When Mix asked me to write an article on acoustic fixes for small home studios, I said, “No problem, I’ve analyzed plenty of small rooms.” Then they asked me to write it from the perspective of someone who couldn’t afford an analyzer, and I said, “Oh shit.” Although there are very few rules of thumb, I’m going to try to give you some guidance in solving some of your acoustic problems on your own. This process requires some intensive listening at times, but, hey, there’s no time like the present to hone those skills: Make your ears your analyzer. Because this article is aimed at the “do it yourselfer,” the acoustic solutions are the cheapest I could think of and some assembly is required.

SPEAKER SETUPIt is very important that you become completely familiar with the speakers you are going to use. Take a good look at the manufacturer’s frequency response charts, but remember that these are anechoic measurements. As soon as you put your speakers in a room with boundaries (walls), the bass response will start to change significantly. Bass response will build up even more when you place a speaker against the wall (half-space loading) or in a corner (quarter-space loading). But the response charts are useful for knowing what the limitations are. For example, an NS-10 will roll off dramatically below 125 Hz, so you don’t have to be too concerned about deep bass problems when positioning this speaker. You also want to pay close attention to the recommended position for proper phase alignment. You want to make sure that this alignment point intersects your ear level. For some speakers it’s directly aligned with the tweeter. For others it’s a point between the woofer and tweeter. It depends on the design, so check the manufacturer’s literature.

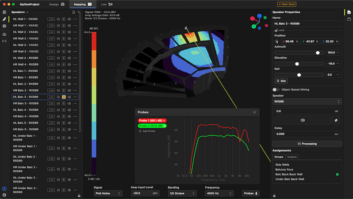

Before even thinking about acoustic treatments, we need to optimize the speaker positions in your room. Step one is to determine which wall your speakers should be on. If your room is square, it doesn’t matter. If your room is rectangular, it all depends on the dimensions. To figure out which wall to use, place one speaker on each wall and at listening height in approximate position. Run a mono send from your CD player to one speaker at a time and do some serious listening to the bass. You should be able to get a feel for which speaker has a flatter bass response. More bass is not necessarily better. Listen for smooth and connected bass from mid down to low. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of just how different the walls can be and what you should listen for. This room measures 15×9 feet.

For Dustin Hoffman, the word was “plastics.” Well, I have just one word for you: symmetry. If you do just one thing right, it should be to set your room up as symmetrically as possible. What does this mean? Your speakers must be placed symmetrically in the room or they will have different frequency responses. This means that your music will sound different in the left and right speakers, your center image will be off-center and your product will not properly collapse to mono. Don’t believe that old wives’ tale that near-fields are not affected by room acoustics. That goes against the laws of physics. So your mission, should you choose to accept it, is as follows: Get a tape measure and make sure that the left and right speakers are equidistant from the side walls and from the front wall.

Why is the above true? Below 200 Hz your speakers are fairly omnidirectional. The signals that bounce off the front and side walls are going to mix in with the direct speaker signal. This delayed bounce will cause comb filtering. The time delay, and thus frequency, of interaction is dependent on the speaker distance from the walls. If the left and right speakers are different distances from the walls, the cancellations will occur at different frequencies. This is also true for first-order reflections above 400 Hz, which I will address later. Figures 3 and 4 give you a demonstration of what happens to the bass when speakers are placed asymmetrically in a room.

Now we need to determine how far out from the front wall the speakers should go. This will require more listening tests. Listen to both speakers in stereo. You should move the speakers six inches at a time forward or back. In a small room, these increments can make a big difference. Once again, you are trying to find the smoothest response. I realize that there may not be much space, but do the best you can. Believe it or not, sometimes the best place for a speaker is even up against the front wall.

At this point I want to mention the evils of console reflections. Figures 5 and 6 show why your speakers are better off several inches in back of the meter bridge. Now, I realize that you can’t do this if you have one of these all-in-one workstation pieces of furniture, but you should be aware of these tight reflections bouncing into your face. If you have the freedom, move the speakers back. I have a 2×2-foot plastic mirror that I like to lay on top of the console surface. If I sit at the console and can see the tweeters in the mirror, I know I’m in trouble. Time to move those speakers back so there’s no reflection in the mirror.

Your speakers and mic should also be set up in an equilateral triangle in order to get good stereo imaging. Measure the width of your room and place a microphone stand in the center, two to three feet back from the console arm rest. You want a nice wide sweet spot, so the width of your console or workspace will determine how far back you place the stand. The measured distance from tweeter to tweeter should equal the distance from each tweeter to the mic stand-the distance will depend on your room size and the width of your console (see Fig.7). Remember also that the typical small monitor is designed to be used at a distance of no more than six feet. Adjust the distance between your speakers remembering that each speaker needs to be the same distance from the side walls. Now aim the speakers at the mic stand, keeping in mind the proper phase alignment.

Doors are an important factor in your workroom. The bass can vary radically depending on whether the door is open or closed. More often than not, doors are in corners, and have a greater effect on one speaker than another. You want to avoid that, so I recommend keeping doors closed. You can do some listening to figure this out.

ACOUSTIC ISSUESNow that we have the speakers in place, we need to address the first-order reflections. These are the reflections that arrive at the mix position within the first 19 ms of the direct signal. (That’s about a 21.5-foot path length difference.) Your brain cannot tell the difference between a direct and a reflected signal in this short space; you think it is all coming from the speaker, which is the closest path. The result is that the reflection is convolved into the direct signal, just like a delay line. Of course, this causes comb filtering and thus cancellations in the frequency response. That results in imaging problems as well as phase problems. Bad boogie.

Identifying these reflections is quite easy. Above 400 Hz, sound acts a lot like light, so simple geometry (ray tracing) can be applied. Use that plastic mirror I talked about above. Have a buddy sit at the mix position and place the mirror flat against the left wall. Move the mirror around until your buddy sees first the left and then the right speaker reflected in the mirror. Have your buddy cover the entire mix area when looking in the mirror. Mark each area so you can treat them. Do the same for the right wall, the ceiling and the back wall. If you set your room up properly, the treatments for the left and right walls should be fairly symmetrical. Now measure the distance from the speaker to the mix position (direct path). Then measure from the speaker to each marked area and back to the mix position (reflected path). Subtract the direct path from the reflected path. If it is less than 22 feet, you should apply treatments.

There are two choices for treating these reflections: absorption and diffusion. For the side walls and ceiling, I like to use absorption, and here’s why. An absorber removes the energy, but a diffusor spreads out the energy in space and time. This means that the diffusor creates many smaller reflections of lesser energy. If I do an impulse response of a side-wall reflection, both diffusors and absorbers appear to eliminate the reflection. But if I take a reading of coherence, the absorber gives a good reading because the offending reflection has been removed. The diffusor’s coherence reading is not so good, because the reflection energy still reaches the mix position, albeit reduced and spread out in time.

For the side walls and ceiling, an inexpensive solution is 6-pound-density, 2-inch compressed Fiberglas, sometimes called spinglass. (It comes in 2×4-foot sheets and is available in many large building supply stores.) Cut the panel to fit the marks you made earlier. I often make the treatments a little larger than the area of reflection. The Fiberglas should be covered with a fabric that is acoustically transparent. Go to your fabric store and pick out something with a very open weave. You should see some light pass through, and if you hold it over your mouth, you should easily be able to blow through it. For neat looking panels, build a 1×2-inch wood frame around the panel and stretch the fabric over it. Don’t do entire walls with these types of panels, however; they will disproportionately damp the high-end reverb time. Just treat the areas that are problematic-take a surgical attitude. There is nothing worse than the chesty sound of an over-absorbed room.

For the back wall, I prefer diffusion over absorption unless the back wall is closer than five feet to your head. I find that diffusion at the back opens a small room up more, and the back-wall energy does not mess up the coherence much. The cheapest diffusor I know of is to take a piece of 11/48-inch peg board and bend it to form a curve. The greater the curve, the more diffusion you get. Hold the curve shape in place with some 1×2-inch strips. Another cheap method is to use PVC or ABS pipes of varing diameter, cut in half lengthwise. Mount these vertically so that the different diameters will give you some variance.

If your speakers are very close to the front wall, try the pipe diffusors mounted on the wall in between your speakers. This can sometimes give you more front-to-back imaging (depth) as it breaks up that solid reflection. Remember that most small monitors are meant to be used in free space.

Once the walls and ceilings are treated, put on some music that you know well. Listen while standing in the corners to hear how much the bass increases. If you get a large buildup, you’ll want to trap the corners. Make the same kind of absorptive panel as explained above, using the full 2×4-foot size. Place it vertically across the corner with the top near the ceiling. Seal the bottom off with some window screen and fill the corner cavity with loose R-19 insulation. (Don’t pack it tight.) This is a general broadband type of trap and hopefully will help your situation, although properly controlling the bass is difficult without measurements.

If, after these treatments are applied, you feel that your room is still too live, some additional treatment may be needed. Try a 1-inch layer of bonded polyester. This will take down the liveness without the heavy-handedness of Fiberglas.

These tips and methods should help you improve your listening environment. Most of all, the critical listening you do during this process will improve your engineering skills and give you a good understanding of your room’s personality. Now go and make good music!