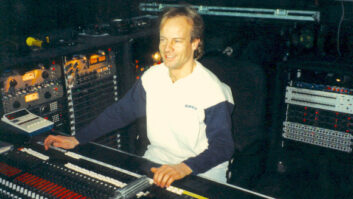

Ron McMaster’s life has come full circle twice over, intersecting in the intimate setting of the George Augspurger-designed room he has worked in for almost 30 years at Capitol Mastering. First, the resurgence of vinyl has made Capitol’s sole disc-cutting engineer as busy as he was when he started cutting lacquers in the 1980s. This past year, he worked on a project he never would have dreamed of doing for Jack White’s label, Third Man. Namely, he got behind his lathe and cut lacquer for songs he recorded at 19 years old with his band Public Nuisance, for an album that got shelved and forgotten by the music industry 40 years ago.

Formed in the mid-1960s, Public Nuisance was a garage-rock band McMaster started with his high school friends in Sacramento, Calif. They toured mostly in Northern California, playing shows with such bands as The Grateful Dead, Buffalo Springfield, Janis Joplin and the Doors. In the late ’60s, they signed to Terry Melcher’s Equinox label and cut a record with famed producer Eirik Wangberg. Public Nuisance seemed to be heading toward success, until the Manson murders altered their course.

“The story goes that Charlie Manson was trying to get signed to a record deal,” McMaster recalls. “Terry turned him down, and it really ticked him off. So Manson wants to go to his house to take care of him, but he was no longer living there. Manson goes in and does this terrible thing, it freaks Terry out, and he just dropped everything. We were on the desk ready to go, and everything just stopped.”

The band broke up and in 1971, and McMaster moved to Los Angeles to become a session drummer, working by day with an engineer at Sound Recorders. “In those days, studios of that caliber all had a disc-cutting room,” McMaster says. “That is when I first discovered disc mastering and what it was all about. When I had some free time, I’d go watch him cut records and just really thought it was fascinating how he did it, and the variety he got in a typical work day. He would do a rock album in the morning and a Hawaiian album in the afternoon. I wasn’t the type of individual who could be in the same room for three or four months with a band. That didn’t interest me. This interested me because of the turnaround and the variety and the challenge of getting the recording from tape onto disc.”

So McMaster began to pursue an engineering path more seriously, getting a job selling tools during the day to pay the bills, and spending his nights at A&M Records being taught the craft by a friend who was a disc-cutting engineer at the label. He landed his first job as an engineer at United Artists working for Dino Lapis, and then moved over to Capitol in 1986.

Public Nuisance and the record they recorded remained a distant memory until early 2000 when a tiny label called Frantic got hold of some of their material for a “Best of Garage Bands in the ’60s” compilation and released a full-length album of their songs. The CD sold a few thousand copies, then went out of print. Almost a decade later, Jack White got his hands on a copy and began tracking down the members of Public Nuisance. He signed the band, released the album, and gave Public Nuisance a long-awaited chance in the spotlight. Of course there was only one person to look to for mastering and cutting the lacquer for the aptly titled Gotta Survive.

“Part of this deal was that I didn’t want anyone else cutting this record,” McMaster laughs. “I had all the master tapes at home, so I said I would do it and I had the experience of being my own worst client! There are some people who will just labor over something, and now I found myself doing the same darn thing! I was in here all day cutting my own parts. And I had a blast doing it.”

The album was mastered directly from the original 2-track analog masters using essentially the same tools, updated with modern mastering elements. The tape machines he uses are a Studer A-80 Disc Mastering machine with ¼-inch and ½-inch head stacks, and an ATR 4-channel machine with ¼-inch and ½-inch head stacks. Signal is passed through a Capitol/Neve custom mastering console with dual Neve 1081 mastering equalizers and the custom-built Capitol 5511 tube limiter compressor. The lathe is a Neumann VMS 70, installed in the 1970s at the request of the Beatles. “The story goes that when we ended up cutting a lot of Beatles stuff here for America, they wanted to cut on the same lathes that were being used over at Abbey Road,” McMaster says.

Capitol Mastering has a long history of quality vinyl mastering, with the first stereo disc being cut by EMI engineers on an in-house system built in 1933 and the Neumann lathes housed at the Tower in Hollywood, which have been running since the mid ’50s. Cutting lacquer is an artisan’s craft that takes years to master, and depends on a refined skill set that incorporates musicality, precision skills, math and science. Possessing all of this, McMaster has been a key player in maintaining Capitol’s stellar vinyl-cutting history.

“I do the best job I can, keep the music as transparent as possible and make it sound as good as it should,” McMaster states. “People come here because they like the warmth of the room, and they like the sound I get out of it. I’ve been here a long time, and I can work this room pretty good.”

The landscape of the Capitol Mastering is again shifting to answer to the increase in demand for vinyl products. Another Neumann lathe is being pulled out of storage, dusted off, and set up in an additional room dedicated to mastering and cutting discs. The demand for McMaster himself continues to increase on a daily basis.

“It’s a pretty narrow field I am finding out as I get older,” he says. “There are not many of us around that do this. Now that it’s got this second life, all of a sudden I’m busier. I feel like I got my old job back. I’m even training someone new, and it is working out great. I am so happy because I wanted to be able to pass this art on. It was bumming me out that it looked like there wasn’t going to be anyone here to take this over. So I am getting great satisfaction out of the fact that I am now able to pass on this craft.”

With this veteran engineer “getting his old job back” and Jack White helping him to realize a youthful dream he had long given up on, the most important message to take from the changes and rediscoveries over the past few years is clear. “My new mantra is ‘never give up,’” McMaster says. “I tell all my clients and friends that if I can be in my 60s and be signed to a record deal for something I did when I was 19, there is always hope at the end of the tunnel.”