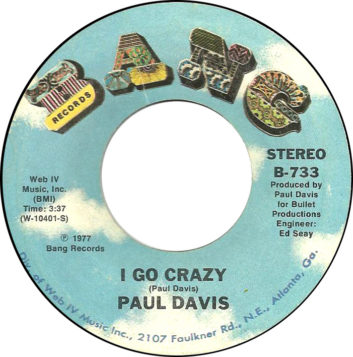

Paul Davis’ “I Go Crazy” was in the Guinness Book of World Records for the most consecutive weeks on the Billboard Hot 100 for four years in the late 1970s, until Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love” grabbed the mantle. While “I Go Crazy” peaked at #7 pop, it stayed on the charts for 40 weeks, from August 1977 until May 1978. More than 40 years later, the instant you hear the intro, the song is recognizable.

Originally, Davis wanted to give the song to Lou Rawls, who in 1976 had enjoyed a major crossover hit in the #2 pop/#1 R&B single “You’ll Never Find Another Love Like Mine.” Davis had made a few records, but had only scored one Top 40 hit with 1975’s “Ride ‘Em Cowboy.” Having not made quite the splash he had hoped, Davis was growing somewhat tired of trying to be a front man and thought maybe he’d just settle on being a songwriter instead.

One fine day in 1978, in the Atlanta area, Davis dropped by recording engineer Ed Seay’s apartment to play him a song he had just written: “I Go Crazy.” It was just Davis singing and playing piano.

Seay must have been impressed, as they then went to Web IV Recording Studios, where they both had been working, and began to demo it with the Korg Rhythm Ace, an early beat box. Davis went direct with the Fender Rhodes, and Seay went direct with the electric bass. They brought Alan Feingold in and doubled Davis’ part on the Baldwin nine-foot SD-10 Concert Grand piano (previously owned by Ferrante and Teicher for their live performances).

For a brief time, Web IV Recording Studios had been owned by Chips Moman when he had moved his operation from Memphis, where, from his fabled American Sound Studio, he produced Elvis’s classic 1969 comeback album, From Elvis in Memphis, as well as the King’s late-career classic singles, “In The Ghetto,” “Suspicious Minds” and “Kentucky Rain.” When Moman closed American Sound in 1972 and relocated to Georgia to start a new label, he left behind a trove of equipment, including instruments, an EMT 140 Plate and an Electrodyne console. The studio’s Ampex 16-track MM 1100 (with 1200 Transport electronics)\ was purchased by Bang Records and Web IV Music.

For the demo, Seay says he miked the piano with the same setup as when he started working at the studio: “I used an AKG 451 or 452 above, pointing at the second smallest sound hole, and a U87 over the low strings toward the back of the piano.”

Feingold also doubled the part on the ARP Odyssey. It was he who came up with the signature 10 notes that recur throughout the piece.

When they played the demo for record company head Ilene Berns, she told them there was no way they were going to give the song to Lou Rawls. “She said, ‘Go back there and make me a record,’” Seay recalls.

When they played the demo for record company head Ilene Berns, she told them there was no way they were going to give the song to Lou Rawls. “She said, ‘Go back there and make me a record,’” Seay recalls.

The Davis team went back in and added session musician Kenny Mims on guitar (miked with an SM57), and, as Seay explains, everything was recorded individually, which they called “layer cake,” mainly because they did not have a large session musician pool to draw from at the time.

They also wanted to add strings, so Seay went to New York (Davis declined to go, as he was not fond of flying) and met with Michael Zager, who would write and arrange a chart for three first violins, three second violins, four violas and two celli.

Zager said to Seay, “You’re going to take off those fake strings, right?” And Seay recalls saying, “No way, we love them.”

Seay explains that they loved the combination of the real strings and the fake strings, which were in place from when Davis played the Univox Stringman, heard in the moody sounds like French horns. Seay EQ’d the Stringman, while adding reverb and tape slap.

“Basically I EQ’d everything, to some extent,” Seay says. “Back then we only had a few audio crayons in the arsenal—EQ, compression, reverb and delay. Back in the mid-’70s I wasn’t compressing my mix bus either, but would get that added in mastering.”

The strings, along with the Stringman, are featured predominantly in the solo, but also in the choruses. They ended up editing the strings out of the intro altogether.

“We edited that out because it took away; it didn’t add to the arrangement,” Seay asserts. “The intro didn’t have the same emotional impact with the real strings on it. We brought them in down the line.”

However confident they were of having a hit single, neither Davis nor Seay could imagine a run of such magnitude as to warrant a Guinness Book of World Records citation.

When Seay returned from New York, Davis and he had one last piece of the puzzle to record: drums.

“Paul said, ‘I know this drummer from Jackson, Mississippi,’” Seay recalls. “Paul had lived there before he lived in Atlanta, so he and James Stroud were friends. So he flew James Stroud in. I had three tracks left on the tape machine, so I recorded kick, snare with some hat leaking in, and everything else, which were three toms with 421s and a couple of overheads, a couple of 87s, SM57 on the top snare, and I used an Electro-Voice RE20 on the kick.”

(James Stroud was then at the beginning of what has become a monumental career. He broke in playing on and producing sessions for Malaco Records, Jackson, Mississippi’s legendary blues/R&B label, before moving on to Nashville, where he rose to the top of Music Row’s producer hierarchy and has gone on to be one of the most successful Nashville label heads of the past half century. His resume includes 133 #1 records; 52 million-plus album sales; four Album of the Year awards; six Producer of the Year awards; and critical recognition as the driving force behind the careers of numerous mainstream country stars, including Clint Black, Chris Young, Tray Lawrence, Toby Keith and others. That’s just for starters. Davis was a Malaco songwriter when he and Stroud met there.)

Davis’ lead vocals were sung into a Neumann U87, as were harmonies and Seay’s background “oohs.” Seay mixed the song in about three hours, he says, with the reminder that there was no automation and he was marking the faders so that he could kill the hiss at the front.

“We went 30 ips and no noise reduction on the Ampex 16-track, and we went 2-Althougtrack, quarter-inch at 15 ips on the Ampex AG-440B to mix down to,” he explains. “And I think I had another tape machine running maybe some tape slap and mixed a little of that in.”

They had recorded one extra chorus, and having concerns with monotony over the course of the song, they decided to cut it, so out came the razor blade. Then Seay looked at Davis and said, “I don’t know, what do you think?” And Davis said, “Sounds done to me.” To which Seay said, “Yeah, me too.” And simple as that, the song was done and became the first single off Davis’s 1977 album, Singer of Songs: Teller of Tales. Glenn Meadows, head of Masterfonics, Nashville’s go-to mastering facility, put the finishing touches on the project. The album version of “I Go Crazy” runs 15 seconds longer than the single, as it retains Feingold’s wild outro.

They had recorded one extra chorus, and having concerns with monotony over the course of the song, they decided to cut it, so out came the razor blade. Then Seay looked at Davis and said, “I don’t know, what do you think?” And Davis said, “Sounds done to me.” To which Seay said, “Yeah, me too.” And simple as that, the song was done and became the first single off Davis’s 1977 album, Singer of Songs: Teller of Tales. Glenn Meadows, head of Masterfonics, Nashville’s go-to mastering facility, put the finishing touches on the project. The album version of “I Go Crazy” runs 15 seconds longer than the single, as it retains Feingold’s wild outro.

However confident they were of having a hit single, neither Davis nor Seay could imagine a run of such magnitude as to warrant a Guinness Book of World Records citation. “That was big at the time for an independent record company to have a fairly new artist to have something explode and hang on longer than any other record,” Seay says.

Although it was the right call for Davis to record the song himself, the artist’s initial instinct wasn’t exactly off the mark. In 1980 Lou Rawls did indeed cut “I Go Crazy.” Peaking at #37 R&B, it was his highest charting single of the ’80s.

Paul Davis died of a heart attack in Meridian, Mississippi, on April 22, 2008, a day after celebrating his 60th birthday.