With his multi-Oscar-winning 2002 film Chicago, director/choreographer Rob Marshall showed beyond any doubt that he knows how to bring a stage musical to contemporary film audiences in strikingly creative ways. After a detour to Japan for the historical drama Memoirs of a Geisha (2005), Marshall has gone back to Broadway for inspiration, this time moving the 1982 hit Nine (a Tony winner for Best Musical) to the screen.

While perhaps not as immediately accessible to U.S. audiences as Chicago, which had the benefit of being a period American saga with music to match, Nine is actually a more interesting and compelling story. It’s based on an Italian play that was itself adapted from Federico Fellini’s classic semi-autobiographical 1963 film, 8 ½, about a filmmaker confronting a creative block and examining the many relationships with women—including his wife, mistress, a whore and others—that shaped his life. Fellini’s movie—and Nine—freely mix fantasy and reality, so Rob Marshall has a deep well from which to draw. He also has an incredible cast, with Daniel Day-Lewis—looking like a cross between Fellini and 8 ½ star Marcello Mastroianni—as director Guido Contini; fellow Academy Award winners Penelope Cruz, Marion Cotillard, Nicole Kidman, Judy Dench and Sophia Loren in some of the principal female roles; and Stacy Ferguson (Fergie), Kate Hudson and others. All the actors did their own singing (and dancing), and the film includes three new Maury Yeston songs not included in the composer/lyricist’s Broadway show.

It was music director Paul Bogaev’s job to prep the actors for their songs during the summer of 2008, and as is usually the case with these sorts of films, the songs were recorded before a frame was shot—in this case, tracking was mostly at Angel Studios in Islington, London, during September 2008. Comments executive music producer Matt Sullivan, who supervised the recording and also worked with the actors, musicians and orchestrator Doug Besterman, “It’s an old church where they’ve constructed three studios and we used Studio 1, which is a good-sized room, but it also has a lot of isolation, which for film, when you’re mixing in 5.1, it’s really important to have as much isolation as possible.” Studio 1 has a high-ceilinged main room and four iso rooms, all connected to a control room equipped with a Neve 88R console with surround panel and Meyer X-10 monitoring system. “Then, two of the songs were re-recorded at Abbey Road in the legendary Studio 2. We had two studios—2 and 3—tied in and a 55-piece orchestra,” conducted by Bogaev. Both Sullivan and Besterman worked with Marshall on Chicago, and Sullivan also was a music supervisor on three other recent film musicals: Rent, Hairspray and Dreamgirls.

“We worked with the actors and the dancers and the director,” Sullivan says. “Rob rehearses for a couple of months and we come in and shoot the rehearsals and the orchestrator comes in and sits in a couple of rehearsals. Rob is really great at telling everyone exactly how he sees a musical number. If he wants a song to be dark and dramatic and it’s Guido Contini’s wife feeling she’s alone and abandoned—he tells the orchestrator that, he tells the lighting people, and we’re all on the same page of what the feel is. When we see her on an empty stage with a single spotlight and you hear a single cello line playing along with her, it all works together. He’s very good at explaining his vision. In general, Rob’s approach to doing a musical on film is very much the same as doing a musical for stage. It’s just that our opening night is shooting it—and opening night takes a few months.” [Laughs]

Actually, Sullivan notes, “For the most part, it takes about two days to shoot one song; bigger songs maybe three days. A single person doing a song—like Daniel Day-Lewis performs this song ‘I Can’t Make This Movie’ that’s only about a minute-fifty seconds long—and that we did all in one day. But these songs are emotional arcs—it’s not like you do a verse and then it cuts to another scene and then you do another verse. These are all big performances and the actors usually like to do them all the way through, and there’s only so many times you want to force them to do the same thing. It takes a lot out of the actors.”

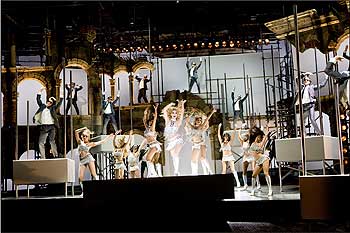

And even though the singers are lip-synching to playback when the film is shot, they are still singing every time. The combination of tight close-ups and skimpy costumes on many of the ladies conspired to make earwigs an impractical solution to playing the music on set, plus, Sullivan notes, “The dancers want to hear the big, loud music. We actually had a theater audio consultant come in and rig the entire soundstage, which is really big.” Most of the film was shot at Shepperton Studios near London, with additional work at Rome’s massive Cinecitta complex, and a little bit of exterior location work in Italy. Like the songs in Chicago, the ones in Nine make imaginative use of soundstages to create a sort of alternative stylized reality that is at once intimate and theatrical—in this case, the musical numbers are essentially in the mind of Day-Lewis’ Guido Contini character. No one is belting out tunes on the rooftops of Rome or on the Spanish Steps in this film, though in a couple of cases during a song, the visuals switch to the real world briefly. Where Marshall knew that he was shooting exterior elements that would be used in the body of a song, Sullivan says, “He might have the song in his headphones because the feeling and the tempo of the song will affect camera movements,” so when the film is edited all the material will fit together more smoothly.

This was also a major concern on the audio post side of things, notes supervising sound editor Wylie Stateman, who co-supervised with Renee Tondelli, working both in Hollywood and at Pinewood Studios (Shepperton’s sister studio) in London. “It’s the kind of film where dialog and music both have significant roles and the lines are completely blurred in terms of where dialog and music begin and end. The songs all have very significant dramatic meaning, so the dialog has to lace in and out of the songs, and there has to be great continuity in the performances, as well as the sonic transitions.

“Rob is very conscious about blending the musical numbers in a seamless way,” Stateman continues. “He doesn’t want the film to stop for a musical number; he wants the number to develop naturally from the emotion of the film. So as a scene is moving toward some emotional climax, the characters are driven to songs; they don’t stop to insert a piece of music. And Rob, because he has such great attention to rhythm and to timing, insisted that we carry seamlessly both the cutting patterns and the sound patterns—whether it’s the cadence in somebody’s voice or the cadence in their walk—to in a way ‘hand off’ to the songs in a way that minimizes the audience’s ability to foresee a song coming. Rob’s goal is to make the songs an organically evolved climax to the drama of any given scene.”

Co-supervisor Wylie Stateman roughing it on a soundstage

Stateman is a four-time Oscar nominee for sound or sound editing (including Marshall’s Memoirs of a Geisha); Tondelli is a dialog and ADR specialist. “Renee is such an important part of this senior team leading the sound work on this film,” Stateman comments, “because the dialog establishes a tremendous amount of the sonic integrity of the film, meaning acoustically it has to go seamlessly from spoken word into song and back out again, and that requires literally the micro-editing of the soundtrack. Sometimes things are blended syllable by syllable from production to ADR to music pre-record and then back again. She’s done an amazing job on this.” (The production sound mixer on the film was Jim Greenhorn, whose recent credits include such impressive productions as The Reader and Notes on a Scandal.)

Asked whether the early ’60s setting for the film required that the sound team go out and record a lot of period Fiats, Alfa-Romeos, Vespas and the like, Stateman laughs, and says, “That’s irrelevant to this film. It was a film that required a lot of original thought and very little original recording. The challenge for us was to keep the film moving through the songs, and to keep the emotion moving through the songs, and to connect all these these different pieces. There are 12 significant musical numbers, and that means so much of the film hangs on the integrity of those numbers. And the sound pressure of those numbers.” Sound pressure? “Volume—not just rhythm; and making sure that things are relative from a dramatic scene where it’s more classic filmmaking, to a more dramatic, highly choreographed scene that was photographed against playback. Again, you want it to be as seamless as possible.

“Foley was very important in this film,” he adds, “because it’s often Foley that ties the dramatic lensed material with the staged material against playback. We actually built a floor on the ADR stage over at Todd-AO on Seward in Hollywood and 12 dancers—some of whom had who had danced on Nine and some of whom knew Rob from Chicago—came in from around the world, and they danced these numbers wearing headphones and we made 5-channel recordings of their feet and of their movements. It’s a really a lovely contributing element making the playback tracks sound at home in the film and real in the theater.

“It’s not about covering everything; it’s really about finding the dramatic punctuation, finding just the right moment for a bit of movement of something to help with the perception of reality and the perception that these numbers were sung and danced in that shot.”

That particular Foley session was done in Hollywood “because it was more convenient for the dancers at that particular moment in time,” Stateman says. “I did it with Renee and with Harry Cohen, who was also a very significant player—he’s the sound effects designer. We’ve been together for almost 20 years; Renee and I for more than 10 years. We all worked with Rob on Memoirs of a Geisha. So Harry is doing sound effects design and Renee and I covered a lot of the other bases, with Rene doing the ADR and dialog, as well. Then, most of the rest of the [post] crew is British.” The film was mixed in Pinewood’s enormous, refurbished Powell Theatre (the largest re-recording studio in the UK) on the room’s Euphonix System 5. Mike Prestwood-Smith did the dialog; Rob Fernandez, from Sound One in New York, did music; and Pinewood’s own Richard Pryke (an Oscar-winner for Slumdog Millionaire) handled FX.

When I spoke with Stateman and Sullivan in mid-October, work had just begun on the final mix and neither was expecting any major problems to crop up. “It’s shaping up really, really well,” Sullivan says. “I’ve spent a lot of time in the last month getting the 5.1 music stems big and fat and punchy. My engineer that I’ve used for the last couple of years is Frank Woolf, who did Hairspray with me and some of Dreamgirls, and we mixed the stems at Westlake Studios on Santa Monica Boulevard. Then we came here and did some work at SARM Studios [in London], which is Trevor Horn’s place. We also did some fixes at Pinewood; some overdubs, some sweeteners—like, for this one song we really liked tremolo violins, so during scoring we brought in 12 violins and three violas to make that part more interesting.” Since the actors have long-since dispersed since filming, any vocal fixes that are necessary have to come from the multiple takes that were done for each song for the pre-records; again, not a problem, Sullivan says.

While the final was happening, Sullivan also had another task to supervise—the creation of the soundtrack album, which required a separate stereo mix. “We get the film into shape and then we use the 5.1 film mixes as a beginning,” he says. “We do some fold-downs, but that’s just the start—it’s lots of tweaking, tweaking, tweaking. You don’t compress the overall 5.1 stems, but obviously with the 2-track we do.” The soundtrack album was scheduled to be released the week before the film opened.

Meanwhile, back at the mix, the post team was hard at work finishing this film that Stateman calls “a crazy, beautiful canvas.” As a music man himself, and someone who famously works well with actors, Marshall is obviously very attuned to the importance and nuances of sound—it certainly says something about both his ears and his ability to hire a good sound team that both of his previous directorial efforts earned Academy Award nominations for sound (with Chicago earning trophies for Mike Minkler, Domenick Tavella and David Lee).

“Rob Marshall is a passionate, driven, detail-oriented director and he’s always looking to explore the depth of the emotion of every one of these scenes, and to keep it rhythmic and musical and flowing,” Stateman comments. “He’s totally the creative engine behind this film. He’s very willing to mix the soundstage with practical local shoots with different mixed media of color and black and white. He’s looking to create a film that’s unbridled by anything, and his imagination is quite vast. This particular film offered him an opportunity to explore both a ’60s style—which is really a tribute to Fellini—and today’s technology, in terms of digital negative-capture on film, finished with every electronic and digital advantage available. You can tell that Rob is still evolving as a filmmaker, learning every time he makes a film, and it’s been really exciting to make this journey with him.”