Remember the old saw, “Jack-of-all-trades, master of none?” Well, one spin through the reels of sound designer Tim Gedemer and composer Sophia Morizet proves the adage wrong. Indeed, the twosome — who work out of the Spank! Music and Sound Design studios in Santa Monica — can claim a credit sheet as varied as feature films, commercial spots and music videos, in a bevy of aural genres.

Morizet, who moved to Los Angeles from her native France in 1996, enjoys the diversity. “The purpose is always to prove yourself, trying to see where you can go and what you can do,” she says. “It’s putting yourself in danger — you can’t always write the same thing. You have your own recipes, so you’re going to pick up this kind of loop instead of this one. But, when the medium is different, it’s fantastic. What I like is that I’ve been able to push the edge technically and musically and play with both worlds. [For films], you want it to be cinemagraphic. When you work for commercials, you have to have something that’s extremely dynamic.”

Both Morizet and Gedemer came to the post world after dipping their hands in the music waters. Gedemer worked with a couple of rock bands in Los Angeles after graduating from college; Morizet started programming rhythms and synthesizers for a number of artists in France. “Most of the people that I know who do what I do are coming from music,” Gedemer says. “For whatever reason, we weren’t successful in the music business to the degree that we could make a decent living at it, so a lot of us turned our attention to doing sound for film. The process is very similar to composing — we look at a picture, we map out an idea or some kind of concept or feeling that we want to impart to the audience, and we bring that vision to life.”

Because Gedemer was familiar with the Synclavier, he broke in to the film world on the Roger Corman film Frankenstein Unbound in 1990. “I was an assistant editor that was called on to do a lot more than what assistants normally do,” he explains. His feature film credit sheet has expanded to include such films as Menace II Society, The Mask, Dumb & Dumber, Dead Presidents and the 2001 release From Hell. Along the way, he performed sound design work in a handful of specialty venues, which paved the way for his eventual expansion into commercials in 1998.

“Commercials are just very different,” Gedemer states. “You have to say what you’re going to say a lot faster than in film. Also, the expectations of the ad companies are quite different.” Gedemer began taking a more active interest in the commercial field as the spots were getting more sophisticated and required higher levels of creativity. He also expanded into music videos recently and has designed sound on videos for U2 (“Elevation”), Janet Jackson (“Doesn’t Really Matter”), Backstreet Boys (“Larger Than Life”) and Wu Tang Clan (“Gravel Pit”).

The Synclavier has been his main sound design tool, yet for the film From Hell, Gedemer had to think in broader terms. “We met with the directors and they said, ‘We really want this movie to sound like it was back in that time.’ That seems to be obvious: ‘Hey, it’s set in 1890, we gotta make it sound like that.’ But it’s not always easy to get that authenticity,” he explains. “So, for example, we would take digitally recorded sounds but make them sound uglier. It’s a dichotomy — we use such sophisticated digital editing equipment to create the sound for a movie that was set in a time when the sound was crappy.”

Sound effects were run through some older tape machines, and in another instance, the crew jumped on the Web and purchased a Gramophone via eBay. “We recorded pieces of dialog from the movie onto the cylinder of the Gramophone and then re-recorded that back into Pro Tools,” he explains. “There are devices and software packages that will simulate this process, but we thought let’s just do it. That way we don’t have any question about whether it’s authentic or not. It will be authentic.” It wasn’t only bits of dialog that got that treatment, Gedemer says — 5.1 mixes of the static from the Gramophone’s cylinder made it into the track.

The Gramophone sounds were recorded at Abbey Road Studios in London, which is a far cry from the alleys of Burbank where Gedemer and his assistant spent six hours getting original sounds for an Eclipse gum commercial. “It really does make a huge difference to get that authentic sound,” he says. “We don’t necessarily try to digitally re-create it or fake it with all of our lovely tools. There’s the tendency to want to do that, since we have so many tools at our disposal. One of the most powerful tools in the creation of sound design is new recordings. Those new recordings are extremely important, not only to give new commercials or new pieces of work a unique sound, but also to provide me, as a sound designer, source material that no one else has. That makes me valuable in my future projects.”

One trend that both Gedemer and Morizet have seen over the years is the move toward blending sound design and music. “Some people, unless they’re hip to the business, don’t know the difference,” Gedemer says. “They hear a melody or rhythm, and that’s the line that gets drawn between music and sound design. Sometimes that line is blurred, particularly in commercials. It’s another layer that could be considered on top of the music. If I’m working with a composer and we’re trying to do something together, I have to be aware of the rhythm of what’s going on or my percussive elements will seem out of place or will make the music sound jilted.”

Morizet reports that she uses sounds liberally while composing music for commercials. “I use sounds and make them music,” she explains. “I’m incorporating them into more musical instruments. I like to play with that. It’s pretty different from the film world, which is not conventional, but more musical, because you don’t have to go that close frame by frame with the picture. The kind of work I do for commercials is more aesthetic-oriented.” She points to a Gatorade spot she composed last year where the cuts are extremely fast, which is quite different from her film credits. “I like to use a lot of textures and manipulate sounds, and it’s easier for commercials because you can put a lot of information in,” she says. “The music has to really pop out.”

The challenge of moving between films and commercials is interesting for Morizet. In the film world, she sees a number of challenges — working within dialog, reading cuts and pictures. For a commercial, the mood is different. “For a product, you have to understand the product, something a bit different. People want something very hype, but is the product very hype? The country is really huge and you have to please people in the middle and on the sides. So, how far can you go? [Agencies] want something out there and then people back up and they want something more traditional.”

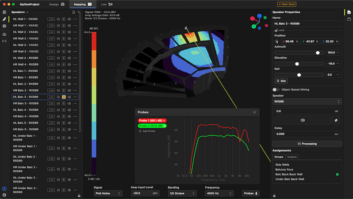

Not only is the musical approach different, Morizet varies her studio depending on the project. For films, she runs three computers, one with a video card, one with Pro Tools and one with Logic Audio. During commercial dates, she runs one computer with the video card, Logic and Pro Tools. “For a film, I can just go and see a scene I’ve done an hour before in the film and look at it,” she explains. “I find it easier. But if I do a commercial, I want the video card in the computer, because it’s faster and you move and the picture follows.”

It’s important, Gedemer adds, to keep your tools close: “I think that’s maybe more the key, because the psychological aspect, especially for a composer, of changing styles of music can be daunting. It’s a different set of tools to do a different style of music, but if you have those tools readily at hand and close to your chest, it’s easier. The same is true for sound design. If you have a lot of stuff that’s ready to go, it’s not so daunting of a task to make that gear change. You can cut down on your stress level a lot by having all that prepared ahead of time.”

Morizet, who’s moved from the score for the film American Friends and Lovers to an Eclipse gum commercial, agrees. “I’ve done so many [commercials] that it’s easier for me,” she concedes. “But the film work is a challenge because it’s like 40 minutes of music, it’s a lot of different characters and emotions. You have to be able to have a vision of the whole story and your whole score. If you have pieces that are very different in a score, they don’t look like a collage. It has to have some consistency in how you use the different themes. I love film because you are working for a story and you must be able to be noticeable and hide and bring some feelings. It’s quite difficult and complicated, but that’s the fun of it. If it’s too easy, it’s boring.”