Photo: Norman Seeff

It somehow seems fitting that Ray Charles’ swan song, a duets album on Concord Records called Genius Loves Company, finds the legendary singer creatively joining with several generations of vocalists who admired, respected and were influenced by him. At the end of his long road — a 53-year career — Charles was weak and sick, but at least he wasn’t alone. He was working almost until his final days surrounded by musicians and singers (as well as family and friends), a trooper through and through, giving everything he had, even when there wasn’t much to give. His duet partners didn’t care that they weren’t working with a man in his prime; they were just happy to be sharing a song with this musical titan.

And what a collection of singers it is: Elton John, Willie Nelson, Diana Krall, James Taylor, Bonnie Raitt, B.B. King, Norah Jones, Michael McDonald, Van Morrison, Natalie Cole, Gladys Knight and Johnny Mathis. There aren’t many artists who could pull off so many stylistic shifts on one album — from lush pop ballads to blues to soul to gospel to jazz — but Charles was, in a sense, the original crossover artist: Boundaries meant nothing to him. He played every style and turned it into Ray Charles Music. And that’s the case on Genius Loves Company. Occasionally faltering and diminished, Charles still digs deep to find the emotional truth at the center of these songs.

Concord Records A&R chief and producer John Burk

The album was the brainchild of Concord Records A&R chief (and producer) John Burk, who notes, “Two of Ray’s most outstanding feats in music were that he was highly influential to so many vocalists and that he was also able to cross over genres, which made him the ideal focus of a duets project. One of our main goals was to try to put him in the room live with the guest artists — the way he used to make records. He makes magic in the studio. And as I learned from working with him, perhaps his greatest gift is his ability to really communicate what a song is about and the emotion behind it. And when he works with another artist, he draws that out of them, as well.”

From the earliest days of his career, Charles was an artist who liked to assert control over his albums. He was a magnificent arranger and bandleader, a shrewd businessman and he even learned engineering from Tom Dowd and others at Atlantic Records in the late ’50s. (See “Classic Tracks,” page 130.) For the past 40 years, Charles mostly recorded at his RPM Studios in Los Angeles (it was declared a city landmark in April 2004) and the bulk of Genius Loves Company was cut there, using some of Charles’ regular musicians and his longtime engineer, Terry Howard. Burk produced most of the album, but five tracks were helmed by Phil Ramone, who used Ed Thacker as his engineer. The three songs that were cut live with a full orchestra on the Warner Bros. L.A. scoring stage were co-produced by Howard and engineered by Bobby Fernandez. SACD pioneer Herb Waltl also earned a co-production credit for his assistance on the project, and it was he and Howard who facilitated Burk’s initial meeting with Charles. The album was mixed by Al Schmitt at Capitol’s Studio C on a Neve VR.

Burk notes that having Ramone onboard for the project was particularly important. “Phil is clearly one of the greatest producers and engineers ever. He’s also a friend and I consider him a mentor,” he says. “When I first talked to Ray about doing the project in his own studio, which has such a distinctive vibe and so much history, I wanted to bring Phil in right away because there’s nobody better at making a room work. We ordered some baffling and did various other things to make the room sound better — Phil even brought in a huge garden umbrella to put over the drums because they were leaking all over the room. He put that in and taped in some foam and that really helped.”

“It’s a very bright room,” Ramone comments, “but I still didn’t want to use a lot of isolation. It’s decent-sized, maybe 40-by-30. It has a sort of late-’50s, early-’60s feeling, which is, of course, when he made some of his greatest music. Ray is very fussy about what he wants to hear, but he’s also very cooperative and was open to suggestions.”

It was Ramone who chose the vocal mic that Charles and his partners used. “We tried a couple of things at the outset,” he says. “We started with some Neumanns, but for some reason, they didn’t feel right to me so we ended up using Audio-Technica 4060s. Once we settled on that, we stuck with it. I like to get things early; I’m a first-taker. I don’t want to be changing mics on take five — if we get there — especially on someone like Ray Charles.” Ramone’s vocal chain on Charles also included a Summit EQ and a Neve 1073 preamp. “I like to go with the simplistic best,” Ramone comments. “I like API and Avalon [preamps], too. I’m good with any of the top-of-the-line Class-A amps.” The project was recorded to Pro Tools, and Ramone notes that he used RPM’s Quad 8 Virtuoso console mostly just for monitoring.

Once Charles, the producers and the duet partners agreed on song choices, the work turned to picking appropriate arrangements. “It was so many different styles, you wanted to treat them differently,” Burk says. “There was a core band, which was pretty much Ray’s guys — bass player Tom Fowler is probably the main one there — and then for drums, Ray wanted Ray Brinker, who has worked with [jazz singer] Tierney Sutton and others, and Randy Waldman did a lot of the piano work. Billy Preston was on the B3, and then there was a whole variety of guitar players.”

As for the vocal arrangements, Ramone says, “Where I could prepare [the duet partners], I’d send them an idea of the arrangement, which would usually give a sense of where they might come in. But you learn your lesson fast with Ray, because he’s such a great arranger himself and he’s full of ideas and he always seems to have an opinion about how things should go. So you might come into a session thinking it’s going to go one way, but with Ray, there’s always the possibility that he’s going to change it once you’re in the room with him. If you’re a singer and he feels you’re stretching or straining and he doesn’t like it, he’ll change it. Or if he wants you to strain a little, you’ll do it. He’s so intuitive about how it should go.”

“He has a very clear vision of what he wants,” Burk adds, “so a big part of the [producer’s] job is to get that for him. A lot of the work is the dialog you have with him before the date. Then when you get into it, there’s a lot of give and take, but now and then, it’s going to go a certain way and that’s all there is to it.

“You don’t tell Ray Charles how to sing,” he continues. “There were certain times where he’d say, ‘That’s it. That’s the take.’ Sometimes I’d ask him to try something and he’d say, ‘Okay.’ Other times, he’d say, ‘No.’ He knew when he got what he wanted, and he didn’t do a lot of takes. Every now and then, he’d come back later and swap in a word or a line, but in general, that didn’t work as well as the vocals he did in the moment with the other artists.”

As is frequently the case with these sorts of all-star projects, scheduling turned out to be one of the biggest challenges; at the beginning, Charles’ demanding agenda proved to be daunting. “He was still touring in June [2003], and he’d say, ‘I have three days — the eighth, the 14th and the 29th’ — so we’d scramble to see which artists we could come up with who were free,” Burk says. “When he stopped touring, he came into the office every day and the album became his main focus, so that actually made our job a little easier.”

The first studio session, with B.B. King, came together in July 2003. “I could tell his hip was bothering him,” Burk says, “but he was an incredibly strong guy. He’s someone who overcame obstacles throughout his life. He never let his disability get in his way. He was a recording engineer, he played chess, he drove cars — he did everything. His attitude was, ‘I’m fine. I’ve got a little somethin’ I’m dealing with. Don’t worry about it. Let’s go to work.’ So he might have an off-day. But he was a man of his word and a man of commitment. There was a day when he came to a session and he really wasn’t feeling well, and I told him, ‘Ray, please don’t ever do that again. I’m more than happy to reschedule.’ But his feeling was, ‘I said I was going to be there,’ so he showed up. He always showed up on time, ready to work.”

For engineer Howard, who had worked with Charles for nearly two decades, he could tell that his boss was not well, “and I know B.B. was kind of shocked by how weak Ray seemed. But that session was one of my most memorable, because when you hear Ray singing, you really hear the pain in his voice, but when you hear B.B. coming in, you hear the strong shoulder of a friend that someone like Ray could lean against. Ray was already frail: When he talked, he sounded like an old person. But the fire in his soul was still there and once the song started, that frail voice left him and Ray Charles the star entered the building. He belted it out and we did it in just a couple or three takes.”

Ray Charles with Bonnie Raitt

Another of Howard’s favorites was the session with Bonnie Raitt, who Charles admired “for taking the time to really work on the song with Ray, changing a part a little here, changing the bridge this way. It was amazing to see two of the most talented people in the world crafting a song before your eyes. I know Ray really loved that track.”

Willie Nelson

Originally, Burk says, he had not planned on including orchestral tracks on the album, “but Ray had an idea about a song that he wanted to do with Willie Nelson [“It Was a Very Good Year”] with a full orchestra. And this is something Ray would do from time to time. He said, ‘I’ve already got the arrangement written and I’ve got to tell you, it’s going to be awesome.’ He was so convicted, I said, ‘Okay, let’s do it!’ before I heard the arrangement. The arranger, Victor Vanacore, does these amazing detailed demos of his charts, and when I heard it, I was knocked out, too.” One thing led to another, and soon Michael McDonald and Johnny Mathis were also cutting live with the orchestra at the Eastwood Scoring Stage, which is equipped with an SSL 9000J console.

Arranger Victor Vanacore

By the late winter of 2004, Charles’ health had declined precipitously and finding moments when he could work on the project became difficult. The knock-out duet with Elton John on John’s “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word,” cut last April, turned out to be the project’s final recording.

“I must admit, I was a little shocked at how frail he seemed when we got together in March,” Ramone says. “Compared to the way he was the previous fall, he seemed very, very fragile. He whispered to me at one point, ‘I’m really not well.’ I wanted to cry right there. People who were around were weeping in the control room, it was so emotional. But, of course, you always hope and believe that someone will get better, and I think we all believed that he would get better. I’ll say this about him: He funneled every bit of energy he had into that performance. The chemistry between Ray and Elton was just incredible.”

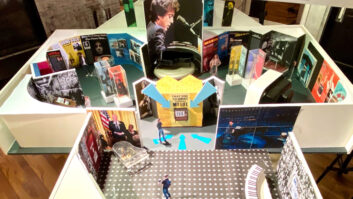

Orchestral session for Genius Loves Company at Warner Bros.’ Eastwood Scoring Stage, with arranger Victor Vanacore conducting

Though historically Charles was deeply involved in the mixing of his albums, his failing health kept him away from Schmitt’s mixing sessions for the most part, and, as Burk notes, “At a certain point, he was not leaving his place much, so we set up an edNET system that would tap him into the studio so we could play the mixes for him. Even then there were times when he couldn’t really give it his all. Once I got a CD ref to him, though, he played it nonstop in his car and I know he was happy with how it came out.”

Charles succumbed to liver cancer on June 11, shortly after the album was mastered. “At the time, he wasn’t really admitting to any of us how ill he was,” Burk says. “But you look back at some of the songs he chose and you start to wonder: ‘Was he trying to say something?’ ‘Was he trying to make some final statements?’ I think maybe he was.”