Trumpeter Terence Blanchard constantly — and seamlessly — flits between the worlds of jazz and motion picture scoring. They are by nature different, requiring distinct approaches, applications and philosophies. In cinema, he is best known for his work scoring films by director/provocateur Spike Lee, but he has also worked with such directors as Kasi Lemmons, Michael Cristofer, Joe Sargent, Leon Ichaso and Ron Shelton. In his jazz career, Blanchard’s first big breaks came during the early 1980s via icons Lionel Hampton and Art Blakey, the latter particularly known for spotting and grooming talented young musicians. Since those initial experiences, Blanchard has moved on to work with many of jazz’s top players, including saxophonist Donald Harrison and vocalists such as Jeanie Bryson, Jane Monheit, Cassandra Wilson, Dianne Reeves and Diana Krall. Since 1991, he’s pursued a career as a solo artist and has been leading his own band. Much like his mentor Blakey, Blanchard has been working with emerging and exciting young players.

Flow, his latest jazz ensemble CD, is a synthesis that showcases his current jazz sensibilities and some of the sort of tasteful electronics he’s employed in his scoring work, plus the bonus addition of Herbie Hancock as the producer. Remarkably, the recording is the first time the revered pianist has produced someone else’s project since 1987. According to Blanchard, though, he and Hancock never had a plan or agenda for the album. Mostly, they were just interested in getting into the studio and seeing if any exhilarating and remarkable music would evolve from the sessions.

“In doing all the film work I’ve composed for, I used all these other types of textures — electronics and other stuff — and became increasingly interested in it,” Blanchard explains from his home New Orleans. “I found a way to use them all on this record with my bandmembers’ compositions. So this was an opportunity to bring those things together, such as my development as a performing artist, composer/arranger and representing where the young guys are going.” The resulting album is unmistakably 21st-century jazz — structurally and harmonically more challenging and edgier than the popular modes developed in the ’50s to the late ’60s, but also with some international flavors, particularly Brazilian.

Nonetheless, the traditional method of tracking jazz hasn’t evolved much from the days of classic recordings by Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Dave Brubeck. Digital formats have mostly replaced analog, but jazz is still essentially cut live with ensembles playing together, perhaps with some occasional overdubbing. “I still like the ‘organic’ feel of playing with live musicians,” Blanchard says, “especially with the pack of guys I have in this group. There’s a synergy or oneness that happens, which can’t be re-created by mirroring, so we try to get a live sound.”

For four days in mid-December 2004, the trumpeter worked with his sextet — Aaron Parks (keyboards), Brice Winston (saxophone), Derrick Hodge (bass), Lionel Loueke (guitar/vocals) and Kendrick Scott (drums) — and guests Howard Drossin (synth programming; he often helps Blanchard with his scoring work) and Gretchen Parlato (vocals) at Jim Henson Studios in Hollywood capturing the sound of the ensemble in the big live room, which Blanchard has used for previous sessions.

“The great thing about [the live room] is that the drum area is huge and you can get a nice live sound but still have plenty of isolation,” Blanchard notes. “We got a nice natural sound on the upright bass without having to run it through a DI.” Blanchard says that the room sound is always paramount to him — more so than the recording equipment. Still, he does have some preferences in that area: He’s a big Neve fan, generally likes the old tube sound, but has remained open to new technologies. The Henson sessions more or less fit that bill — the room has an SSL J board, but he got to use a host of Neve 1073 preamps as the group cut to Pro Tools|HD.

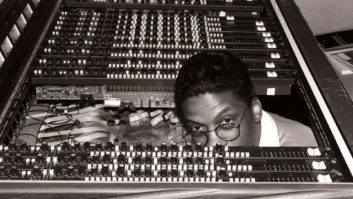

Tracking the sessions at Henson was engineer Don Murray, who has a relationship with Blanchard dating back to 1995, when the trumpeter scored Lemmons’ film Eve’s Bayou. Of the sessions for Flow, Murray remarks, “I was kind of like the bystander or the audience watching this whole dynamic go down. With Herbie there, it was so inspiring, especially for the younger musicians. He really psyched those guys up by telling them stories and talking about his great experiences with various musicians. The band was just going crazy, and I was, too.”

Blanchard and Hancock first became acquainted through their involvement with the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz in Los Angeles, where the trumpeter is artistic director and the keyboardist is the institute’s chairman. When Blanchard decided to cut a new album with his group, Hancock was the first person he approached about producing it, and Hancock quickly accepted. “Part of it was curiosity from having so many people rave about Terence’s band,” Hancock says. “I think they asked me [to produce] because I like dealing with the unknown, carving out new territories — Terence described it as ‘thinking outside the box.’ It was great to be in that environment, and all those guys could really play. On the other hand, I had been working on another project and didn’t have a lot of time to spend on Terence’s. When I heard the music the day before the recording at the rehearsal, I thought to myself, ‘This is all together and there isn’t anything for me to do!’

“But Terence really wanted me there for my presence, inspiration and spirit of exploration, which is what I’m really about,” Hancock continues. “Also, he wanted my input and suggestions as things went along. I didn’t know I would be playing on the record, but then Terence asked me to play on something and I wound up on a couple of things. In a way, I was scared because they are so good and I was a bit out of shape. I hadn’t been playing on that level for a while, but now I’m in shape again.” (Hancock had just finished touring with saxophonist Michael Brecker, trumpeter Roy Hargrove, bassist Scott Colley and drummer Terri Lyne Carrington.)

Engineer Murray described the process of cutting the tunes as “taking a little journey,” with three or four takes done as adventurous explorations. There was some editing later and minimal overdubbing, mostly add-ons from Blanchard done at his L.A. apartment studio. The title track, as suggested by Hancock, was split up and became three separate selections on the CD. Blanchard says that the arrangements of a number of the tunes were “built off the performances, not the other way around — then it really does have an organic feel. Everything starts to take shape based on the musical and emotional high points that occur on each track.” As for the electronic and other embellishments, “I heard more sustained sounds and other kinds of textures throughout the sessions,” Blanchard says. “It just seemed to be a natural progression for me, given things I was experiencing in the film world.”

Miking was quite straightforward, Murray says. “I used a combination of an RCA 77 ribbon and a [Neumann] U47 tube for Terence, recorded separately on two different channels. I’ve done this for a couple of albums and my original thinking was that the 47 was really good for the softer sounds of the trumpet but the 77 ribbon is great for focusing on very dynamic and loud passages. So I set them both up and played with the relationship later, which gives me freedom later to blend the sounds, depending on the dynamics of the song.” Murray also used a couple of Neumann M49s as room mics and on bass, a Telefunken 251 for the saxophone and an AKG C-12 on piano.

Mixing for the album, sans Hancock, was done over a four-day period in January 2005 at G Studio, a home facility owned by drummer/producer and Concord Records co-owner Greg Field. Murray had used the room to mix Blanchard’s previous album, Bounce, and was eager to go back. Murray and Blanchard mixed about three songs a day, using a TC Electronic 6000 as their primary effects.

“Terence took about a week to listen to everything, then he had me go back in for an additional day and make some changes,” Murray says. “The sounds I had in the computer were pretty good, so we just had to fine-tune them and get the right reverb and relationships. It was just a matter of balancing and retaining the energy of the performances. That was the most important thing and what’s so great about this music. The whole CD is like a suite, with Herbie there and everybody contributing so much. It all stands out to me.”