It wasn’t too long ago that videogames represented an interest of less than 10 percent of the nation’s population. That meant if you sold 1 million copies of a game, you were wildly successful. A handful of developers created games that were this financially successful, one of which was Wing Commander, released in 1990. Not only did the game sell well more than 1 million copies, but it also represented the first time a game programmer (Chris Roberts, who was also the game’s designer) went on to direct a feature film. One of Wing Commander‘s most notable aspects was its soundtrack: A groundbreaking leap was taken in cinematic presentation, and the soundtrack followed suit with a John Williams/Alan Silvestri-inspired score that made players’ jaws drop, especially on high-end sound modules such as the Roland MT-32.

Team Fat — headquartered in Austin, and run by George Sanger, aka “The Fat Man” — composed the game’s music. Team Fat went on to compose scores for more than 200 games and became the best-known music team in the gaming industry. I caught up with Sanger to find out what he’s up to, and discovered a remarkable approach toward music and recording that is refreshing in today’s ideal of “more is better.”

You’ve been making music and sounds for games for 25 years, and you’re one of the most unique personalities in game audio. Tell us a little about yourself.

We’re all unique — that’s what makes us the same. [Laughs] But I think what makes me different is that I look at the large, pristine, groomed studios loaded with neatly stacked gear and it speaks to me of fear. I picture — especially in game companies — the foreign shareholders being paraded through the studio, and if it has the wrong kind of wood paneling or doesn’t have one of those acoustic baffles that look like a city made out of blocks — if it doesn’t look “real” — then they might not invest in it.

For me, I have this mental picture on the cover of Cosmo’s Factory by Creedence Clearwater that shows kind of a garage studio. I said, “That’s the way to make music.” A combination of that and the big rooms in the Let It Be movie, right? Somewhere between those two things, where you make noises and there’s a tympani on the wall and a closet full of percussion instruments. I assumed with the explosion in home recording that there would be thousands of places like that creating music like that. For some reason, it short-circuited somehow, where people with the home studios tend to make fairly dance-oriented stuff and it tends not to get into games or films, and it didn’t turn out the way I thought.

To me, the equipment and the room are to make something of the expressions that come from within. And even if it’s not deep within, it’s something that is at least fun. Or in the case of a game, something that is warm or good or appropriate. The playfulness of it is where the art and beauty are.

It comes down to peek-a-boo. The only reason we play, or come to this planet for that matter, is experiencing fun moments that we tend to call art, but it’s essentially sophisticated peek-a-boo. An expectation is set up, and it is either filled or it’s not. Marty [O’Donnell] in Halo 3 gets extra points for using synths in Halo that some folks might consider “outdated” or “not orchestral,” or whatever the current “safe” fads are in soundtracks instrumentally. Because people expect unexpected things from me, I need to tear some new buttholes these days. So I tend to like something more like Beck or The Beatles, in the context of what went before them — something scary to listen to.

Switching gears, what do you think the minimum level of interaction a composer or sound designer should have with a game?

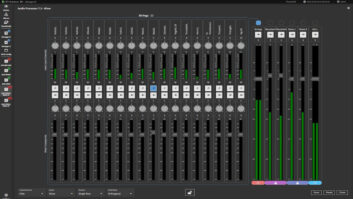

I start with my creatively encouraging rig, and it’s clear to me that I can sit in that rig and make great noises that will sound great in the game. If you get things too complex, you drift away from that, from the peek-a-boo. When you sit down at a piano, you start banging away and eventually perhaps create a melody. If you sit down at a synth, you may begin to play with patches and envelopes. If you sit at a computer, you may just start surfing the Web. The last two things don’t yield a melody or something you consider cool.

Just the same, mapping sounds to an environment in a game is many layers away from a great moment in the game that could either derive itself from music or sound, an audio “joke” or something that creatively explores new ground. I’m a little bit closer to being in touch with the idea that I’m going to make a noise, listen back again, and say, “Wow, hah! That’s cool!” The best tool that I work with right now is for the slot machines that Dr. Cat put together for me awhile back, and it is basically a text file I edit in Notepad. Parameters are controlled such as panning and looping when a sound plays. This allows me a fast way to map sounds into the game, and I’ve done a couple hundred games that do that and it is very efficient. The most important aspect is that there’s no programming involved. I’m trying to get Full Sail to teach this as an absolute minimum for when someone designs a game, not necessarily a standard.

If you don’t have something like that script or better, you’re in the position where your programmer has basically forgotten about anything that might be complex, subtle or interesting about audio, and has mapped one action to one WAV file and named the WAV file after his favorite science-fiction character. So you load the game and it plays “Borg.wav.” What you’ve done is you’ve shot to hell your ability to adjust volume, to use more than one sound for a given event, to track your file version because everything will have to have the same name and you can’t hear it until you ship it off to him and bother him. He’s dug himself a hole in which he’s going to be bothered by you, the “sound guy.”

What was your first game?

It was Thin Ice by Intellivision. We just played the theme at a Classic Gaming Expo in Las Vegas. It just got posted to YouTube [at www.youtube.com/watch?v=2O5YB5RFC0c].

I saw that — you rigged a keyboard case as your kick drum when it didn’t show up and used a cell phone delay for the guitar delay!

You can have your readers watch that. That’ll confuse ’em. “Surf music? What the hell!”

I have to admit, interpreting game music as a surf band was a little confusing when I first saw it years ago at the Game Developers Conference.

People would say, “What does surf music have to do with black T-shirts and pixels? This isn’t game music!” [Laughs] So, good. I always took my eclectic tastes for granted and assumed there were a lot of other people who wanted to make exciting and extreme stylistic combinations. Maybe I was gifted, maybe I was cursed. When I do it, it confuses the hell out of people. I just make any noise, any style, and try to make it impactful to the heart rather than in a specific style for its own sake.

These days, there isn’t as much experimentation in games themselves. People are making great games, don’t get me wrong, but the strokes aren’t as broad except in the indie, casual game arena. I want people to laugh so hard that coffee will come out of their noses. Games are no good if the increment between one and another is too small and safe. But if the increment is too great, there’s just as good a chance that the game will flop. People making games along those lines aren’t doing “wrong”; they’re being responsible. But I’m catering to people who can set their business up to be a little loopy.

Alexander Brandon is the audio director at Obsidian Entertainment.

READ:

Related Articles

The Fat Man and the Bar-B-Q

Mar 1, 2007 5:16 PM, By Sarah Jones

Recording Wild

Feb 1, 2007 12:00 PM, By Sarah Jones

FIDDLERS ON THE ROOF Last year was my fourth year working as a research SCUBA diver in the U.S. Antarctic Program. I was also moonlighting as producer,…