’ catalog. Tracks were recorded live in several studios, including Giovino’s Boston-area personal studio, which he calls Dagotown Recorders. There, engineer Sam Margolis recorded a few of the album tracks, as well as overdubs for several others.

“I think for everybody involved, there’s a level of excitement and energy that comes from playing in tribute to one of the greats,” Margolis observes. “And from the engineers’ standpoint, Marco made some decisions around the approach to the production that made our jobs exciting, as well.”

Giovino wanted all of the songs on the album to be performed as live as possible, and he chose studios particularly well-suited for that. He also made it known that, while he wasn’t trying to re-create the sound of old records, he very much liked the results of classic blues recording techniques. That meant placing distant mics and embracing bleed to some extent.

Giovino’s drum kit is the one element that appears on every song on the album. “In Marco’s studio, we used one drum overhead—an AEA R44C, their version of an older RCA ribbon—and that overhead is a lot of what you hear on the album,” Margolis notes. “But we also put up a Shure SM57 on snare top and two mics on kick, an Electro Voice RE20 on the beater side of the drum to get some of that nice attack, and then to get some of the funkier bass coming through on the back side of the drum, it was an AKG D12DR.”

Margolis also placed a pair of Golden Age Project R1 MK2s a couple of feet off of the ground and five feet away, pointed at the kit, to add even more boomy room to the tracks. “The approach was heavily reliant on dynamic mics and ribbons to get warmer sounds,” Margolis says.

“A lot of the overdubs we did were very subtle, but subtle with intent,” he continues. “We didn’t go into this knowing we would put a bass clarinet overdub on ‘Dark and Dreary’ [sung by Addi McDaniel], for example, but it’s the exact instrument that was needed.”

Another handful of songs were tracked in Nashville at Welcome to 1979 Studios by engineer Edsel Holden: “We did four artists all in one incredibly long day,” Holden says. “I was in the studio at 8:30. Keb Mo got there about 10:30. Rodney Crowell came next, then Jamey Johnson, then Warren Haynes. We went till 3:30 or 4 the next morning.”

Throughout the long day’s work, Holden learned to expect the unexpected. Crowell, for example, walked into the main tracking room and asked if he could sit on the floor without headphones rather than use the booth.

“I’m like, ‘Of course!’ I wouldn’t say no to Mr. Crowell, but that was a bit of a change-up,” Holden says. “I miked him with just an SM7, directly up on his face, to keep him as isolated as I could. Hats off to Gus [Berry, mix engineer] for making that work out. A live mic on the floor with a drummer in the room can be pretty tricky!”

All of the other lead artists were set up in the vocal booth with a Neumann U67 mic, while Giovino, slide guitarist Doug Lancio and bass player Victor Krauss were set up in the live room.

Guitar amps each took a 57 and an RCA 88, while Krauss’ bass was captured via his personal pickup system and a Beyer M49, “looking at his fingers but not the sound hole,” says Holden. “It was a crazy day and it went pretty quick. It was one of those days you wish for in the engineering world.”

“I think [a lot of artists were in town for a rehearsal for a Merle Haggard Tribute at Bridgestone Arena,” Giovino says. “Jamey Johnson was the instigator in getting Warren Haynes, Billy Gibbons and [harmonica player] Mickey Raphael to show up at the studio and play. He actually called Mickey around 12:30 a.m.—got him out of bed. It certainly was a fun and memorable night.”

At Flux Studios in New York, engineer Daniel Sanint recorded “Person to Person,” performed by Bettye Lavette and a band including guitarist Duke Levine, G.E. Smith on slide guitar, John Leventhal on baritone guitar, Charlie Giordano playing B3, Phil Butler on upright bass and Giovino on drums.

And in L.A., engineer/studio owner Clay Blair recorded another handful of songs in his studio, Boulevard Recording (in the facility formerly known as Producers Workshop). His sessions included the title track, as well as Chuck E. Weiss’ version of “Hawaiian Boogie” and Tom Jones’ cover of “Done Somebody Wrong.” The Jones track rocks with electric guitar by Rick Holstrom, Rudy Copeland on piano, Larry Taylor playing upright bass and slide guitar, and double drumming by Giovino and Jay Bellerose.

“Marco was accompanying Jay in a way,” Blair says. “They would just sit next to each other and play for an hour or two, and then Marco might swap snares or cymbals. I put different sets of mics on them to emphasize the different sounds of their kits and the way they play. Jay’s was more dark and Marco’s more rumbling.”

Jones sang live with the group, into a Neumann U48. “All of the singers were on a U48 except for the duet of Shelby and Allison,” Blair says. “On them I think I used a 67 and an 87.”

Early on in the project, Giovino decided that he wanted the songs to be mixed to mono. In the end, five tracks were mixed by Lorne Entress at Harmony Street Studios in Pomfret, Conn., while the other seven were handled at Nettlingham Audio (Portland, Ore.) by Gus Berry, who used his Pro Tools 12 rig, and a blend of outboard gear and plug-ins, to realize Giomino’s vision.

“Marco loves the enigma of mono recordings from those days [1951 to 1963, when James was recording], and the way things sound through far-away mics,” Berry says. “He loves how you can’t quite tell where some of the sounds were coming from—it becomes one big mystery instrument.”

Berry’s go-to gear on this project included the Shadow Hills Dual Vandergraph on drums: “Even though that’s a stereo compressor, it worked great on a mono source, and on the two-mix, I used the Charter Oak SCL1,” he says. “I also used the Crane Song HEDD, their AD/DA converter; it lightly shaves off some of the high end but it’s got a lot of low-mid oomph, and that helped on this material.

“Other than that, I used SoundToys EchoBoy for slapback, and pretty much every channel had the Slate virtual tape machine on it,” he concludes. “The songs that were cut in the pro studios were almost too clean for our purposes, so I used a lot of distortion and saturation when I was mixing from SoundToys Decapitator, and parallel compression from the UAD Fatso. Marco loves distortion and raunchy, dirty sounds, so I got to go hog wild with blowing things up. That was really fun.”