For anyone interested in starting or furthering a career in sound recording through formal education, there is no shortage of possibilities, from full-time enrollment at a dedicated school that focuses on the sound arts, through taking elective courses as part of a music, business or other college degree. But on the flip side, what opportunities are there for established audio professionals who would like to pass on their knowledge and experience to those on the path to a career in sound?

Leslie Ann Jones, a multi- Grammy Award-winning engineer and a pioneering woman in a male-dominated industry, started out at ABC Recording Studio in Los Angeles in 1975, and since 1997, has been director of music recording and scoring at Skywalker Sound. Jones is very selective about her teaching opportunities. One such rare appearance was an advanced recording clinic sponsored by Sennheiser and Neumann, and hosted by retailer Full Compass in Madison, WI in July. “I’ve had a very good relationship with Sennheiser for many years, so I was pleased they asked me,” she says.

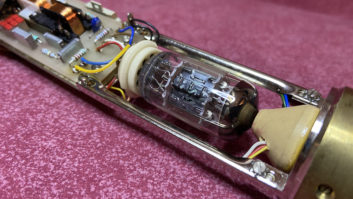

Bil VornDick in Belmont University’s Oceanway

Nashville Studio A control room As Jones points out, there were no such events when she was starting out. “We couldn’t go to workshops or watch people talk about microphones. It was a different era. But we got to work with a lot of different engineers and learn different techniques.”

With so many audio engineers working out of small project facilities, there are fewer opportunities to interact with other engineers, she points out, and there tends to be limited access to a wide variety of audio gear. “So you don’t have the opportunity to try new things or see what works,” she comments.

The only regular event that Jones is involved with is a performance camp for girls, which is held at the Institute for the Musical Arts in Massachusetts. “They added a recording track about four years ago, so I go every year and teach these young women, who are primarily instrumentalists and songwriters, something about recording and technology. I don’t expect any of them to become recording engineers, but I do hope they take away the ability to feel more comfortable around the technology and to respect the process of recording, both as an engineer or producer and as an artist.”

With that foundation, she adds, “It allows them to go to their local music store and buy Pro Tools or some other workstation and a microphone and at least know what to do with it, and what to expect out of it.”

Also in July, Jones taught a workshop at the Bay Area’s Ex’pression College for Digital Arts, where she is on the Recording Arts advisory board. “Their students don’t get much of an opportunity to learn classical microphone techniques,” she reveals. “Since I record a lot of that music, they asked me to come in and do that.”

Chris Mara (standing, left) offers instruction during a

Tape Camp at Welcome to 1979 studio. Bil VornDick, a Nashville-based engineer with a variety of industry awards on his shelf, attended Belmont University when he was starting out over 30 years ago, earning a BBA in Music Business. Over the years, in a desire to give back to the industry, he has lectured at colleges and other venues around the country, and is currently an adjunct professor at Belmont, where he teaches an advanced recording technique class of about a dozen students every Saturday during each semester.

“I’m very fortunate that I have Ocean Way Nashville as my classroom,” he laughs. Before he gets them, Belmont students have already learned the essentials of recording, starting out in the on-campus studios and Belmont-managed RCA Studios. “I know what they’ve learned, so then I add the finishing touches on a lot of different things, such as signal processing or mics, and which to use for which tone color. I spend a lot of time on acoustic instruments, because those are the big challenge.”

He continues, “I have them think outside the box. What I enjoy is seeing the light bulbs go on.”

It’s a two-way street, he acknowledges: “I actually wake up early on Saturdays because I’m looking forward to going to the class. It also keep me on my toes with all the new equipment, because you never know what the students are going to ask.”

The ultimate reward, he says, is hearing from his students after they graduate. “It’s the e-mails afterwards, once the students get into their career, or they want to meet for lunch and talk about career goals. That’s one of the more rewarding parts of it.”

The biggest challenge for students may be finding a job, believes VornDick. “Because there are so many schools, it’s hard for the students once they graduate. But they’re not looking at all the different venues where they could get jobs. They all want to be first engineers making hit records. They could get a really good gig doing audio at a big hotel chain, or with the U.S. government, the military, with a church, or something like that.”

Leslie Ann Jones in the control room

of the Skywalker Sound Scoring Stage It’s also hard for those experienced engineers who would like to get into teaching, he says. They may have a couple hundred albums to their credit, but colleges, especially at university level, typically demand that they also have a masters or even a doctorate. “Many of the guys that have gone through college and gotten their degrees, their bachelors, are shunned at universities. In the long run, I think, the students get more out of the person that has the experience and a long tenure in their art than a paper-trained professor.”

An independent engineer and producer for many years, going wherever the work took him, Chris Mara finally put down roots in 2008 and established an all-analog studio, Welcome to 1979, in Nashville. Mara also established Tape Camp, an analog recording workshop that has been held at his studio, in Minneapolis, MN and Cleveland, OH, and most recently at Stratosphere Studios in New York.

“It had always been something I wanted to do,” he says, noting, “There are always people who want to learn things, but they don’t want to enroll in a $20,000 recording school.”

Tape Camps are restricted to no more than 10 attendees, he says, and the curriculum depends entirely on what they would like to learn. “They might want to try using mid-side or a ribbon mic or punch-in on tape.”

He continues, “The people that come to these are just the best; they’re so inquisitive. It really rekindles my love for it. I know it sounds ‘cheeseball’ to say it, but I learn so much every time I do [the Camps]. I’ve incorporated things that we’ve tried on a whim into my everyday sessions.”

Mara’s past experiences with interns at his studio were less than satisfactory. “I feel a sense a frustration that not many people want a career as a recording engineer; they want it as a hobby. It’s hard for me to invest in that person. It’s been hard to find someone to mentor.”

That’s why Tape Camp works, he says: “There’s an admission fee, so I’m making a little money. I get to go somewhere for free, and my wife gets to travel with me. And they’re eighthour days instead of 20-hour days!”