[This is the full-length version of the February, 2014 Pro Sound News cover special report]

Fifty years after the Beatles first arrived in the U.S.A., the big record release news is that the band’s entire U.S. catalog is being reissued—on vinyl. Meanwhile, recording studio technical design is moving forward into the past with renewed interest in analog equipment such as big consoles and tape machines along with a recent resurgence of larger tracking rooms.

“I would say at least 50 percent of the rooms we’re doing have large analog consoles, and vintage gear is hugely in vogue,” reports Wes Lachot of Wes Lachot Design Group in Chapel Hill, NC. “There are a lot of boutique companies, maybe more like it was back in the Fifties and Sixties. I think that appreciation for hand-wired, vintage quality equipment has gone along with an appreciation for vintage recording techniques and vintage consoles.”

He continues, “I also think there’s been an aesthetic trend towards people recording realistically again, trying to get performances out of bands instead of one person at a time.” But whereas tracking spaces have typically been 500 or 600 square feet—large enough for a four-piece band—until recently, says Lachot, “In the last year or two, we’ve seen more medium to large, 1,000-square-foot tracking rooms.”

“Six-to-eight years ago, everything was really small—tiny DAWs, tiny rooms,” says Paul Cox of Los Angeles-based Paul J. Cox Studio Systems. But the economic downturn of recent years has enabled room sizes to increase. “Property values have tanked. Commercial properties always lag a few years behind residential; you can get an industrial unit for next to nothing now,” he says.

But live rooms remain small not only in Manhattan, where space is at a premium, but also along the east coast, reports Francis Manzella of Francis Manzella Design Ltd. in Mahopac, NY. “A lot of our customers are doing urban music. They need control rooms that can fit a lot of people, along with the equipment, and they need smaller recording spaces, because mostly they’re doing overdub type recording.”

Basic physics typically dictates the size of a control room, notes Lachot. “We always try to make our control rooms a certain minimum size in order to accommodate the lowest frequencies, down to 30 Hz or so, and also ergonomically to allow room for a sofa in the rear and for a credenza.”

“It’s rare to find an artist and a producer working on a project where there aren’t 15 people involved behind them, so space is needed,” agrees Cox. And with room sizes trending larger, he adds, “Big consoles are definitely coming back.”

In fact, there has always been a market for large format consoles, says Cox, a former technician with Solid State Logic who has long been active in rehousing older desks. But manufacturers have responded to the general desire to add high-quality analog front- and back-ends to the Pro Tools workflow by developing small format consoles, some of them incorporating DAW control. “We’ve installed bucketfuls of the SSL AWS console; I don’t even know how many,” says Cox.

At the same time, he says, “The amount of outboard equipment being designed and put on the market has gone through the roof. Racks have gone from one bay to five-, six-, even eight-bay credenzas.”

“We’ve put in quite a few API 1608s,” says Lachot. “We’re also putting large API Legacy consoles into a couple of studios right now.”

“It seems like a large percentage of our customers want to get out of the box,” says Manzella. “I’m seeing a resurgence of people looking for smaller analog alternatives.”

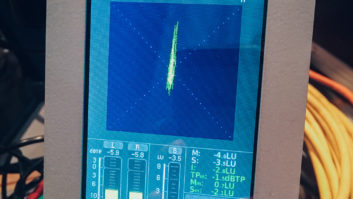

“Tape machines have been coming back for probably three years or so,” Cox also reports. “It’s been refreshing to unwrap the Studers in the basement. [Endless Analog’s] CLASP helped; I’ve put loads of those systems in.” Lachot reports a similar trend: “We’re putting analog tape machines in several rooms.”

Digital music production has effectively extended the acceptable frequency range, especially at the low end, which can be problematic if monitoring is inadequate. “Especially with stuff being done in home studios on near fields, a lot of times the mastering engineer is the first one to really hear what’s going on down there,” comments Lachot.

“Things have become louder, but having a finely-tuned system has pretty much gone by the wayside,” comments Cox. “One of the problems is people almost don’t care what’s happening above 80 Hz.”

“I sell a lot of subwoofers, I install a lot of them and I tune rooms with a lot of them,” Manzella reports. “But people don’t realize how tricky it is to integrate a subwoofer into a small or mid-size monitor system.”

Where space and budget permit, the ideal solution is soffited front wall monitors, says Cox. “Those rooms that do have a soffited wall, where everything is configured and built properly, they’re the finest sounding rooms.”

“The cost of a soffited front wall adds substantially to construction costs, but I prefer it,” says Cox. But soffited monitors can be abused, he observes: “The majority of the commercial studios, they’re only using them for listening parties.”

“We’ve always designed our large music studios to have the main monitors be a reference,” says Manzella. “Whether you buy my monitors or somebody else’s, monitors that I don’t even like, we’re going to do everything we can to make that monitor system a reference for you. That’s always just been a design philosophy around here, and we have a very high success rate with that.”

In fact, a lot of clients tell him that they don’t even use their near field monitors any more: “They’d rather listen to their main monitors softer when they’re mixing, because they do feel they’re a really good reference.”

“I think it’s true that soffit monitors really have to be done correctly, and in a lot of cases they’re not,” comments Lachot. “When professional studio designers do a room they usually know how to do them correctly. We’re crazy about some of the new near fields, like the small ATCs, but we really like the large ATC and Dynaudio soffit monitors.”

A lot of near field monitors go down to 50 Hz, he continues, and there are those that extend lower. “But to go down to 30 Hz, the boxes become so big, and there’s so much backwash that hits the front of the room and gets bounced back to the engineer out of phase, that it makes it impossible to trust the accuracy of the low frequencies. If you surface mount them into the front wall all that backwash problem goes away. We believe in RFZ [reflection-free zone] design, and soffit-mounting is a part of that.”

He adds, “We really try to insist, even for smaller home studios, that there are some good deals to be had for soffit monitors. We at least explain the physics and let clients think about it.”

Manzella believes that there is less call for large commercial recording rooms. “More and more stuff is being done in alternate venues, and with alternate methods,” he says. “There are less and less commercial, large music studios, and more private- or producer-based studios, in my experience.”

But as he also reports, “When we get a call about doing an old-school, large recording studio it’s actually very exciting, because over the past five years I’d say that that kind of work has dwindled.”

Large rooms are not entirely going out of style, but multiple large rooms are certainly a rarity. “Even some really large projects that 10 years ago would have involved multiple large music studios are now looking at one large music studio and multiple supporting smaller studios. Because it seems that’s where the income really makes sense—in a smaller capital outlay, in a smaller billable nut.” Those smaller rooms might be a modest-sized control room and a booth, says Manzella, “But there are a lot of guys who are looking to make a long-term commitment to a space like that.”

Such arrangements can be mutually advantageous, he continues. “If the facility provides a lot of rooms like that they can look at multi-month rentals, or multi-year rentals in some cases, from producers and engineers who just need a place to do their day-to-day work. And when they need to cut tracks, they either book that big central music studio or they go to another place. So if there was an overall observation about the business that would be it—less big rooms, more multiple small-room facilities.”

But Manzella has been building more and more post production rooms of late: “Because post production is strong, and it always will be strong. There will always be a need for audio for video, and whether that’s our network clients, or whether that’s private post houses, we have done more and more of that kind of work.”

Cox agrees that multiple room facilities are now commonplace. “Even the private projects will have two rooms, with a primary plus a secondary writing room or production room. Most projects these days, the client will write, mix and it’ll be on the market in a calendar month, so there are a lot of people working with them,” he says.

“In room integration I always try to give everybody everything they need, and stuff they think they don’t need but end up using. You can easily set up people around the room and they have everything they need on a local panel, so editing can be done on the fly at stations around the room. It’s everyone on laptops, networked in.”

Of course, just because someone has a well-designed room full of high quality equipment doesn’t guarantee that the results will necessarily be great. “It’s what you do with it,” says Cox, who believes that education is an issue. “A lot of the schools have great equipment. But there’s also an increase in recording schools that are just laptop-based.”

The topic is one of his soapboxes, Manzella admits. “Everybody’s got all of this great equipment, and this equipment is capable of making great sound, but you have to know what it’s supposed to sound like. You have to have a reference.”

Manzella’s frame of reference comes from what might be considered a golden age of analog recording. “I’ve listened to a lot of older stuff and I know what it sounds like. Every once in a while we’ll stumble across a new record that we think sounds good, but they’re few and far between, unfortunately.”

But in a new world of mp3 files and the loudness wars, “I’m sure we’ve raised a generation, maybe a generation-and-a-half, of engineers who don’t know any other way,” he believes. “They just don’t know that there was another way that this used to be done.”

Perhaps the resurgence of interest in analog equipment will see a return to good engineering practices. Cox is optimistic, at least: “It does seem that the newer generation of engineers seems to care about how things sound,” he says.

Lachot is optimistic, too, about the direction in which the business and the economy are moving, and about the level of optimism in the industry. “The music business took a pretty hard hit during the years when the economy was tanking. But especially at the trade shows recently, AES and NAMM, I felt like there was a lot of optimism,” he says.

“I feel like people’s ideas of the future have improved. We have a strong business, and a lot of people talking about building studios.”