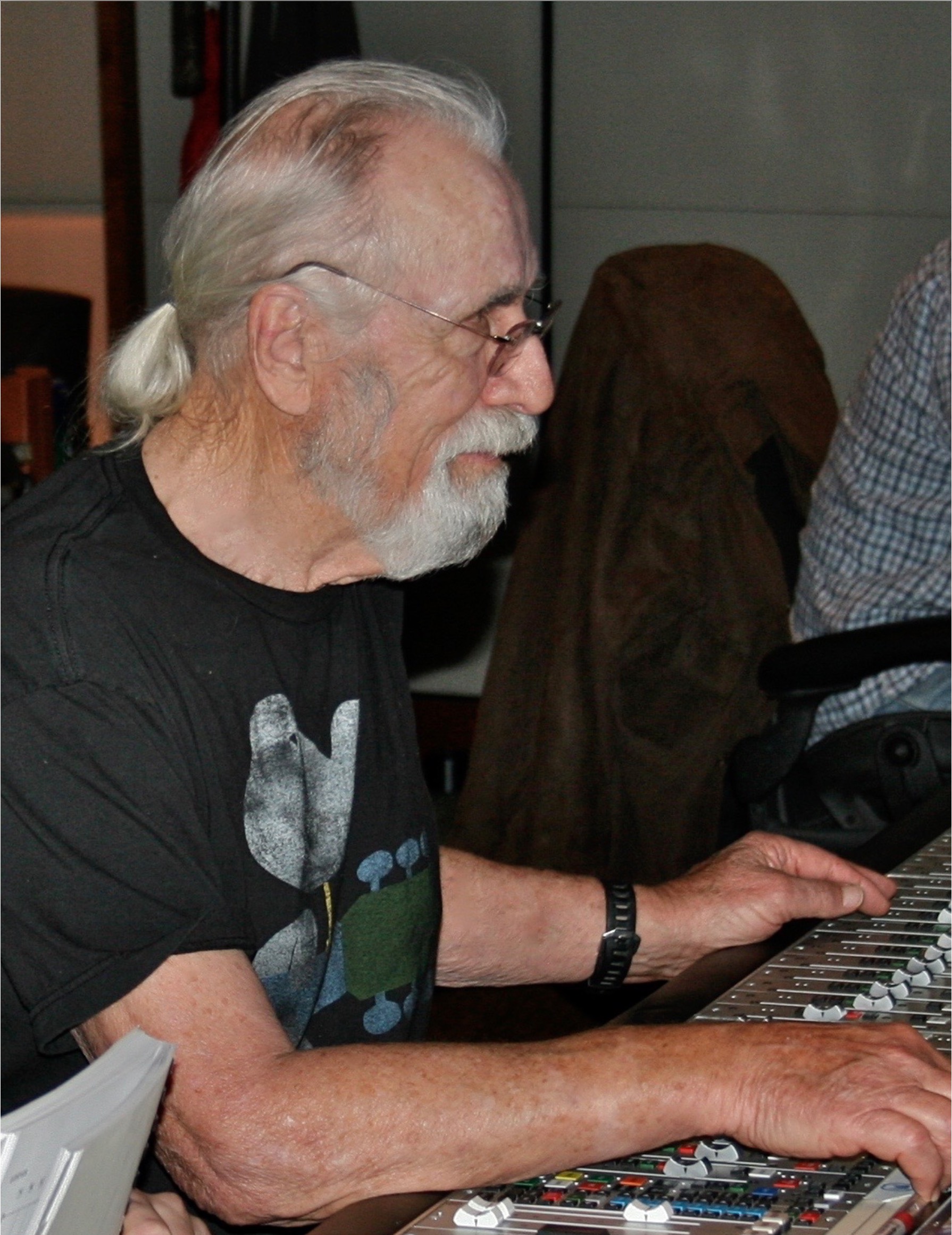

Now retired, following one of the longest and most successful careers of anyone, anywhere, in audio engineering, Dan Wallin, or Danny, as his neighbors and friends call him, sits with his hair pulled back in a salt-and-pepper ponytail. A breeze carries through the house, the sound of the ocean a constant presence no more than 20 feet away from the back door of his Hawaiian home. It’s been six years since he stepped away from Hollywood, and Wallin now enjoys his days with his wife, Gay, and their two dogs. Life is good, indeed.

The wall on one side of the living room, where most keep a shelf of their favorite DVDs, sits a library of classic films and CDs, all of which Wallin recorded and mixed. His contribution to music and film cannot be overstated. As a body of work, it is truly overwhelming, a reflection of a remarkable audio run.

Wallin’s career in audio began about six months after leaving the Navy at the end of World War II. After passing his general radio license tests, he got his first paying network job at ABC. He watched and learned within the industry from its beginnings, ganging multiple mixers together for 1940s big bands, on through the digital punch-in, punch-out, plug-in world of today. He considers himself fortunate to have worked “during the good days.” To him, they were all good days.

During the 1960s, Wallin worked in a number of jobs around Los Angeles, one of them being “a dubbing and mixing house,” where he learned “the fade-in.” “Those guys over there really knew what they were doing and taught me all kinds of mixing and dubbing tricks,” he recalls. “In those days, most television shows and movies were still done in mono. So in order to do a perfect fade-in, you take a cloth wipe with some acetone on it and find where you want the fade to end. Then, you lightly wipe and drag back towards the beginning, wiping it clean at the off point. That was done all the time in Clint Eastwood films and most Westerns.”

Though IMDB lists Spartacus in 1960 among his credits (uncredited), Wallin’s career in film music tracking and mixing, and re-recording, really began in 1965 with the score for My Blood Runs Cold. When he signed out in 2013, after contributing to Star Trek: Into Darkness at age 86, he left a legacy of more than 500 films, to go with countless music projects, including two Grammy Awards for Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media, for Pixar’s Ratatouille (2008) and Up (2010).

Whether as music recordist, music scoring mixer or re-recording mixer, Wallin’s six decades in film music have provided the soundtrack to at least four generations. Just a partial list: Bonnie & Clyde, Cool Hand Luke, The Wild Bunch, Dirty Harry, nearly all the Star Trek films, Stripes, The Right Stuff, the Roots TV miniseries, The Karate Kid, The Fugitive, Mrs. Doubtfire, From Dusk Till Dawn… The list just keeps going.

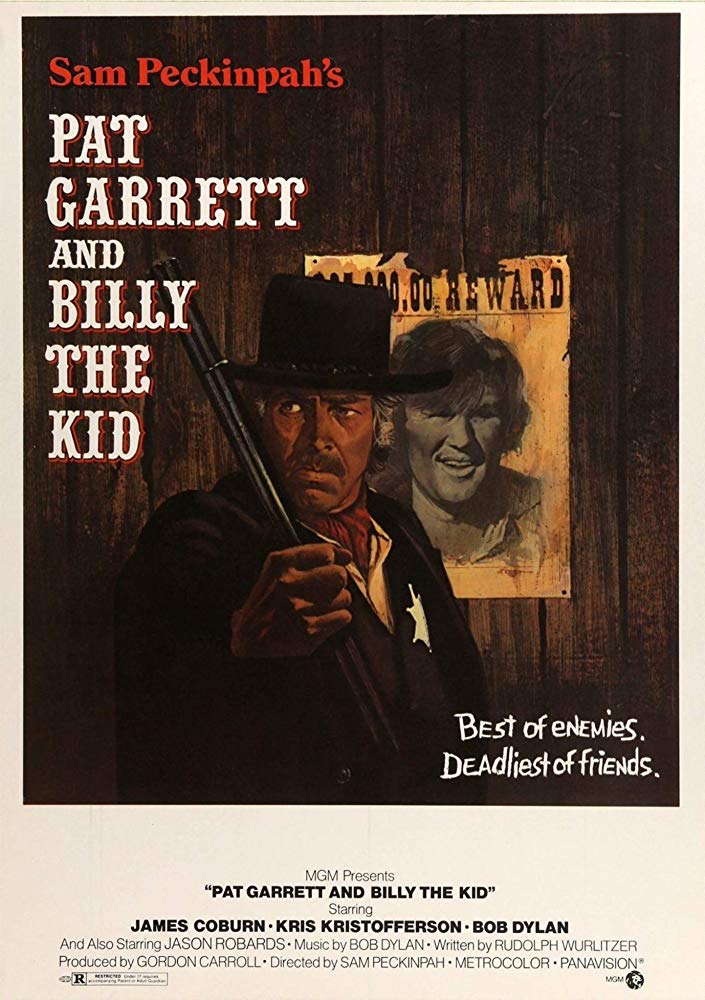

One of those films was Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973), featuring a soundtrack by Bob Dylan and the debut of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.”

“He’s an interesting guy, a really neat guy,” Wallin says of Dylan. “I was in the [Warner Bros. scoring stage] setting up when he got there. He walked in through the doors and kind of slowly walked in, looking up at the ceiling. Then Bob said, ‘Wow … big room. I laughed and said, ‘Well, don’t worry, we’ll cut it down a little for you.’” Wallin was in the film business. It was a big room for a big song.

“Bob wrote the majority of that song sitting in front of me, occasionally smoking his brass pipe, and then we recorded it.” Wallin recalls, commenting that the session was loose and all around. “The guitar player was missing a finger, and the band was missing a keys player. We had to hire the contractor, who played a small pump organ to fill in. The vocals were recorded with a pair of Neumann U67s—one for Bob and one for the backgrounds.”

Related: Using Leakage to Your Advantage When Miking an Orchestra, March 10, 2009

When he had the option, however, Wallin preferred to record vocals with a favored Telefunken U47. Capitol Studios owns five of them; Wallin likes the one marked #5. There is just something that was sonically different about the way it captures the voice, he says, and whenever he was working at Capitol, he always used #5.

Miking and Mixing

All engineers have preferred setups, and the best are adaptable to change if the situation calls for it. Once Wallin and I started talking about some of his classic films, we veered off into some of his classic techniques. It was an afternoon of pure education.

If there was no U47 to be had, Wallin went to the Neumann M49, which he says is “the closest you can get without choosing between a car, house down payment, or a microphone.” Harps and woodwinds were miked with a Sennheiser MK40, and brass with a Neumann TLM 170, though the 193 is better, in his opinion, for recording trumpets and trombones.

Piano is miked the same way every time for his recordings. It requires a matched pair of Jubilee Neumann TLM 170s placed and angled so that when the player moves a hand across the keys, the instrument moves across the sound stage in a beautiful stereo image. It’s the most difficult instrument to record but the most rewarding when you get it right, he says. Acoustic guitar is less tedious, and in the early days was miked with a U67, though he now prefers the TLM 170 on acoustics. Fretless, double basses sound best when put through a 193 or TLM 170.

The TLM 170 kept coming up, and when I asked him what microphone he would choose if he could only have one microphone to record with, he replied without hesitation: “The TLM 170.” The reason, he says, is its transformerless design; when the signal goes through a transformer, “there is an inevitable amount of phasing, which will frustrate you in the mix later.”

Related: Two Ways to Look at the Score, by Gary Eskow, Dec. 9, 2015

For miking drums, there are more opinions than there are drummers. For Wallin, with more than 70 years of first-hand experience with orchestras and drums and percussion of all types, every drum track starts with the kick. He uses a Shure SM7 pushed into the kick drum’s sound hole, angling it slightly away from the snare in order to minimize the inevitable snare bleed in every mic in the room. Sometimes he moved the sandbag in the kick closer or further away from the drum head.

The snare was also done very simply, with a single Shure SM57 on the top. No mic in the bottom? “It just creates problems in the mix,” he says. “You don’t want intermodulation, which is why when you do your overheads, you put them right over the drummer’s head. I use a pair of Jubilee TLM 170s and I try to get the capsules at a 45-degree angle to each other. You want to get them as close as you can without touching. When you space them out, you get problems as well, I find.”

The toms were always miked with an SM57, again pointed away from the snare. A KM84 was always used to mike the hi-hat, and it, too, was pointed away from the snare.

The Room Matters

But it’s not just about great-sounding microphones. A lot of pieces go into creating a recording that will stand the test of time. For Wallin, 30-foot ceilings and a Neve 88R with Flying Faders are usually a good place to start.

His favorite room to mix in was at Warner Bros. The setup was great, he says, and so were the people. The tracking room at Warner, while not his first choice, was excellent and gave the brass recordings an extra punch. The best room to track instruments, in his opinion, was Sony (formally MGM). “Sony was great until they installed the air conditioning,” he laments. “The reason the air conditioning was a bad idea was that, first of all, the musicians hated it because the stringed instruments went out of tune all the time. The other reason was that the square edges were terrible for acoustics.”

Related: Solid State Logic Duality Console Centerpiece for L.A. Sound Gallery Studios, Nov. 5, 2008

Wallin grew accustomed to recording in the world’s largest, best-equipped studios. So when I asked him about the smallest room he would ever want to work in, he paused a minute to think, then said, “Capitol A.”

“But the size is less important than measuring and eliminating standing waves,” he continues. “It’s not hard to find them with equipment, and it’s easy to fix them. I was over at A&M one time helping a friend record a score, and he was having trouble with the presence in the horns. So I said, ‘Well, let me go out there and have a look.’ So we walked around and had a listen. Then we found where he thought the problem was, and we dragged two big 9-feet-tall gobos over to the spot near the entrance door. He put them together and angled them a couple different ways, and then suddenly the horns were there with all this new presence.”

Want more stories like this? Subscribe to our newsletter and get it delivered right to your inbox.

Those days are now behind him, but Wallin is completely at peace in his Hawaiian home, a beautiful place that is exactly what you would expect if you’ve had the pleasure of meeting him. The garage is a woodwork shop with speaker parts and circuit boards all around, all with a story behind them. He maintains that Depression-Era work ethic: If you need or want it, then learn all there is to know about it and make it yourself.

It’s not surprising, then, that now in his 90s, Wallin has made a side business out of hand-making some of the best mixing monitors in the world. After ten years of design work that started 15 years ago, he has perfected both his two- and three-way designs. His speakers can be found in many of the top studios around the world, including Disney’s Pixar and Warner Brothers.

One of the most important differences in his speakers over the competition, he says, is that his don’t have a spider, which produces sound that is distorted and is mixed in with the sound of the cone. The clarity is therefore limited by its own design. Wallin’s speakers are superior because of a ferrofluid suspension design, rather than the spider. The result, as I listened to a few playbacks, is a crystal-clean image that is as fantastic to be around as the guy who made them.