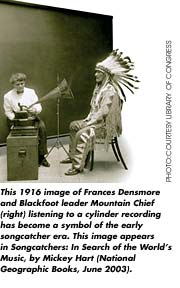

Mickey Hart, longtime percussionist for the Grateful Dead, knows athing or two about world music and field recording. He’s lugged tapinggear to Egypt, outfitted a recording expedition to New Guinea, capturedthe Tibetan Gyuto Monks in all of their glory and searched outindigenous music all over the world. As a very active member ofthe National Recorded Sound Preservation Board at the Library ofCongress, he has supervised the digital transfer of many historicrecordings: everything from Leadbelly to Hawaiian kahuna chants.He has produced (and played on) numerous world music albums, and he haswritten three acclaimed books on the subject: the largelyautobiographical Drumming at the Edge of Magic, Planet Drum andSpirit Into Sound: The Magic of Music. But his latest,Songcatchers: In Search of the World’s Music, is the first todeal mainly with recording. Published by the National GeographicSociety and co-authored by National Geographic staff writer KarenKostyal, Songcatchers depicts the fascinating story of fieldrecording by focusing on the brave and driven men and women who enduredtremendous physical hardships — and technical limitations —to record “ethnic” music around the world, from the late19th century to the present day. Copiously illustrated with photos, thebook also traces the development of recording technology, from thefirst Edison cylinders through the introduction of the ever-dependableNagra and beyond.

Hart speaks excitedly about the pioneers in the field: “Iwanted to tell their story, because the work they did is so important.None of them had to do what they did. There was no money in it;far from it. But they did because they believed there should be apermanent record of these cultures, which were all starting to changeand even disappear at the end of the 19th century and the beginning ofthe 20th century. I really believe that these are some of our greatestcreations: the art of a culture. Thousands of years of evolution wentinto that. We base what we do on the things that have been done beforeus, and that includes music, of course. I mean, if there hadn’t beenany jug bands or blues, there might not have been a Grateful Dead or aPaul Simon or a Santana. That’s why it’s really important to hear thesekinds of music and recognize them as great works of art. Recorded musichas been a really important part of making us understand thedifferences and sameness of us as a people, as a species.”

Who are some of the field recording figures Hart particularlyadmires? “All of them,” he says with a laugh. “Everyone of them! The story starts in 1877 with Edison’s seat-of-the-pantsinvention; brilliant, but very primitive. Thirteen years later, JesseFewkes gets a hold of it and starts this revolution: On March 15, 1890,in Calais, Maine, he became the first guy to walk out on the field androll wax. He was an ethnologist and he recorded all of these songs andtales of the Passamaquoddy Indians. He later recorded the Zuni andother tribes. So he’s a major factor. Then there were people likeHenrietta Yuchenco, who took a Presto disc cutter to the mountainousregions of Mexico. She has an amazing story: bandits, romance,intrigue. Then there’s Laura Boulton, who you see with Geronimo, withthe aborigines in Australia, with the shamen in Siberia. And, ofcourse, better known is the John and Alan Lomax story: Leadbelly andthe great folk and blues musicians of the South.

“I view myself as an extension of those songcatchers, butobviously I haven’t had to go through what they did: being out therefor weeks and months at a time with primitive equipment. I didn’trecord 40,000 cylinders the way Bartok did in Romania, traveling aroundby donkey carts and canoes. I live in a different era, but I’ve had myadventures in the field, too.”

Hart says that he also wrote the book to encourage the preservationof recordings yet to be discovered. “The major recordings arestill in the attics of the world,” he says. “The childrenand the grandchildren of the recordists are just coming to grips withtheir mortality. That’s what happened with the Fahnstock recordings[recordings made in the South Seas in the early ’40s, but“lost” until the ’90s]. If the grandson didn’t fall on thatbox of discs, it would have never gotten to the Library of Congress.There are lots of stories like that. Right now, we’re getting it by thebushel, and some of it is great and some of it is not so great, justlike everything else. Just like Grateful Dead music, where someconcerts are just not good and some border on the miraculous. Some ofit is poorly recorded, sloppily played and has limited value. But wehave to preserve and save what we can, while the saving’s good.

“Plenty of it has been lost already,” he continues,“and lot of it is endangered; it’s in crisis. There are discsthat have crumbled and tapes that have sticky shed and are basicallyunplayable. It’s heartbreaking when you go into a collection and someof it doesn’t play at all, or just a piece of it plays. It’s reallysad. Sometimes, it gives its life on the transfer. When I transfer it,I’ll take it right to 1630, the digital domain, and that may be thelast time it will ever play. But if we’re lucky, we get it, ormost of it.

“So what we’re doing at the Library is identifying thecollections in crisis and digitizing as fast as we can. You could callit triage. It’s a race we’ll never win, but we have to keeptrying.”