“He’s doing what?!” That was the reaction from the owner of one major Manhattan studio to the news that Simon Andrews, principal owner of Right Track Recording, had embarked on an ambitious venture to build a massive new music studio complex on the city’s extreme West Side.

Surprise, amazement and the suggestion of a lapse of sanity are all understandable reactions, given the circumstances. New York music facilities have, on average, been reporting at least decent returns in the past two years. But in that time, the music studio business has become much more challenging. New technology and Internet distribution schemes have brought radical changes to the music and entertainment industries, and the relentless proliferation of project studios has only added to the pressures on larger facilities.

But seen through the eyes of Simon Andrews, these forces only underline the timeliness of his new vision. “This is the perfect plan at the perfect time,” says Andrews as we tour the 100-year-old warehouse building that will house Right Track’s newest facility — a 10,000-square-foot orchestral recording studio. The idea for the studio germinated nearly six years ago, in 1995, when Andrews noticed that the demand for large-scale tracking and orchestral sessions was on the rise. “We’d always done orchestra dates and Broadway show recordings,” he explains. “But there really hadn’t been a studio in Manhattan that could accommodate truly large orchestral sessions since the great label-owned orchestral rooms, like Columbia’s old church or Decca Studios or RCA Studios, the last of them had been closed over a decade ago.” With plans in place for a huge new production facility at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and expansions slated for the Kaufman-Astoria and Silvercup Studios production facilities in Queens, it seemed inevitable that film and television work in New York would increase. “It seemed logical that New York needed a studio that could do for orchestral music what those grand old rooms did,” says Andrews.

IT’S ALL ABOUT LOCALE

Starting in 1996, Andrews spent three years scouring Manhattan for the right location, a task complicated by a soaring real estate market. Property values rocketed during what turned out to be the longest economic boom in U.S. history, and luxury residential construction and rehab effectively removed millions of square feet from the commercial pool. Eventually, in February 1999, Andrews found a 35,000-square-foot building on the last block on West 38th Street, in sight of the Hudson River. The low-rise neighborhood’s anonymity helped shield it from gentrification during the ’90s, though the brick warehouses and turn-of-the-century stables were rapidly becoming home to outposts of the New Economy — the Starrett-Leigh Building, a former warehouse, is now home to Martha Stewart’s Living and print/online media phenom Inside.com.

The building that Andrews found also had an important and increasingly rare asset — an “enlightened” landlord who offered (after five months of negotiations) a multidecade lease with future options that Andrews had been seeking. Andrews’ Right Track team — technical director Dominick Costanzo, producer/engineer Frank Filipetti, and general manager and director of operations Barry Bongiovi — swung into action and developed a collaborative facility and acoustical design, which was realized by studio design architect Denis Janson, of the New York-based Janson Design Group. Janson devised a new system of steel trusses to replace the numerous interior posts that supported each floor, and demolition began in August 2000, with actual construction starting in October. (The original Right Track, founded in 1976, and in its present West 48th Street location since 1980, will continue to operate its existing three studios indefinitely.)

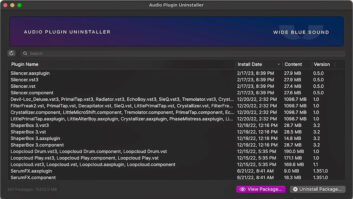

At the time of writing, work crews were still welding steel and pouring concrete. Girders sprang skyward from the building’s third and uppermost floor, destined to support a new ceiling that rises 37 feet above the studio. According to the designs, the control room will retain the original 16-foot ceiling height but, at 1,000 square feet, will be as large as some recording studios. It will be equipped with a 96-input SSL 9000 J analog console fitted with a modified and removable center section, specifically designed for Right Track by SSL to allow the board to be seamlessly reconfigured for film scoring/mixing as needed. A large plasma video screen above the center section will serve in place of the CRT in the console itself. Monitors will include fully soffited Genelec 1035B speakers and 1094 subs in a 5.1 multichannel array designed to be upgraded to a 7.1 configuration.

The main orchestral room will be massive (4,400 square feet), with two dedicated iso booths (380 square feet and 300 square feet, respectively), the larger of which may be bisected by folding glass doors. An additional 200-square-foot airlock will serve as an iso booth, and there will be a dedicated 120-square-foot vocal booth just in front and to the side of the control room. Machine room, lounges and producers’ offices will occupy a further 10,000 square feet.

The acoustical design of the orchestral room was refined in part by Bongiovi, who visited large scoring stages and orchestral studios in Hollywood and London to find out what makes them work. “There was one time when Frank [Filipetti] and I walked from one end of the room to the other and noticed the change in the sound,” recalls Bongiovi, a New York studio veteran who previously worked at Power Station, The Hit Factory and Sony Classical before coming to Right Track in 1995. “We pulled up an access cover and were able to see that different types of construction were actually used in different parts of the studio itself.” For the new Right Track facility, a system of separate floated concrete slabs will provide such a high degree of isolation that “a basketball game could be played in the room while a vocal was being done in the booth,” says Costanzo.

LOGISTICALLY SPEAKING…

Andrews estimates that accommodating New York City’s myriad and often mystifying building codes added nearly three quarters of a million dollars to the approximately $5 million overall cost of the project. Easements, facade setbacks and other structural elements actually varied within the building itself, depending on what had been grandfathered in during previous incarnations of the structure. The first floor facade can extend to the lot line, for instance, but the upper levels had to be set back. New codes required that all new support steel be coated in fireproofed material. New stairways and firewalls had to be built to comply with fire codes. The new structural addition on the top floor, which gives the orchestral room its defining height, had to be cantilevered, rather than supported directly from below. Despite these requirements, the Right Track team felt it was important to make the most of the decorative and aesthetic characteristics of the building. The arches over the front doors and windows have been retained, as well as the exposed brick walls that give character to interior common areas such as offices and lounges.

“For some of the [structural matters], we might have been able to get variances,” says Bongiovi. “But that would have taken six to nine months, if it happened at all. We had to stay on a schedule because every day the studio isn’t up and running, it’s not returning on its investment.”

Which brings up the subject of rates, an almost existential subject in the studio business. On the one hand, Andrews promises that the new facility’s rates will be “comparable and competitive,” but he acknowledges that the film and music industries have widely differing rate structures, and that rates for similar facilities can be as much as $8,000 per day. “We’ve dedicated 10,000 square feet of space for one studio, enough to hold four music studios,” he points out. “The rate should be commensurate with that.”

WORKING WITHIN THE WALLS

[THE ORCHESTRAL STUDIO] IS JUST THE BEGINNING OF A LARGER AND WHAT WE BELIEVE WILL BE A VERY PROFITABLE VENTURE THAT REFLECTS THE WAY THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY WILL BE, NOT THE WAY IT HAS BEEN.

— Barry Bongiovi

But rates are just part of the overall economic projections for what is planned to be an even larger facility in the future. The building’s second design phase, which has not yet been scheduled, calls for a large part of the second floor to be removed to create a two-story-high second studio, estimated at 40×45×25 feet, with an 800-square-foot control room. Intended mainly for music tracking, the “phase two” studio will have its own large control room, up against the south side of the building. Looking even further down the road, Bongiovi says that the remaining square footage — which will still be substantial even after two studios and their offices and lounges are built — is part of a still-evolving plan for various multimedia purposes. While this part of the vision is not yet completely defined, Bongiovi stresses that flexibility and the ability to adapt quickly to changing market and technology requirements will be paramount.

“What we realized in the last few years is that studios had to become much more flexible to deal with the way the music business was changing,” he explains. “Scheduling has to be able to turn on a dime, and you have to be able to deal with multiple formats. Also, with [personal] studios on the rise, for a [conventional] facility to be successful, you have to be able to interface with them easily, and at the same time offer services and capabilities that no personal studio could ever dream of.

“[The orchestral studio] is just the beginning of a larger and what we believe will be a very profitable venture that reflects the way the entertainment industry will be, not the way it has been,” Bongiovi continues. “Studios used to deal with a record label called Warners; now, we’re dealing with a multimedia and Internet company named AOL Time Warner. Sony Music is talking about putting its entire catalog online. [Audio] mastering is becoming authoring. The challenge is to build a large facility that is also able to adapt itself quickly to change, and still keep the same level of service that made Right Track as successful as it has been. I think we’ve got that here.”

“The real economic bottom line is that the need for large, well-designed acoustical spaces will never disappear, because they fulfill a unique need that cannot be duplicated electronically,” concludes Andrews. “As the studio business itself has had to deal with all sorts of issues in the past 10 years or so, remaking itself to deal with the harsh realities of home studios and the like, the grand orchestral rooms have been able to float above all of that. And that’s where this facility picks up that legacy and brings it back to New York.”

Dan Daley is Mix‘s East Coast editor.