You should not be afraid to not be logical.”

These were Denis Villeneuve’s first words to supervising sound editor Mark Mangini upon embarking on the first stages of designing the sound for Blade Runner 2049. “Denis is one of the few truly forward-thinking directors who understands the importance of sound and its ability to inform the edit and tell his story,” Mangini says.

To that end, the director was quite prescient in bringing on Theo Green to work with him and film editor Joe Walker in Budapest during production. Green, an accomplished composer, had worked with Walker (and Blade Runner 2049 co-composer Benjamin Wallfisch) on the 2008 film The Escapist as sound designer.

Green says that “Villeneuve had long wanted to start the sound process at the same time as shooting the movie and bring picture and sound together. It’s difficult for the producer and director to preview a scene with a flying car and not have anything custom-built to go with it. Normally, an editor would pull something premade from a sound library. But when you have this sort of ‘world building,’ in a movie with fantastic elements, Denis thought it made a lot of sense to have the sound design process start early and get a taste of what things would sound like while they were still shooting.”

Once production had wrapped, Mangini joined the film the first week of January 2017 as supervising sound editor. He spent several months in the early stages endeavoring to realize the director’s goal of “composing with sound.”

“Theo and I were working together in those early months without any deadlines, divvying up projects, going back and forth with Denis and Joe, making presentations and building a sonic environment that was musical—but without melody,” Mangini says. During this phase, Dave Whitehead, designer of the “heptapods” from Villeneuve’s 2016 film Arrival, came on to help with those musical textures, as well as create early mockups of spinners and the Pilotfish.

In late March, ahead of the first temp dub, Mangini brought on what would become the remainder of the sound editorial team: designer/editor Chris Aud, editors Lee Gilmore and Greg ten Bosch, with Ezra Dweck supervising the Foley. Mangini viewed the collaboration of the team as a post-sound version of what has become known in television as a writer’s room, running the film over and over and spitballing ideas.

“Each one of these editors is a ‘designer’ in his own right,” Mangini explains. “Lee, Chris and Greg all created an enormous library of new and designed sounds on top of their more sundry chores editing reels. Chris Aud, in particular, had the enviable task of designing almost all of the sounds of the spinners. Another vital contributor to the track was Charlie Campagna, who did a lot of effects recording, sound design work and effects editing.”

Mangini also did a considerable amount of effects recording, both on his own and with colleagues Ezra Dweck and Eric Potter. He lucked out. The movie takes place in the midst of constant rain, and Southern California, when he started on the film, had one of its biggest rainy seasons in history.

NODS TO THE ORIGINAL 1982 FILM

Given the prominence of advertisements playing throughout both Blade Runner films, Green, effects re-recording mixer Doug Hemphill and Mangini took effects recordings of alarms, police car sirens and klaxons and played them through speakers in an empty Stage 22 on the Sony lot. Green says that they played some material back at twice-speed and then pitched it back and time-adjusted to correct it. The result, he says, was “as if you recorded it with a speaker that becomes twice as big. Sometimes we’d mix back a little bit of the original.”

Mangini wanted to acknowledge the first movie, but not copy it. “Vangelis had these lovely bell chimes that I couldn’t quite put my finger on,” he says. “I didn’t know what he used. I found some wind chimes that had some modal intervals; they weren’t the usual major-key ‘happy happy’ chimes, and I took those and twisted them with processing and that becomes what you hear throughout the Wallace corporation, the casino and Freysa’s basement.

“The things that the [sound effects] guys excelled at was stuff that seemed simple but was not,” says re-recording mixer Hemphill. “Theo cut in some little squeaky thing right before K [Ryan Gosling] freaks out and throws the chair, and says ‘I know it’s real.’” Hemphill notes that, for the Deenabase device that quite intentionally looks like a Moviola, the sounds were “really delicately layered. The same when Coco is going through the box of bones—there’s all those sounds of lenses changing and focusing. They did a beautiful job; it’s just crazy.”

As he has for the past seven years, Mangini chose to have the Foley done by Andy Malcolm and Goro Koyama of Footsteps Studios outside of Toronto. While Malcolm’s protean Foley skills have been renowned for decades (he made the famous split-screen film about Foley, Track Stars: The Unseen Heroes of Film Sound, back in 1979), since 2000 he has been known for having his whole house wired for sound, allowing for more natural perspectives and acoustics. Footsteps also has two more conventional Foley studios built to simulate dead exteriors and for water pits and the like.

As much as his home and studios give him flexibility with acoustic spaces, Malcolm and crew often do “on-location Foley” with a portable rig. For Blade Runner 2049, he found a lecture hall in a nearby town that doubled for the Wallace Corporation interiors. Mangini says that it all sounds “delicious and beautiful.” For the crash of the spinner in the Trash Mesa, the Footsteps crew went to a scrap yard to record automobiles dropped on top of each other by a crane.

While location effects recording in such venues is SOP in film sound, Mangini asks, “How many Foley studios do any of us know that would go to such lengths to create something as believable as that. The status quo would require that the Foley artists find some way to simulate this with a small prop and make it work with some manipulation. Why can’t this be Foley?”

Supervising the dialog, principal ADR and group ADR was Mangini’s longtime colleague Byron Wilson. “Supervising” the dialog team in modern film sound post-production often means, even on simple films, being the head of a passel of editors. However, for BR 2049, save for a few weeks of work by others, Wilson was the sole sound editor for ADR and production dialog.

Due to the extreme set noises, Wilson and dialog/music re-recording mixer Ron Bartlett had to work hard with Izotope noise reduction to get many scenes to play, and as a result there was much less ADR than one would expect.

“I also do a lot of de-crackling and spectral repair, et cetera, before the tracks get to the stage,” Wilson explains. “I present a balanced and phased boom vs. lav for the tracks to have the correct resonance and matching of reverb. Many scenes are both boom and lav used throughout. If I think only one track is the way we should go, I mute the other but leave them on adjacent tracks if we want to check them out. My view is that you should hit play and have a movie.”

One of Wilson’s challenges was to infuse the world of Blade Runner 2049 with the same polyglot feel of the 1982 film. He and his loop group supervisor, Caitlin McKenna, recorded Japanese, Korean, Hindi and Russian voices for the advertisements that play throughout the film from billboards and vending machines. A gumbo of languages can also be heard from the scavengers when K crashes in the garbage dump that was previously San Diego.

RE-RECORDING, VIRTUALLY

Blade Runner 2049 was mixed at Sony Pictures Studios in Culver City, with the temp dubs done at the Cary Grant Theater and the premixing, final mixing and versions at the William Holden Theater.

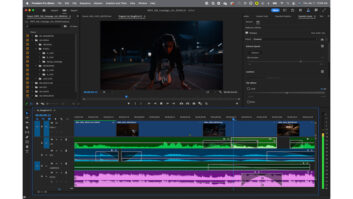

Re-recording was all done “virtually” in Pro Tools, per the directive of Bartlett, Hemphill and Mangini. “I had made it crystal clear, from day one of my involvement in the movie as I was preparing budgets,” says Mangini, “that the only way I could be involved would be if we could mix virtually in Pro Tools.”

As it turns out, Sony had recently installed Avid S6 control surfaces in the Cary Grant, and when the team moved to the Holden, S6s were unceremoniously dropped on top of the resident Harrison.

Wilson says that the idea of mixing in the legacy workflow of recording premixes and then doing the final mix from them, with consoles and outboard equipment in the middle, “would have been difficult here. I feel that the way this allows temps to progress and become the final mix is essential. Filmmakers justifiably have the mentality that once you do something, it’s done. It should be ‘like that, but better.’”

Mangini maintained two “god” Pro Tools sessions that went to the stage for each reel, one with hard effects and Foley, and the other with backgrounds and sound design. While it might have been possible to combine them into one, he feared that he’d be pushing the DSP limits of a Pro Tools HDX-2 system. Similarly, Wilson was in charge of the master dialog session, while the score was handled by music editor Clint Bennett.

The premix period of Blade Runner 2049 was 20 mix sessions, with seven of them done in double shifts. The final mix at the Holden lasted a total of 19 days, broken into three periods, each followed by review screenings and fixes. The first pass on the final lasted nine days, approximately a reel a day. While this is a fairly normal rate, the schedule originally assumed a six-reel film.

Only a few days from the end of the final mix, Mangini was notified by the legal department that they were not able to use any “unlicensed” sound effects or music from the original film. (One sound effect did in fact remain, the iconic tone in Deckard’s apartment that had originally been created by Ben Burtt for Star Wars and co-opted for Alien, and was then re-used in the original Blade Runner. Because Burtt owned the sound, its origin was not from the first film, per se, and so it was allowed to be in BR 2049.)

Problematically, Mangini had created updated versions of the Vangelis deep drum hits that open the first film, in 7.1, and they had become the cornerstone of the mix. “I reprised them in the film and used them not only as chapter markers, delineating cuts between important scenes but also to ‘sting’ important dramatic beats,” he recalls.

Concerned about copyright infringement, Mangini called the “resident percussionist” of the team, Bartlett, at home and asked him if he could whip up some replacements in his home studio—that night! Bartlett said, “I’m on it!” and went into his studio until three in the morning, giving them to the music editor Bennett in the morning. All of the booms that are in the final film were done in that session, and Mangini thinks they are even “bigger and better” than the originals.

VERSIONS, VERSIONS AND MORE VERSIONS

Blade Runner 2049 was released in every stereo sound format known to man and engineer, and required extensive stage time to create the “versions.” (Bartlett says that the one format that they didn’t do was Academy mono.) After the final mix, it took six weeks to record all of these formats and their respective M&Es. Perhaps it’s more clear to say that the versions took much longer than the final mix itself, and the crew was unanimous in their opinion that this reformatting took time from the creative work during the final mix. Hemphill says that during less than a week of fixes during finals, “The mix got 35 to 40 percent better. We had serious regrets that we had to stop this and start making the versions.”

The Atmos printmaster was effectively done when the final mix ended, given that they were monitoring in that format the whole time. The first and perhaps most important iteration was the 7.1 and 5.1 fold-down, incorporating the objects and overhead channels into the standard screen and front speakers. Bartlett says that “while Dolby offers a tool to do 7.1 re-renders [in the Dolby Atmos RMU], Doug and I feel that a hand-crafted approach yields a superior result. We rendered out all the objects and panned them to where they were supposed to be and used all of these elements to make a 7.1 mix. I think it turned out really well. There are aspects of the 7.1 mix I like even better, but as a whole I like the Atmos better because of the full-range surrounds and the space with the speakers in the ceiling.

“Sometimes the panning is different, or the speed of it is different,” he adds. “That was the big thing: not just where it was supposed to go, but also at the same speed. Something might travel down the wall different, especially with Doug. With music, which is more atmospheric, you’d say, ‘Did that go too far back?’”

Viewing the original 1982 film today reveals a remarkable blending of sound design and music, and indeed much of what we think of the province of the sound effects department was created by Vangelis. The sound team of the sequel 35 years later flipped the script here, and on the specific encouragement of their director, were asked to be composers with sound. Villeneuve insisted that the “billing block” section of the main-on-end titles include a single card credit for Mangini and Green, right up there with the composers and cinematographer, proclaiming to the filmmaking community and the public that “Sound Is Important.”