Just as it appears, “We Are the World” was an immense and complex project, but for recording engineer Humberto Gatica, the meaningfulness and depth of his voluntary work has proven the most significant, precious and satisfying job in his storied career.

On the day we talked in early-March, Gatica was phoning from the studio that he leases at Lion Share Studios (a name that he now owns), where the very tracks for this historic musical event were recorded.

“The love and the passion still fill this room where I am,” Gatica says. “This was one song with one purpose—to save lives. The whole process from day one to completion, in terms of recording time until post-production and the record is out, selling, and money delivered, and people getting what they needed in the country of need, took us about four and a half weeks. It was a long process. Those on the production crew were working 14 to 18 hours a day.”

First there had to be a song. Gatica remembers that producer Quincy Jones spent about two and a half weeks just finding the right introduction, in search of what he felt would draw in the masses, because, as Gatica explains, “He needed it to be as strong as a hymn.”

All participated gratis in order to call attention to famine relief in Africa and provide food for the hungry. The process began sometime in the third week of January 1985 when three musicians arrived to cut in studio A of Lion Share Studios in Los Angeles: John J.R. Robinson on drums, Greg Phillinganes on keyboards and Louis Johnson on bass. The studio, then owned by Kenny Rogers, contained a Neve console and 32-track Mitsubishi digital machines, and “obviously we made slaves for several other sources of overdubs and for recording vocals.”

Setting the Foundation

Describing the piano miking in a visual manner, Gatica explains: “When you sit at the piano and you put the music in front of you, on the other side of that are two AKG 414 Es, and then where you lift the lid and put the stick up to hold the lid up, right in that area I put an AKG 452 on the right side and an AKG 452 on the left side. The close miking defines, and the other miking gives the air and the space.”

The bass went direct into the console processed through a GML equalizer and Teletronix LA2A, and the drums were miked with Shure SM57s on the tom toms, an AKG 452 on the hi-hat with 20dB pad (so, as Gatica puts it, the information wouldn’t become so aggressive to the mic and he would get a smooth sound). On the snare, he used three microphones: an SM57 and Neumann KM84 on top, placed in parallel angles and taped together so they wouldn’t move, and another SM57 on the bottom at an angle. Gatica used three vintage AKG C12s for the overheads—two for left and right, and one for the ride cymbal.

The track was recorded and then they added a reference vocal so that they could send it out to all the artists to hear. Gatica did the premix.

Previously, the core production team had gone to Lionel Richie’s home to map out with vocal arranger Tom Bailey who would sing what, and where. He says Bailey “did a brilliant job choosing the voice according to the melody of the song,” so he could figure out where he would place which artist strategically in the choir, first “based on their sound, their tone and the quality of their voice.” When they sent the demo to the artists, they sent each their specific parts, as well.

About a week after the tracking, the big event took place on January 28 immediately following the American Music Awards, since there would be access to lots of artists in town.

Leave Your Ego at the Door

And so began the ambitious undertaking at A&M Studios sometime after 8 p.m., with the recording of the choir—the three-part harmony singing the chorus “we are the world,” and ad libs with 21 artists that included the likes of Bob Geldof, Harry Belafonte, Waylon Jennings, Bette Midler and Jeffrey Osborne.

There were three M50 room mics, Schoeps microphones up-close for definition, and some Sennheisers for room depth. In the control room Gatica sat at a Trident console and made use of a custom mic pre made by a friend named Eduardo Fayed.

“I used about six or seven layers of microphones to obtain certain dimensions of the sound,” Gatica explains. “And that took a little bit because there were moments when people needed to pay attention to their intonation. Finally that got done.”

He says it took a little while—instead of an hour, it took an hour, forty-five—“A little longer because of so many parts. There were harmonies and counter melodies, sometimes a technical thing occurred. If a noise occurred, we’d have to stop and start again. There were so many people. Somebody might not be singing, somebody might be yelling, we’d have to stop. It was, ‘If you can’t hit those notes, stay the shit out of it! If you can’t do it, don’t even try, you’re going to mess up somebody else.’”

After the choir, there was a break, with some of the choir artists staying on to add lead vocals. Gatica placed six C12 vintage mics in a horseshoe configuration, counting on three people per mic. Each soloist had to lean forward, do his or her line and then get out of the way for the next one to sing their line. They would not have their own preferred mics. “That’s what we meant when we said leave your ego at the door and let us do our job,” Gatica says.

The whole group rehearsed the track six or seven times. “In other words, they had seven times to get their act together,” Gatica states. “Get your shit together on every pass because that’s the way it was; there was no room to retake and retake and retake. But that’s why you had the best artists.”

And that was that. Breakfast from Roscoe’s—“the best chicken and waffles,” according to Gatica—was delivered sometime around 8 in the morning, and artists left sometime around 9 a.m. Gatica left then, too, having been there since noon the day before.

In the two weeks that followed, several days of overdubs ensued with such players as David Paich, Steve Porcaro and Michael Boddicker on synthesizers, Michael Omartian and John Barnes on keyboards, and Paulinho Da Costa on percussion.

Then the mixing began, also at Lion Share on a Neve console. Certainly one of the main jobs was to select the vocal performances. “Remember we did six or seven passes,” Gatica says. “I have to select the best line and then I have to puzzle it all together between Lionel Richie to Paul Simon to Kenny Rogers—they all have to be threaded vocally and emotionally correct.”

Gatica put an edited mix together, and Quincy Jones approved and signed off. “People were singing in perfect tuning. There was no need for Pro Tooling and retuning, nothing,” Gatica claims. “The challenging part was when you put it together and create a sound that touches and justifies the purpose, and that requires an understanding of how to put it together. It’s like the brilliant director who shoots and shoots and shoots and shoots, and then you have the guy who cuts the right thing and decides what stays on the floor and what stays on the reel. Mixing requires that sensitivity. If the mix is not right, everything you have accomplished has been wasted,” Gatica says.

Despite its challenges, he couldn’t wait until the next day to get back to the studio to work on the project “to continue pursuing excellence, to continue polishing it,” Gatica explains. “Because of the nature of the recording and the circumstances, I remember before recording all the vocals, all the equipment was fairly new, like the mic pre’s, and I prayed that when I would arrive the next day to listen, there would be no buzzes or hums.”

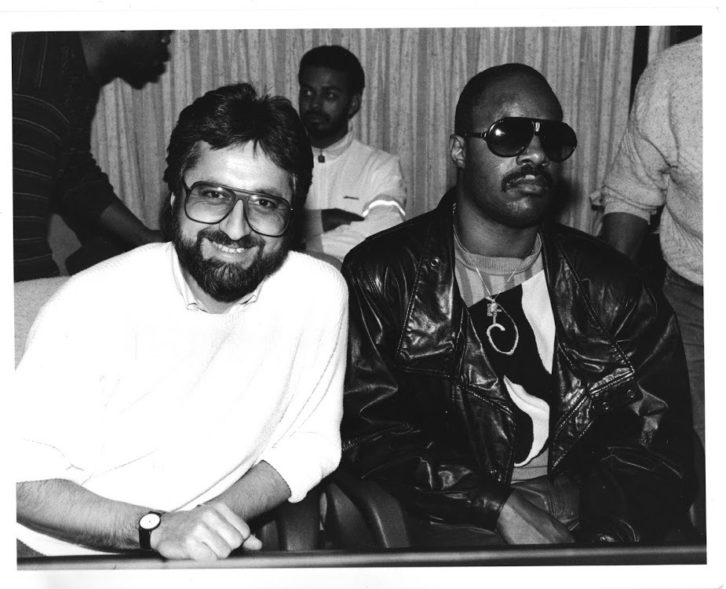

It was a couple of days before he called Quincy Jones, Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie to take the first listen. They gave some input, he did some touch-ups and the following day, Richie, Jones, Stevie Wonder and Kenny Rogers came to listen at 11 a.m. to what was considered the final mix.

“Everyone started crying because here was a record that had never been done before, with an incredible amount of talent, from stars to superstars to legends. I saw Stevie next to me and he was crying and he said, ‘It’s beyond my wildest imagination,’” Gatica says, adding that he spent another day on touch-ups.

That he was honored to be a part of the project that earned three Grammy Awards and raised more than $63 million for aid to Africa and the U.S. is an understatement for Gatica.

“First, to be asked, then the purpose of the project and the love and the passion of everyone who became a part of it,” he says. “Then watching later when Ken Kragen and the group of people were in Africa delivering something amazing. If you are saving one life, I would say our job was done, but there were many, many, many lives saved. This was the most significant part of my career.”