When it comes to laying the cards on the table, few can do it like Merle Haggard and George Jones. They built their careers on straight-shooting lyrics and uncensored opinions, particularly about Nashville, as well as the music industry in general.

Twenty-five years ago, Haggard and Jones entered the studio to make their classic album A Taste of Yesterday’s Wine. Legends already, they continued their successful solo careers, enjoying hit records, sold-out tours — and a few speed bumps along the way. Last fall, the two reunited for Kickin’ Out the Footlights…Again, a concept album of sorts in that it presents the two performing each other’s songs, in addition to four duets of old and new material. Music Row has changed dramatically since their last joint effort, but Haggard and Jones remain the same: two unmistakable voices that don’t hold back when creating real country music or talking about it.

So why wait a quarter-century to get back together? “I honestly wish we hadn’t waited so long because it was a lot of fun being in the studio doing both albums,” says Jones. “I think Merle feels the same way I do — we don’t like the fact that mainstream radio doesn’t play us but a lot of ‘Americana’ stations do, and we still have our crowds on the road. Traditional country fans know what real country is supposed to be, and regardless of whether or not radio wants to play us, we have people wanting to see us that much more because they don’t hear us on the radio.”

Haggard adds, “I want to increase the airplay and George does too. But we’ve got to be thankful for the airplay we have received over the years, and even now there’s a light at the end of the tunnel: A radio station in L.A. went totally ‘classic country.’ It’s happening in the U.S., and I’ve got to say that if it happens that whoever pushes the button on the other stations doesn’t want me, so be it. There’s XM and Sirius, and all the new conditions they’ll have to deal with. People are tired of force-feeding. I think the public will somehow rise up and take over.”

When it came to recording their second album, selecting tracks from each other’s remarkable catalogs was no easy task, but the outcome is a unique spin on familiar material, as well as a chance for the original artists to listen to their own classics with a new perspective. “The songs are refreshing when you hear somebody else sing them,” says Jones. “When I heard Merle do ‘She Thinks I Still Care’ and ‘The Race Is On,’ it brought a new feeling to the songs. I started listening to what the songs are really saying, instead of the routine of being on the road and doing them night after night. I got a different feeling, but a good feeling.”

“I know at least 40 of his songs, and he could do the same with me,” adds Haggard. “My best performance is ‘Things Have Gone to Pieces,’ and ‘Window Up Above’ is pretty nice. His best are ‘Sing Me Back Home’ and ‘The Way I Am.’ ‘All My Friends Are Strangers’ is wonderful. It’s an interesting album to listen to. I enjoyed it myself, and I don’t listen to my own music. I wasn’t there when George cut my songs [Haggard cut all his tracks in one day], but he was there when I sang his, and he was highly happy. He worked a tour, came back, did his tracks and I heard the finished product. He blew me away.”

Putting the project together and taking it from studio to CD required not only a master producer and engineer, but also individuals with an understanding of and genuine love for the heart and soul of this sort of traditional country music. Jones called upon Keith Stegall, award-winning producer and songwriter, renowned for producing every Alan Jackson album (except Like Red on a Rose), and his longtime engineer, John Kelton. The team had worked with Jones on his Cold Hard Truth and Hits I Missed…And One I Didn’t albums, but it was their first time with Haggard.

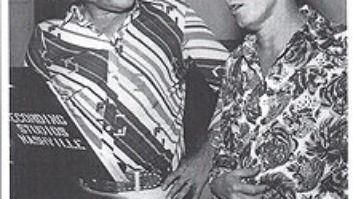

“I recorded all the tracks over a couple or three days and sent them to Merle,” says Stegall. “Then he came to town and we cut a couple more tracks with two mics set up like they did it years ago. They were standing side by side, and it was incredible to look through the glass and see them. The studio environment was like a couple of old fishing buddies relaxing. They both have high levels of intensity, but like different colors of intensity — one might be blue and one might be green.

“Sometimes as a producer, you forget what you’re doing and get lost in the mechanics, then you pinch yourself and go, ‘Oh my God!’ In the back of my mind, growing up with traditional country, I thought it would be a high point in my career to someday record these icons; it so happened that it came together with this album. It was tough to try to be ‘normal’ around them because I’m in such awe of these guys. It was the first time I had ever really been around Merle, and to sit behind the console and suddenly hear that timeless voice coming through the speakers, and look and there’s the voice attached to the man.”

Stegall has a simple rule he applies in such situations: “When you deal with artists of that caliber, the best thing you can do is stay out of the way but [still] be involved. All I wanted was to be able to capture it. I tried to let the process be as natural and unencumbered as it could be.

“The great artists I work with have such a strong sense of what they sound like and the record they want to make,” he continues. “I put together the corresponding players and re-create that. Merle and George can do whatever they want, but there’s an identifiable sound to both of them and my job is to stay close to that and gently nudge them if necessary — in my passive-aggressive way! I’m not a fan of punching lines in because people fall out of character. I would rather keep the imperfections so it feels like a performance.”

From Haggard’s perspective, “Keith is young, energetic, has good ideas, good instrumentation and good ears,” he says. “I don’t know anyone who could have done it any better. He let me do whatever I did. I didn’t know his ears, I had no opinion of him [going into the sessions] because I didn’t know him, and it was important to me to have someone in the control room I know and who listens to me. I don’t need someone from Nashville — I don’t much trust anybody there — but I see what Keith did and I have faith in him. We now have a track record and we believe in each other.”

The clinical sterility of contemporary country hasn’t bypassed Haggard’s discerning ears. “It comes from too much scrutiny; it’s a production mistake,” he says. “Reality doesn’t allow for that much perfection. The warts and moles they shave off are the things people identify with and call your style. You could hear Elvis breathe on a record. Now they take it out as unnatural noise, extract the humanity and it sounds like an electronic, perfected piece of shit. I’d much rather hear an artist who can actually sing in front of a room with a guitar. Some of these artists go on the road and use tuners on the mic so they can’t go out of pitch. That has nothing to do with talent, that has to do with bullshit.”

To preserve those “warts and moles,” Stegall relied on Kelton, his senior engineer and “right hand.” The two met in 1987 when Kelton was engineering at Nashville’s Studio 19. “John majored in cello in college and he has a sense of purity as to how things are miked and go to tape,” says Stegall. “He’s very organic, with a mind from another planet as far as how to mix, so you feel like you’re listening to a band in your living room and it’s not squished or EQ’d.

“Before we track, he gives me all the options, and on something like this I wanted analog,” Stegall continues. “So I bought the rest of the analog tape that was left in Nashville — I got all I could and stuck it in a room in my studio! Then they transferred it from analog to Pro Tools so we could work a little easier. The album was done at Starstruck, Reba McEntire’s complex. We brought everything to my SSL room where the rest of it was assembled, then we went back to Starstruck for a couple of piano overdubs. I have an SSL G Series and Pro Tools HD and analog — a little old and new. John and I are partners and he put together what we needed in our chain. I put in big monster monitors, APCs, because I like the big sound when I listen back.”

“The board was an SSL 9000 J and Starstruck has a good bit of outboard equipment that we used, too,” Kelton says. “For tape we used a Studer 827 16-track for the drums and bass and a Studer 827 24-track for everybody else. That was fed into a Pro Tools HD system. I mixed on an SSL 4056 G+ at Keith’s studio and mixed to the new 900 [tape] that used to be the Emtec; this is the first thing we’ve done on it. We used the Ampex ATR-100 half-inch. For mics, Merle was an old Neumann 47 into a Martech preamp and LA-2 compressor that was hardly used at all. George was an older-stock U87 into a Martech into a Teletronix LA1 compressor that we’ve used with him for a while. There was no EQ on either one of them.”

The setup, says Kelton, was specific for Haggard and Jones. “The way we ran the tape was a little different from what I’d normally do. The 16-track was actually being sub-mixed to three tracks on the 24-track, so should anything need to be punched in, we wouldn’t have to wait for anything to lock in. I’ve done this in the past, when you want more than 24 or 16 tracks of analog and you don’t necessarily want to wait for the machines to lock up when you’re doing quick punch-ins.”

Like Stegall, Kelton was excited about the project and was willing to stand back and let the magic happen naturally. “I just stay out of the way,” he comments. “That’s the smartest thing I can do. I set them up in the room with the players and no baffling between them. The drums were in a smaller booth and the room was open for their singing. Everyone was pretty close together, all playing together. This was the first record I’ve done that way. Usually, singers cut with some kind of isolation around them.

“This experience was one of those things where if they can pull it off and it works, it’s great,” Kelton continues. “If things bleed or need to be fixed, it can become a nightmare. The beauty of Merle and George is they’re always ‘on’ and there was no trouble at all. I can’t think of anything that got punched in. If there was any bleeding, it just became part of the sound.”

Recording technology continues to expand at a steady clip, but for pros like Haggard and Jones, it’s the same picture in a new frame. “It’s like all golf courses are different but the same,” says Haggard. “You start at the first hole and end up at the 18th. There are different ways to make records, but it’s still all about what goes in the mic and what it sounds like coming out the other end. The way they do it now and the way we did it years ago is different to the people who make the records, but it’s the same to the artist. You go in and do it and hope they don’t alter it from reality too much. I’d rather have those warts and moles.”