Imagine how Narada Michael Walden must have felt while producing a project on Aretha Franklin—the Queen of Soul—and receiving a phone call from Arista Records A&R rep Gerry Griffith asking him to drop that record to work with an unknown 19-year-old singer he had discovered by the name of Whitney Houston for her self-titled debut album.

Well, Walden wasn’t about to ignore orders that came directly from record company head Clive Davis, and remembering the beautiful little 11-year-old girl who sat in the corner while her mother, Cissy Houston, sang background on Walden’s own 1976 solo album, Garden of Love Light, he dropped everything. Walden finished writing “How Will I Know,” produced the song and it became Houston’s third single from her debut album, and her second Number 1.

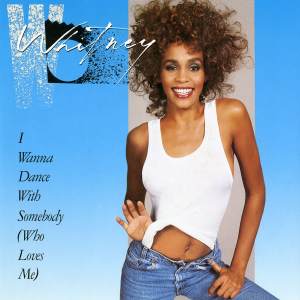

When it came time for Houston’s second album, Whitney, a year later, the artist was already a superstar. At the Grammy Awards the year before, she had won three statues, including Album of the Year, so this time Walden knew exactly what he was walking into and who he was going to be working with—and how. Walden ended up producing seven of her new tracks, including “I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me).”

Walden says he first heard the song when Clive Davis played him a demo. He could hear the hit in the hook, but says the demo sounded almost country. Definitely “white pop,” as he describes it. It became his job to make it “blacker, funkier and more raw,” he says.

The recipe for that, Walden asserts, was Randy Jackson’s Moog synthesizer combined with his own 808 Roland drum machine, which he and Preston Glass programmed. (Glass also programmed some other percussion, like that little castanet sound in the verses that Walden says he borrowed a la Phil Spector.)

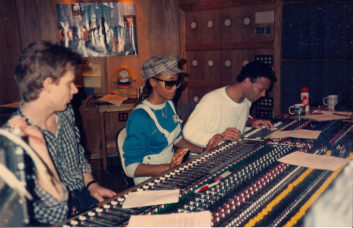

This track was recorded at Walden’s Northern California studio, Tarpan, with David Frazer, who was an in-house engineer at the time. (He still works independently for Walden.) The studio was equipped with a 48-input SSL G Series console and two Studer A80 tape machines.

Synths and Drum Machines

They began by getting a live track with Walden triggering the Roland 808 while Greg “Gigi” Gonaway played additional tracks from an early Simmons unit. Walden explains that it was the time of Prince and Michael Jackson, and real drums didn’t have the cutting-edge sound for that track to go “Wow!’”

Playing along with Walden and Gonaway were Walter Afanasieff on synths, Randy Jackson on bass synth and Corrado Rustici on guitar synth, with all going direct. Once they got the track, Frazer says they were 80 percent there.

“Once we’d cut it and edited it and put different takes together on multitrack, we’d edit them together with those four elements and come up with the track pretty much done,” he explains. “Each one would go in, and if they heard something they wanted to try to fix, they would go back and we’d individually do the bass or keyboards or guitars and so on. Our focus was really to get the band to move in time and feel together first, though.”

After the basic track was recorded, all the horns were overdubbed—Sterling on the synth horns and Marc Russo on real horns. “Real” cymbals, toms and hi-hat were also overdubbed, using a variety of microphones, including a Neumann KM-84 on the hi-hat; Sennheiser MD 421s on the rack toms; AKG C24s on drum stereo overheads, and two Neumann U-87s for the room.

Then they laid down a reference vocal so that by the time Houston came in, it already sounded like a hit. Frazer believes that the vocal was by Karen “Kitty Beethoven” Brewington.

“Houston’s vocals were cut with the AKG C24—one side only, we didn’t do it in stereo—into a Focusrite 110 module from a Focusrite desk, that stand alone for the preamp and EQ,” Frazer explains. “We did that primarily since we were recording on tape, knowing that we would have to lose a generation at some point and we were going to be bouncing it together and considering, of course, the effect of tape. We tried to compensate for that a little bit ahead of time so that we didn’t have to bring up the noise later on by adding top end. We tried to preload it a little bit in the upper mids and top end for tape. That’s what we used the Focusrite for. It had a really nice preamp in it. And we went from there into a Neve original metal knob—the 33609—compressor.”

Other outboard gear Frazer says he leaned heavily on for the song included the AMS devices—the RMX 16 (reverb) and DMX 15 (delay). “The two AMS units were really popular in the ‘80s,” he says with a slight chuckle. “But the reverb was the one that I thought really worked best with her voice. It was very bright and clear. We were really going for that very high-impact, very powerful upper-mid attack on it. That’s sort of where things were in the ‘80s; a lot of high-end impact. The AMS seemed to float it above the track; it didn’t get lost in the track at all. No matter what else was going on you always got this really pretty reverb her voice would ring out in no matter what. I really liked that. We also used the usual Lexicon PCM 41 and 42s for delays.”

Recording the Vocal, Back to Front

Walden developed an interesting way to capture lead vocals early on in his production career. He calls it a back-to-front technique to grab the gold. Houston would sing the song down from the top, maybe two or three times, and they would keep those. Then she would sing the song in segments, starting from the end with the out-chorus and ad libs.

“We had about 12 tracks for her,” Frazer explains. “We made a slave reel with eight to 10 tracks of music stems, generally speaking, and 12 tracks for Whitney to record to and one track to bounce to. We would record her, fill up those 12 tracks, starting at the end of the song to get all the fireworks done early, which was Narada’s technique. ‘You’re fresh, you’re energetic, you’re excited, let’s get all the out-chorus moments and ad libs done and blow it up. Then go to the second chorus and do the same thing, less licks and so on, then first chorus and then start doing the tedious stuff of the real minute details on the verses.’ We always kept those original rundowns because we always used something from them. You could have used any of the tracks as the song, she was just that good, and she would come up with parts during the song, too, like, ‘Let’s try this,’ or ‘Let’s try that.’

“One thing Whitney didn’t like was having to sing over and over again without any guidance,” Frazer adds. “If you could tell her what you wanted, she could sing all day. Just don’t say, ‘Sing it again.’’’

Walden says she was improvising on the outro and he wanted to make sure to capture that passion before recording the more “mundane” verses. He explains that he worked that way with Aretha Franklin, as well.

“Those artists come from the church,” Walden says. “You don’t want to wear them out like a racehorse, to run, run, run on verses and then you want fireworks and have nothing left that’s genius, fresh and pure. You always do the ending first. That’s what I learned. I get the ending fireworks first and everybody’s happy and the adrenalin is high, everything’s popping. Then go to the first verse and first chorus and second verse and second chorus and not worry about the ending.”

An “In Your Face” Mix

Frazer says the direction he got from Walden on the mix was that he wanted the sound of the entire track “in your face.” When asked to define what that means in terms of how he approached that as an engineer, Frazer says, “It means whatever you are focusing on must be brought up and given its moment. In that song, the vocal and the big horns are the two big things. Obviously, with Whitney there was not a big problem of her cutting through with her power and edge and abilities. So it was just a matter of giving everything as much of a moment as possible.

“The synths, of course, were all very powerful, so you had a lot of powerful elements fighting each other a little bit, but we found a way to give everyone their moment,” he recalls. “A lot of it had to do, honestly, with me using every module compressor engaged on the SSL and then not really heavily compressing the stereo, but individually things were compressed to pull them up forward as much as I could in their moment to try to give everyone their space. And the production really kind of allowed for everything to have its space; the track was pretty subdued in the verses and it’s all Whitney when the chorus hits; she and the horns are really slamming. Those two things needed to be the focus, and that was how I approached it and the way Narada wanted to hear it. There are a lot of SSL compressors. And I still use them today. They immediately give everything a little bit of an edge and a bite—amazing devices.”

Frazer says that Walden was amazing at producing Houston and knowing just how to get what was needed. Walden made notes while they recorded so they could put a comp track together and do a rough mix that night so in the morning Houston could hear a finished song. Walden says that was important to Houston, at least psychologically.

“We spent a lot of time on the comping,” Frazer says, “We had gone over the stems we created for the music already, as far as what he wanted to hear from everything; we had printed those and we were still working on the slave reel, so it really was, ‘Put those up and make it the way we like it, and work with Whitney in there with all the bits we just put it together.’ It was a very fast situation. The only problem I had, was keeping up with the two of them. [Laughs] There isn’t a machine that rewinds fast enough for Narada and Whitney. I would be pushing Rewind and they’d say, ‘Go.’ It would have been easier had it been digital.”

Frazer says that generally with Houston it was a high, happy energy and joyous in the studio. Walden and Houston would talk about the song and then just create. Frazer was not surprised the song was a hit. He usually knew by the time he heard the track with the reference vocal, and says of course by the time he heard it with Houston singing, he knew it was in the bag.

“I Wanna Dance With Somebody” became Houston’s fourth consecutive Number One, selling over a million copies and making it her first platinum single. The song was her biggest hit in the U.S. at that time and it won the Grammy Award for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance at the 1988 Grammy Awards.