Leo Sayer’s “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” began with a jam at Studio 55, which, pretty much, had everybody in the room dancing.

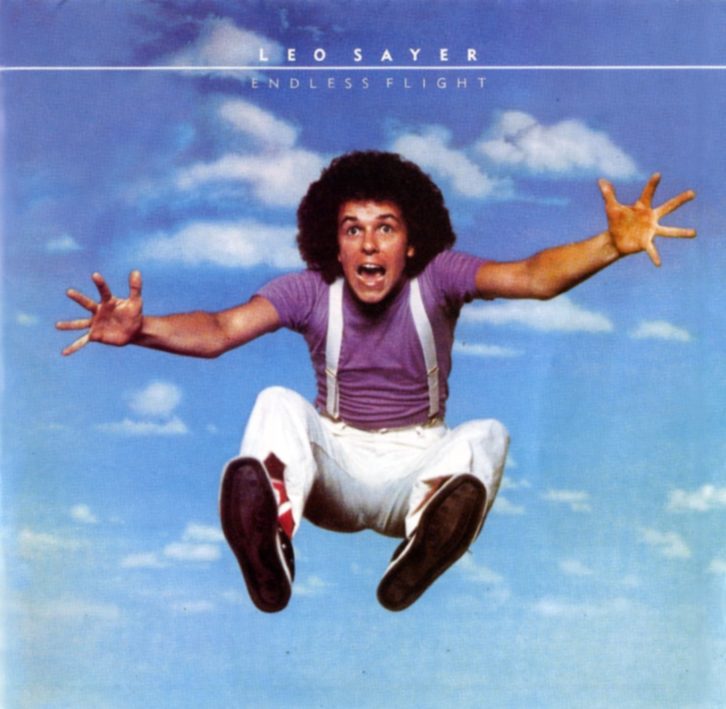

The genesis of the song arose out of a challenge Sayer and drummer Jeff Porcaro had driving into the L.A. studio each day. The two had hit it off from the moment they met on Sayer’s 1976 record project, Endless Flight, produced by Richard Perry and containing the hit single that’s the subject of this month’s Classic Tracks.

Sayer had been reticent about recording with Perry, as the famed producer hadn’t been very interested in Sayer’s compositions up until that point. But Perry had put a band together of some of the best L.A. session musicians, and Sayer was sold on the team when he walked into the studio on the first day. “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing,” Sayer says, came out of thin air.

“There were no mobile phones in those days, so Jeff and I couldn’t call each other [from the car],” Sayer told me via Skype from his home in Australia. “We would set a challenge, ‘Tell me what song you dig on the radio on the way in [to the studio].’ This one morning I came in and said, ‘Oh, man, I just heard this song from Shirley & Company.’” Then Sayer sang a few lines from “Shame Shame Shame.”

“Jeff said, ‘I heard that as well. What a groove! It goes like this.’ And he started drumming, and I started singing and pretty soon the whole studio was into it.”

Sayer says that everybody—Porcaro, Ray Parker, Jr., Lee Ritenour, John Barnes and Willie Weeks—was jamming, and he started coming up with words spontaneously.

“Richard throws the reel, which was nearly finished, off the tape machine,” Sayer recalls. “He puts on a new reel and he’s shouting and barking at the guys, ‘Record now!’ And that’s how the jam got onto tape.”

They returned back to the business of the album, but about a month later, Sayer recalls, Perry called him up to his office.

“He said, ‘You need to listen to this, Lee…,’” Sayer says. “On came the jam session, and I had to admit, though rough, and even with the track stopping and starting, it had the makings of something great—something really fresh and groovy. As I reacted favorably, Richard just sat back in his chair with that big trademark Cheshire cat grin on his face, saying, ‘Now that is your hit.’”

“…It had the makings of something great—something really fresh and groovy. As I reacted favorably, Richard [Perry, producer] just sat back in his chair with that big trademark Cheshire cat grin on his face, saying, ‘Now that is your hit.’” —Leo Sayer

Perry immediately sent Sayer into Studio 2 with songwriter Vini Poncia to finish the song and find the hook. There was a tape deck and baby grand piano, and the two hammered out some ideas.

“Vini mentioned that on the jam tape he heard me telling Ray [Parker, Jr.] that ‘he made me feel like dancing,’” Sayer recalls. “I didn’t remember that specifically, but hey, maybe that was it. I started to formulate the words into a pattern that might fit, to which Vini said, ‘Let’s shift the key.’ So we did, and there it was, simple but sweet. Vini stopped, saying, ‘No more, I gotta get to the chiropractor.’ We both laughed ‘cause we knew we had it, and it had taken all of five minutes! Vini left, and I took the tape we made up to Richard, where the grin just got a whole lot wider.”

Bill Schnee for Three Hours

Sayer thought the song had been forgotten until one day engineer Bill Schnee—who was in the middle of working on Steely Dan’s Aja with producer Gary Katz at Producers Workshop Studio—gave Perry a call.

Producers Workshop was Schnee’s favorite place to record because it had a custom console that “sounded amazing,” the engineer says. “All of my favorite consoles, including the one I built for my studio, were custom-made. It was very simple, with old-school technology in it, but very simple electronically, so it sounded incredible. They had a Stephens tape machine which, in my opinion and many others’, was the best-sounding multitrack ever built. There was nothing in it compared to every other tape machine. It almost amounted to a custom tape machine. John Stephens didn’t make a whole lot of those. That was really the heart and soul of why I loved the sound of that place.

“Gary told me when we started that there would be a revolving door of drummers,” Schnee continues. “Sure enough, Steve Gadd comes in for two days. I was familiar with Steve, and I knew Richard would be. When Steve came in we did the first track and I was just blown away with him. I think it was between the two Steely songs we did that day, but I called Richard and I said, ‘You know this Steve Gadd?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ And I said, ‘I’m recording him right now.’ And Richard said, in typical fashion, ‘Do you think I could do a session with him?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, but you’d have to come over here to Producers because I’m not going to have to get the drum sound again. I’m very happy with the drum sound.’ I was going to record the song ‘Aja’ the next day.”

Katz gave his approval to lend out Gadd with a three-hour cap.

Schnee remembers that Perry brought over the recording of the finished song. He also brought over Ray Parker, Jr. (guitar) to join in with Katz’s crew of Larry Carlton (guitar), Chuck Rainey (bass) and Gadd.

“Gadd did what Gadd does, and did an amazing job with his drag snare, which worked perfectly on the song, and it was wonderful,” Schnee states, adding that the recording was made simple—most likely there was a kick mic, snare mic, three tom mics, two overheads and a hi-hat mic. Schnee says he probably put LA2As on the guitars and an 1176 on Rainey’s bass. The session was cut live with Sayer singing a rough vocal.

Schnee says they got the basics down in two hours, and then Perry asked to do another track. Schnee told him he could do something else if he could get it done in an hour’s time because the rest of the guys would be back then. They managed to cut the basics to the album’s third single, “How Much Love,” in an hour, which was unheard of for Perry.

Schnee returned to his Steely Dan duties at Producers Workshop, and Perry went back to Studio 55 to complete Endless Flight.

Sayer says he learned the art of comping from Perry on Endless Flight. It was take after take, which he believes was meant sometimes to improve the performance and sometimes just to give Perry endless options. And then a group of them would go over each word in an arduous process to choose which take to use.

“This group would most often be me, Richard, Howard (Steele, engineer) and Gabe (Veltri, assistant engineer)—but sometimes his secretary Robin Rinehart, or Kathy Carey, and maybe studio manager Larry Emerine would get called in there, too,” Sayer recalls.

“One night I remember producer Peter Asher was visiting and was called into the group,” Sayer continues. “And I loved him for suddenly standing up and stating, ‘Richard, you’re so f–ing pedantic!’ to which Richard replied, ‘Surely that’s a good thing, no?’’ So we’d sit there trying to stay awake while Richard would ask, ‘I like the way he sings the ‘when’ from take two, but then listen to what he does with it in take 19. Better, no?’ We’d demur to him, of course, and he’d go on to say, ‘Okay, next word.’”

Although Sayer couldn’t recall specific technical elements about “Dancing,” he did remember the overall experience about the making of the album:

“On one reel of 2-inch-wide, 2500-foot-long, 24-track multitrack tape, recording at 30 ips, we could get about 16 minutes of recording time, maybe enough to record three songs, or three takes of one song, so you can see that we went through an enormous amount of tapes. Copying this tape onto a sister machine, this running at a different speed of 15 ips, gave us twice the recording time.

“Therefore, we could fit about six or seven takes of a song on it, one after the other. I remember us recording up to 15 takes of some songs, something almost unheard of in other studios. These days, songs are nearly always recorded to a click track, and that makes overdubbing more parts onto it easier. But in those days that hadn’t yet been invented.”

Sayer mentioned in particular that drummer Jeff Porcaro, who, while he didn’t end up on “Dancing,” was on other cuts, including Sayer’s next hit off the album, “When I Need You,” was a human metronome. He says that when Perry cut from one take to another, the time was impeccable.

Explaining the cutting process back then, Sayer describes: “To slice tape, you take a fine razor blade, cut diagonally and use special sticky tape to bind together the joins—this is the easy bit. Lining up those cuts, that’s where the fun comes in. You take a white wax pencil, shut the motors down, put the machine into free roll so that you now have manual control. Then you roll the spool across the open heads with the speakers turned up so you can listen to the throaty signal of the slowed down drum beat you’ve chosen to hack into as you manually roll it past the heads. Expertly choosing your cut points, you mark the tape with the wax marker, then graft the two different takes together with the sticky tape, resting the tape carefully onto a metal guide, re-spool it on to the reel and play it back. Imagine how long this could take to get Richard happy with each song, and you have the story of the making of Endless Flight.”

Schnee says “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” sounded like a smash to him right away. Between Sayer’s falsetto and the melody, he says, the song captivated him immediately.

“The opening line pulled you right in, and it had a great hook.”

And he was right about its success. The song was Sayer’s first Number 1, hitting the top spot on the Billboard charts in January 1977. Sayer and Vini Poncia went on to win a Grammy Award in 1978 for Best R&B Song.