The Electric Daisy Carnival is currently the largest EDM event in the world, drawing in over 345,000 people to the Las Vegas Speedway in 2013. Photo courtesy of 3G productions.

Described variously as “The New Rock and Roll,” “the rave wave” and “new rave,” EDM—electronic dance music—has become a major moneymaker in the United States in recent years. Having failed to ignite the U.S. public’s imagination previously in the 1990s when it arrived from Europe marketed as electronica, EDM has now gone well and truly mainstream, in the process spawning a year-round schedule of festivals that, in some instances, attract audience numbers rivaling the legendary rock gatherings of yore, such as Woodstock and England’s Isle of Wight.

The Electric Daisy Carnival is now reportedly the largest EDM event in the world. In June, it attracted an audience of 345,000 to Las Vegas Speedway, while 330,000 attended Miami’s Ultra Music Festival in March (although some argue those numbers are inflated as the official figures are based on combined daily attendance and many attended more than one day). The all-time largest EDM festival is reportedly Love Parade in Germany, first held in 1989, which reached its peak in 2010 with a crowd of 400,000, according to police estimates. Unfortunately, 21 people died due to crowd control inadequacies that year and the organizer cancelled any further festivals.

According to a report from the International Music Summit in Ibiza, Spain this year, electronic music is now worth an estimated $4.5 billion annually. Robert F.X. Sillerman, who founded SFX Entertainment in 2012 (having previously created the company that became Live Nation, which controls booking rights to over 100 venues worldwide), has committed $1 billion to acquiring EDM venues and promoters globally, and is about to go public. Recently, rival company Live Nation Entertainment partnered with Insomniac Events, the promoter behind Electric Daisy and other events, in a deal believed to be worth at least $50 million.

Suffice it to say, EDM festivals are big business. Despite that, EDM artists— typically, DJs—do not always receive the respect they deserve.

“One of the big challenges for rock companies doing EDM, initially, was taking them seriously,” says Dave Levine, better known as Dave Rat, founder of Rat Sound Systems in Southern California. Rat Sound handles production for the annual Coachella Festival, which includes a tented stage, Sahara, dedicated to EDM and this year added a sixth venue, Yuma, replicating a dance club in a tent. As many as 85,000 attend the three-day festival daily.

“DJs should not be underestimated,” Rat continues. “They are drawing as much, if not more, than a rock band. Just because there’s not a lot of inputs does not mean that it’s not crucial, and that any less attention should be paid. Everybody down the entire chain needs to understand that this isn’t ‘just a DJ,’ this is a performing artist who is equally as important as any rock band.”

“I think that DJs are the new rock stars, and I think that everyone in the production industry needs to treat them as such,” agrees Scott Ciungan, operations manager, Burst Sound & Lighting Systems, in Detroit, MI. Burst began during the rave scene about 12 years ago, he says, but has since expanded its inventory and is going after bigger markets. The company provided production for the Electric Forest festival in Michigan this year, which drew 40,000 attendees to the four-day, non-stop event.

“I’ve found that, not everybody, but a lot of these old rock and roll guys, look at these DJs as not a big deal. They are rock shows, and we need to treat them like that; I bring the same front of house gear to a rock show as I do to a DJ show,” says Ciungan.

The FOH gear may be the same, but there can be significant differences between a rock rig and an EDM system in the number of subwoofers. It’s not unusual for an EDM system to have a 1:1 or even 2:1 ratio of subs to mid/high boxes, in order to deliver the low frequencies generated by the artists and expected by the crowd.

Detroit-based Burst Sound & Lighting provided the sound reinforcement for the Electric Forest Festival in Rothbury, MI. Photo courtesy of Burst Sound & Lighting

“Obviously, for a rock show, you don’t need 46 subwoofers across the front of the stage; for a DJ show, you usually do,” says Ciungan, who adopted the one-to-one approach for Electric Forest. “Our strategy is, you can always turn it down. That being said, with DJs, I put the subs on an aux. With rock shows, I usually don’t do that because of today’s very finely tuned, full-range sound systems. We have high-pass filters these days, and you tune the system to be very smooth and coherent. But with DJs, because the music is a lot more dynamic, and you don’t really know what they’re going to throw at you, I think it’s safe to have that on a separate fader.”

Never mind the ratio, granularity is also important, according to George Stavro of Sonic Lab Audio and Integral Sound. Stavro specializes in club sound systems worldwide, along with business partners Steve Dash and Mike Bindra, and is the audio system designer for Electric Zoo, a three-day, five-stage EDM festival held annually on Randall’s Island, located in the East River between Northern Manhattan and Queens.

“The biggest thing I find lacking in most live PAs that reproduce club music is enough sub-low and enough mid-sub, and a differentiation of the two,” says Stavro, whose production sound vendor for the festival is Eighth Day Sound. “I find a lot of the arena-sized PA systems have plenty of subs for information down at 28 to 60 cycles. The thing is 65, 70 cycles to about 120 — that percussive, tight, boom that gets really muddy when you try and mix the two when you ask one box to do it. We like to have a combination of horn-loaded subs to move air and a lot of front radiating subs for that fast, transient bass.”

But overall, says Stavro, “I don’t think the flatness of sound is that paramount. With a lot of electronic music, it’s more an experience we’re trying to create. I’ve come up through engineering and designing club systems for the past 25 years and that’s what you’re trying to create—a tactile, physical sensation, without being overwhelmingly loud and fatiguing to the ears.”

Ciungan also favors a more granular approach: “What I’ve been starting to implement is a five-way system. We have a three-way top and then we have a dual 18-inch sub, and then we have a 21-inch sub. The 18-inch sub covers that first octave, maybe 80 Hz down to 50 or 60, and the 21 takes over at 50 to 20 Hz. We got Electric Forest down to 25 Hz, which was rather teeth-rattling.” Burst’s rig on the main stage included 24 Adamson E15 arrays with 24 T21 dual-21-inch subs ground-stacked in front of the deck.

But according to Julio Valdez, system tech for 3G Productions, which has facilities in Las Vegas and Los Angeles, EDM shows are no more bass-heavy than other events these days. That said, 3G assembled one of the largest collections ever of d&b audiotechnik products, including J-Subs and Infra subs, for this year’s Electric Daisy Carnival.

“In earlier times, it was definitely more noticeable that you’d have to double-up on subs than the conventional stuff. But with all the different genres of music, with the developing tastes and styles over the past 10 years or so, I’m seeing lots of bass being put up for all kinds of genres nowadays. Hip-hop, obviously, is another bass-heavy genre, but I’ve done some alternative rock shows with almost the quantities of subs required at EDM types of shows.”

In addition to its d&b systems, says Valdez, “We’ve recently purchased a Martin [Audio] rig, which has the MLX sub. That’s a double-18-inch sub and it’s really, really impressive. It can handle all of that energy down in the bottom very efficiently.”

EDM festivals, like rock festivals, often feature multiple stages, demanding precise pattern control in order to minimize spillage between adjacent performance areas. Line arrays and their associated DSP boxes are very good at providing tight horizontal and vertical dispersion in the high and mid ranges, while cardioid sub configurations can control the lows. But an EDM rig needs to not only control the dispersion, but also provide even coverage of the low frequencies.

Scott Cuingan of Burst Sound & Lighting Systems explained that subwoofers are vital at EDM festivals to deliver the low frequencies the crowds expect to hear. Photo courtesy of Burst Sound & Lighting

Attempting to replicate a dance club in an outdoor space is always going to be a challenge, not least because the stage where the artists and the main PA are located provide a focal point not typically found in clubs. As a result, production providers need to work a little harder to generate more even bass coverage, in particular, throughout the crowd.

“Cardioid sub arrays are a very big priority for me and, to go further, cardioid sub arc arrays are of very big importance to me,” says Valdez. “This music is highly focused on what’s happening in the bass frequencies, and I think that distributing that bass energy throughout the audience area requires sub arc configurations.”

A basic left/right system works fine for a lot of music, he continues, but for high-energy EDM, there can be as much cancellation as coupling with the subs. “All of those holes are a lot more noticeable when you have large, large systems running a lot of bass through them. I don’t, for obvious reasons, put cardioid sub stacks in delay positions—I don’t want any cancellation in the audience area. But I find that once the delay subs are time-aligned, they actually increase the bass behind them and couple well with the main stacks.”

He adds, “I align the [delay] tops to the main tops. I try to make it so the subs are not necessarily coupling with the tops, because that range is so variable, depending on where you’re standing. More importantly, I try to make it so the delay subs are coupling to the main subs and just try to find that happy medium. It’s not going to be perfect for everybody, but as close to perfect as possible.”

Rat has found delay issues to be somewhat more complex, at least in Coachella’s Sahara tent. “How do you sound reinforce a dance tent that has a primary focal point at one end, yet supplies subwoofer sound from all directions, and also deal with the timing issues? One concept is that you put the primary sound system over in the general vicinity of the performer—and then what do you do?

“You’ve got multiple sets of delay clusters; for us, it’s at least four or six clusters throughout the tent, some flown, some stacked. Do we set it so that when you’re at the back of the tent, the sound comes off the mains and then everything’s delayed so that it’s harmonized and passes through the tent and blows from one end to the other? Or do we have everything happening simultaneously at zero time, focusing all the sound energy to the center?”

The Sahara tent is so long—150 feet-plus—that generating a central focus creates a nasty slap-back. But, he says, “If you have the sound all blowing from one end to the other you’ve lost your dance club feel.”

The answer for that particular venue is a combined setup, says Rat, “Where we have the primary sound source with the bulk of the subs where the performer is, that can work with either a DJ or a rock band. The sound radiates from there and travels up to the first set of delay clusters, which are time-delayed, and as the sound passes, those light up. The sound travels from there and the rear delay clusters are at the same time as the mid-delay clusters, so the whole second half of the tent is one big dance tent at zero time.”

“We’ve got a dance tent in the back, and the whole dance tent is on a delay from the front. If we have a band like Nine Inch Nails or Kraftwerk in there, we have a rock focus. We give the sound engineers the option: They can switch the setting to a primary delay with all the focus put to the front or, if it’s a DJ, they can run it in the configuration we have.”

In the new Yuma tent at Coachella, which more precisely replicated a dance club, Rat encountered another challenge. After his crew had set up the clusters around the dance floor by eye, avoiding any obstructions, it became apparent that the system was not performing optimally.

“One of the unique factors is that the distance between all the clusters has to be precise,” he observes. “There was a big low-end hole right in front of the DJ. We hadn’t put a tape measure down, and those clusters were off by about a foot in each direction. Well, that cumulative issue means your perfect summation point is not in the center of the room. I reset the time delays to electronically compensate and set an equidistant point. Now that summation point was right where it needed to be; it was drawing people into the center of the room in front of the DJ, which hypes the DJ up,” says Rat.

“It’s something that I was aware of from setting up clubs over the years, and I hadn’t communicated how important these minute things are to the people setting up the rig. So that was a good learning experience for us.”

EDM systems also diverge from rock ‘n’ roll rigs where onstage monitoring is concerned. “About four or five years back, we started seeing line arrays being specified for monitoring, which we found absolutely ludicrous,” comments Stavro. “When you listen to a line array cabinet at two feet, you’re effectively listening to one box. If anything, you get more coupling on the low frequencies and the high frequencies will sound lacking to you, so you’ll try and accommodate that through the EQ on your channel and the whole PA will sound out of whack.”

Dutch DJ Tiësto was the first to demand L-Acoustic dV-Dosc foldback, recalls Stavro, and soon everyone was copying his tech rider. “I feel like they’ve jumped on the bandwagon. We provide it when it’s on a rider, but we’d rather use a direct radiating box, something like a [d &b] J-Sub and a C7 top—that sounds good. Or a really large, powerful stage monitor like the [d &b] M2, which is a double-12 and horn; something with quite wide dispersion designed to be listened to in the near field.”

Part of the problem is that DJs are unfamiliar with communicating what they need to the production provider, according to Valdez, who typically supplies d&b arrays such as the Q1, V8 or V12 for DJ monitoring. The artists end up working against themselves, requesting loud monitoring to overcome the PA, putting in earplugs to protect them from the monitors, then asking for louder monitors.

“The PA systems are so loud that getting the monitor system to penetrate through that requires tremendous amounts of SPL in their ears, right next to them. It becomes uncomfortable or hard to work with, so they put in earplugs to balance the loudness of the PA, and now the monitor rigs have to penetrate the earplugs!”

The situation may well be breeding a generation of deaf DJs, but high onstage SPLs do lead to better sound out front, Ciungan believes. “I’ve found that if you give the DJ a loud enough monitor system they will turn the DJ mixer down. If you don’t give them a loud enough monitor system and the monitor feed on their mixer is all the way up, the next place they go to for volume is the trims, or the channels on their DJ mixer and the faders—and that affects you up front. But they don’t really care, as long as they can hear.”

At Electric Forest, he says, “We put four Adamson SpekTrix—which is a small-format line array—boxes and four subs on either side of the DJ booth with really steep angles pointing up. That was really amazing.” The set-up was capable of generating 144 dB if the DJ chose to crank it up, he says: “Most chose not to! But if you give them that volume, they don’t push their DJ mixer as hard.”

The DJ mixer may in fact be the weakest link in the signal chain. “You’re relying on a $1,200, $1,500 pro-sumer product to drive a million-dollar PA,” notes Stavro. “Some of the Pioneer mixers, which are probably the most specified these days, are digital and have an algorithm in them that pretty much prevents clipping and digital distortion, but it adds to the signature and becomes quite band-limited. But you never rely on a DJ’s mixer to drive the PA; it’s always being sub-mixed or sub-routed some way or another.”

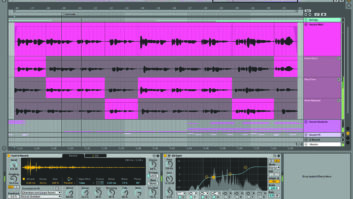

Ciungan agrees; he typically routes DJ mixers—indeed, anything from the stage—via a Midas XL48 preamp. “Everybody thinks, ‘it’s a DJ, it’s two channels, you turn it up, sit back and smoke pot at front of house for the rest of the show.’ That could not be more wrong! I find when doing DJ shows that I almost re-master every track they put through the system. You ride the graphic or your Lake Mesa EQs or your channel strips. You’re constantly making changes, because their music isn’t mastered well or they are poor-quality tracks, or some dynamic is weird with the music. It’s just so inconsistent from track to track.”

Ultimately, says Rat, EDM productions can be as diverse as any other music genre. “There is no definitive one way to do things. It’s no different than with a rock band: Determining whether you’re stepping on their artistic direction or fixing something that’s a flaw is definitely a judgment call. We make sure that we’re on a common goal with the artists, technicians and engineers. We try to the best of our ability to determine what they’re trying to seek, and utilize equipment, knowledge and resources to help them achieve that.”

This article originally appeared in Music Festival Business.