Don’t call Shooter Jennings an outlaw.

The son of country legends Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter, raised on tour buses in the company of Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash and Kris Kristofferson, it seemed that he was destined for a career smashing the boundaries of country and rock in pursuit of his own musical truth.

Yet Jennings, an ’80s kid at heart, is less interested in the superficial trappings of the modern outlaw movement than its spirit of embracing honesty, however that may manifest. A musician since the age of 5, he left Nashville in his late teens for Los Angeles, releasing two EPs with his Southern rock band Stargunn before focusing on solo work.

Since 1996, Jennings has released eight studio albums and a mountain of live albums, singles and EPs. A hellraising rock and roller, he also spends time at home programming sequencers and crooning busted ballads; in his discography, traditional country records coexist with dystopian concept albums and disco collaborations—from his 2005 scorcher Put the ‘O’ Back in Country; to 2016’s Countach (For Giorgio), a synthy, vocoder-laden tribute to Italian electro-pioneer Giorgio Moroder; to 2018’s Shooter, a return to his rowdy country-rock roots, co-produced and co-written by longtime friend and collaborator Dave Cobb.

In recent years, Jennings has focused more on producing, collaborating with Jamey Johnson, Wanda Jackson and Billy Ray Cyrus, and helming albums by alt-country artists Jamie Wyatt, American Aquarium and Hellbound Glory.

Since coproducing Brandi Carlile’s landmark By the Way I Forgive You in 2018 with Cobb, Jennings has been immersed in wall-to-wall high-profile rock and country projects, producing Guns N’ Roses bassist Duff McKagan’s solo effort, Tenderness, and collaborating with Marilyn Manson on his 11th studio album, slated for release later this year.

Last year, Jennings, together with Carlile, produced Tanya Tucker’s 25th album, While I’m Livin’. The record—Tucker’s first in 17 years—has been celebrated as one of her finest, drawing comparisons to the late-career work of Cash and Kristofferson and earning Grammys for Best Country Album and Best Country Song and Americana Award nominations for Album of the Year, Song of the Year and Artist of the Year.

Mix sat down with Jennings to talk about evolving musical mindsets, funky vintage gear and the impact he hopes to make as an artist and producer.

How are you weathering sheltering in place?

I got lucky; I worked on a bunch of records last year, and they’ve all been coming out during this time. I was working on the Marilyn Manson record in January and February, finishing the mixing and the mastering, and then this thing hit. Then there was a record that Margo Price produced with my mom, Jessi Colter, that I’ve been mixing. Luckily, with my home rig I’ve been able to work the whole way through.

What’s your home studio setup like?

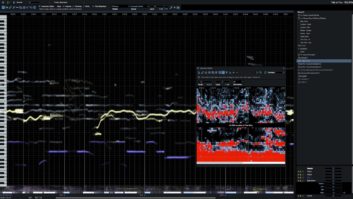

It’s pretty unique. I have a Pro Tools HD setup, and I’ve got a bunch of really cool outboard gear. I’m kind of eccentric in the sense that I like to pick up odd versions of things. For instance, everybody uses the UREI 1176 Rev F; I’ve got a Rev H, which is what ELO used in the early ’80s. And I’ve got an LA-2A and an Eventide H910, which is essential in my opinion.

I do it all in the box, but I have one of those little Artist Mix [control surfaces] that Avid makes, and then I’ve got a Lexicon 224, one of the original 1978 units that was actually Neil Young’s personal one. It has his notes on the back—settings and things—so that’s really fun.

I’ve got a bunch of great Spectra 1964 pre’s and a couple of dual Chandler TG2s.When we were mixing the Manson record, [engineer] Spike Stent turned me on to a piece of gear from Overstayer called the Dual Imperial Channel. It’s two channels and has a pre, limiter, EQ, it’s got lots of cool gain functions, and it’s all modular. I use that a lot when mixing to run things through, especially drums, like sends, when you want to keep the bite and the low end but you can kind of carve out EQs in a different way.

I have a Shadow Hills preamp, I’ve got the Chandler RS124 compressor and Focusrite Red preamp. And I just ordered a Binson Echorec 3, which I’m very excited about.

That’s my whole home rig. It’s really built for mixing. I record a lot of projects that I’ve done the basics for in my home studio and then take them somewhere to do live drums and things like that.

Where do you like to record?

I use three studios a lot. I use these two engineers all the time, David Spreng and Mark Rains.

There’s a studio in Echo Park called Station House. The Duff McKagan record, the White Buffalo record, the Jamie Wyatt record and the Hellbound Glory record were all recorded at Station House. And Mark engineered the Tanya Tucker record. I’ve recorded probably 20 records in that place.

The American Aquarium record was cut with David Spreng at Dave’s Room, which was Dave Bianca’s old studio. David Spreng’s studio is deep in the Valley; it’s a little larger, so it’s got more hang room and isolation. It’s got tons of amps and gear and an amazing rack, everything is pre-wired, it’s all top-of-the-line.

Then, Sunset Sound, if the budget is there, it’s my preferred place. I did Tanya’s record there and a record for The Mastersons there in the Purple Rain room.

Looking back, when did you first become aware of the recording side of music?

Well, my dad, when I was very little, he would go in the studio; I loved being there. I remember very early memories of Chips Moman’s studio on the east side of Nashville; he had an arcade and a poker machine, and I remember going there at night thinking this was the coolest place I had ever seen.

When I was 13 or 14, I got into Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral and was so blown away that this one dude had done all of that.

I played drums first, and then piano. Guitar was last, kind of out of necessity. I’m still not a great guitar player. But I realized, hey, I can play keyboards and I can run a computer and do all that. So I got this software, Studio Vision Pro, and it was what Trent Reznor used.

I would save up money as I got a little older. I would go to Sam’s Music in Nashville and buy little drum machine brains, and I had a cool Korg keyboard that one of my dad’s keyboard players wasn’t using anymore. So I started piecing a home studio together and put together a band. I would program all the instruments and I had two guys who played guitar.

My parents had put together a college fund, but I was like, “I would rather not go to college and [instead] get a starter Pro Tools kit.” I spent two years messing with that and recording a lot. And then I was like, I’m moving to L.A., I’m going to be in a band and I’m gonna bring all this shit with me.

It wasn’t until I met Dave Cobb that I started recording again; he flipped me back into that world and became somebody who taught me a lot about gear.

When did you start making records for other people?

That was really a natural progression that started when Dave Cobb moved to Nashville, around 2010 or 2011. I produced Marilyn records, I produced a record with Jason Baldwin and a band called Fifth on the Floor. I did records with a couple of other bands along the way and started getting my own legs.

Once I got to a place where people wanted me to do their records, I realized that, as an artist, I only got to do a record a year, maybe two in three years. To do a record every month for a different artist, to jump into someone else’s band and their concept, apply it through my lens and then jump to another one, it became very apparent that this is what I enjoy the most. I love my own stuff, but playing on the road and doing shows, that’s just time that I can’t be in the studio and be making up new stuff.

It’s interesting when those lines blur. When you’re playing on records that you produce, do you feel like you’re moving in and out of a producer role?

When they happen, they’re as important as anything I’ve ever done as an artist. When you work with people, you bring the A riffs and the A ideas all of the time, and it doesn’t live in the same house in the same way, the artist side and the producer side.

But I’m using the same brain. It’s fulfilling to do a record like American Aquarium’s where I didn’t play anything on it and was just behind the console, or one with Brandi Carlile when I’m playing piano the whole time, or with Marilyn Manson where I’m writing all of the music. They all become my favorite project in the moment. And they all become like The NeverEnding Story: In that movie, this kid goes into the bookstore and the dude’s got a book and says, “This book is not safe, you can’t be this book.” I feel like that guy, like that’s my role.

I’m so glad you brought up The NeverEnding Story. I heard that you and Brandi Carlile bonded over that movie.

I love that movie! We still connect over that. I asked her to sing that theme song on the Giorgio Moroder tribute album. Right after that, she asked me to do By The Way, I Forgive You with Dave Cobb. Then about a year later Manson came, then Duff came, and Tanya came and Jamie and Hellbound Glory, and White Buffalo, they all just rolled in at once.

By The Way, I Forgive You was such a watershed moment. Did things change after that?

Yes, but not immediately. It wasn’t until about halfway through the year that people started paying attention to it. But when the Grammy thing happened, it was feeling like being in training for something for your whole life, then something happens and it’s like, “Are you ready?” I’m like, “Yes, I’ll try to be ready.” And Chariots of Fire is blazing in the background.

While I’m Living is Tanya Tucker’s first album in 17 years. How did you know the time was right, and how did you help her overcome her reluctance to record?

Well, a lot of things happened in the process. The Brandi record came out in the beginning of 2018, and I had produced the Pinball record for Hellbound Glory, a band that I love and is on my label. Hellbound did “Delta Dawn” on their record, and a friend had an idea that we should do a seven-inch for Record Store Day that on one side has Hellbound Glory doing “Delta Dawn” and then get Tanya Tucker to do one of their songs called “You Better Hope You Die Young” on the B-side. I knew my mom and Tanya were in touch recently, so I reached out and I got Tanya to do it, with some reluctance.

She was so cool, and I was just blown away by the power of her voice. A couple of days later, she was leaving, and I said, “I would love to produce a whole record for you.”

What was her reaction?

She said yes; I don’t think she thought much of it. A couple of days later, I flew to New York to play with Brandi on Colbert. When I got there, two things happened: In the hallway going up to soundcheck, Greg Nagel, who runs LCS, Brandi’s label, says, “Duff McKagan’s got a new record, would you be interested in producing it?”

Then I went to the stage and Brandi was there, and I said, “Hey, I just recorded Tanya Tucker; she sounds awesome,” and she was like, “OMG! I love her!” I told her, “You should do it with me!” Immediately, Brandi and I started cooking up this thing without Tanya being involved yet, even though she knew I wanted it to happen.

So I wrote her and told her about Brandi; she didn’t even know who Brandi was. Brandi and I were over here, cooking up this vision for the record; Tanya and The Twins, her writing collective, were writing songs. I was picking songs and finding old songs, and we kept trying to present it to Tanya and we couldn’t even get it to her. We had to get a CD physically to her, and then she said, “I don’t like them, I don’t think they’re good.”

We were supposed to record on January 7, 2019, and on Christmas Eve Tanya called and told me she didn’t think it was going to happen. She was halfway to L.A., but luckily her bus driver was sick or had a gig, and my bus driver happened to be driving for her. So I write to my bus driver and tell him, “If she turns the bus around, you tell me right away so I can at least call her and stop this from happening.”

It kind of sounds like you kidnapped her.

A little! The night before, she came to my house and had a drink, and I said, “Please, just trust me. If you hate it, you can just throw it away.” The next day she met Brandi, and even in the studio she didn’t know what was going to come out of it. I think she didn’t have both feet in it all the way. That’s when we thought, “Let’s go ahead and mix it, and we’re going to play it for her in front of a small group of people so she could see their reaction.”

We immediately mixed the record with Trina Shoemaker, who is an amazing mixer. [Ed. note: Shoemaker won her fourth Grammy for her work on the Tanya Tucker album.] We played that for Tanya in front of label people. When we did that, that was when she got it. That was Brandi’s idea, and it was brilliant because it showed her how other people would react when they heard it, and it got her to finally understand that she had done something really good.

Also, this was the first record she had done since her father had died; he was always at the helm of her career. So when we did this, we were validating her and honing this record in with a lot of care.

It seems like you connect with artists who want to express themselves in a vulnerable or confessional way, or who want to make an album with a social conscience. What do you think is behind that?

I don’t know, maybe it’s that the type of friendships that I’ve made have been with people that have something to say. I care about social issues, but I think it tends to be that I live in my childhood a little bit, and there’s some honesty about that. I’m attracted to people who share that. All of them are people who felt that the sky is the limit, and I’m that way, too.

Do you feel like fans are more open today to nontraditional sounds in country or rock? Is it easier to get them to follow along when you make, say, a Giorgio Moroder tribute record?

Yes, there were times, like the Moroder record and also my Black Ribbons record, that when I did it, they were not ready. I’m not saying this to toot my own horn, but Black Ribbons was definitely Dave Cobb’s and my creation. Then you look 10 years down the line and Sturgill did the Sound and Fury thing; that definitely helped people get in the mindset for things like that.

I feel we were alone doing it. Just like Hank III was alone crossing metal and country and the satanic thing. Nobody was ready for that. But when he did, it led to bands and artists really expanding the concept of country.

Look at when David Bowie did Ziggy Stardust, or even weirder, like he popped in China Girl the way he did, or like on [Iggy Pop’s] The Idiot, which Bowie produced. That stuff was out there at the time, and now people knock that stuff all the time, and say, “That was inspirational.” People like Pink Floyd, they redefined the boundaries of what music was. They were inspired by Syd Barrett, who was their predecessor. Guys like my dad, people said, “That’s really traditional country,” but when he came out, that was way rock for country.

Did he talk about his rock inspirations?

My dad was obsessed with Buddy Holly, who had guided and mentored him. He was so into the sound of the drums, and blending that in country music. Richie Albright, who was his drummer, kind of invented that style of drumming for country. The two of them invented the sound that became the sound of country in the ’70s, and now people knock that sound like that’s old, traditional outlaw country. That was not traditional, that was way out of the box and created a new view for people.

I want to end with a quote from Brandi Carlile. She said, “I knew I wanted to work with Shooter the first time we discussed our hopes that our generation and peers would turn their heels on the dangers of disappearing down a path of retro-mania. Shooter knows that right now matters, that this moment is profound enough. What would Woody Guthrie say now? He’d probably look and sound a lot like Shooter Jennings.”

That’s a very kind quote. I know what she means: She read an article where I was just spouting off, where I was saying that you run into these country artists who are dressing like it’s 1967, they’re dressing like gunslingers with long beards, and I’m like, “You were playing Pokémon six years ago!” That was my whole point: Being true to who you are is very hard to do, especially when you’re trying to create something. But, if you can do it, well, it’s the most unique thing you can do.

It’s a long game, it’s not a short game. That long game, it’s going to come out that people are changed by you because you said, “It’s okay to be me.” Because at the end of the day, we don’t have to be anybody but ourselves around each other. When we make music, it’s the same way, you know what I mean?