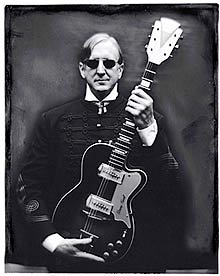

In the Two-Plus Years since our last “Mix Interview” with T Bone Burnett (July 2006), the producer/musician has been working nearly nonstop — as usual — and churning out some of the best music of his career. Julie Taymor’s film Across the Universe, for which he served as an arranger and co-producer of the music, brought the music of The Beatles to a new generation in a fresh and exciting way. The marvelous Robert Plant/Alison Krauss album Raising Sand, which he produced and played on, was a surprise smash hit (Mix, December 2007) that also spawned one of the coolest tours — complete with Burnett on guitar — of 2008 (August 2008).

He produced what is unquestionably B.B. King’s best album in decades — One Kind Favor — and John Mellencamp’s deep, soulful and revelatory Life Death Love and Freedom. The latter is the first album featuring a new sound innovation developed by Burnett, his trusty chief engineer Mike Piersante and others called CODE, which purports to deliver true high-definition audio to DVD, MP3 and other delivery formats. It’s all still slightly mysterious, involving certain proprietary pieces of gear and techniques, but hey, if it sounds good, we’re all for it!

Burnett was selected to be this year’s recipient of the TEC Hall of Fame Award before CODE was made public — purely on the basis of an amazing career that stretches back to Bob Dylan’s ramshackle Rolling Thunder Revue. Highlights include a handful of intelligent and provocative records with the Alpha Band and solo; an array of brilliant albums he’s produced for the likes of Los Lobos, Elvis Costello, The Wallflowers, Roy Orbison, Counting Crows, Gillian Welch, Cassandra Wilson and, yes, even Spinal Tap; and creative soundtrack work for films ranging from the Grammy-winning O Brother, Where Art Thou? to Cold Mountain to The Ladykillers.

We caught up with Burnett at his ElectroMagnetic Studio in L.A. in early September as he was finishing up work on a new album by longtime pal Elvis Costello. Our conversation this time centered around his recent projects.

So what’s the story with this new Elvis record?

It’s a really cool group of songs, a couple we’ve written — we’ve been writing things for movies here and there, so there are a couple of those — a few songs he wrote for this opera on Hans Christian Anderson.

Did Hans Christian Anderson have an opera-worthy life?

I think so! [Laughs] You know, Elvis does so many things at once it’s hard for me to keep track. But there are a few songs that are from a sort of more serious place, and then there are a lot of songs he’s had around that he hadn’t put anywhere, and things we felt like doing in the studio. But it’s essentially a string band record, and then I’m playing really loud electric guitar. [Laughs] But he’s singing really loud rock ‘n’ roll music.

It’s got some great people on it: Mike Compton, Jerry Douglas, Stuart Duncan, Dennis Crouch, Jim Lauderdale, Emmylou [Harris]. There’s no drums at all.

That’s a twist from your recent productions, most of which seem to have a couple of drummers going most of the time and percussionists.

Right, as many drums as possible! [Laughs] Well, there are no traps on the Elvis record, let’s put it that way. Mandolin is a great drum.

On the B.B. King album, I noticed how you use maracas or shakers, and thought, “Who uses maracas these days?” I associate it with folks like Bo Diddley or Johnny Otis. It adds a lot.

I agree. You know, I don’t like hi-hats. I don’t like things that proscribe time very strictly. The way I hear hi-hats is, it’s the drummer saying, ‘Here’s where the beat is’ — ti-ti-ti-ti — and everyone sort of follows that and it can make the beat stiff; accurate perhaps, but stiff. So we don’t use hi-hats, and all the things that would play those notes — the quarter-notes or eighth-notes — are these big shakers; not just one or a pair of maracas, but like 10 or 15 different gourds with beads in them or nuts, and they go shh-flooosshh! [Laughs] So it expands and broadens the beat.

Last time we spoke, your solo album True False Identity had just come out and you were about to tour. How was your experience of the tour and putting out the record in this business climate?

The tour was the best and most expensive vacation I’ve ever been on. [Laughs] I loved doing the shows, and it was as good a band as I could dream of.

By “expensive vacation,” do you mean you had to pay for the tour because Columbia doesn’t do that anymore?

[Laughs] That’s right!

Things have changed, as your buddy Bob Dylan once sang.

I’ll say. I could probably buy Columbia now. [Laughs] And if we go much longer, they might just give it to me. Be sure to mention that was a joke!

T Bone/BMG. That has a nice ring to it.

[Laughs] The music business gets stranger and stranger. But touring again was fun. I’ve been working with Sam Shepard in the theater for about 10 years now, and I’ve gotten more comfortable in the live environment — and the live experience has become more important to me.

As a kid, I fell in love with sound and I sequestered myself in the studio for most of 40 years and created my own universe and my own world, and came out [to play live] hesitantly because you can make a mistake in the studio and nobody knows it and things are private and calm and much more controllable. Going out live is a whole other animal and experience.

I don’t think of you as a perfectionist, though.

I’m not at all. That’s not it. It’s just a different way of doing things. Painters paint in private; they don’t usually get a big crowd around to watch them. I grew up with a lot of painters and I probably had more the mind-set of a painter. I always thought of making records as the equivalent of what my friends who painted did.

The Plant and Krauss album, Raising Sand, was one of the real delights of last year. Why do you think it connected so well with people?

My point of view on it was this: Robert wanted to do it as a band. He didn’t want to do it as a “duet record” — he sings a verse, she sings a verse, they sing the chorus together, they look at each other dreamily. [Laughs] He wanted to create a band, which I thought was a thrilling idea. These two singers are so extraordinary, I knew having two singers in a band together would be extraordinarily powerful.

It’s a testament to the fans they have, too, that they were given the leeway to do this project that was outside of either’s style.

Right. They were allowed to follow their muse. Of course, there were Led Zeppelin T-shirts at the show and there were Alison Krauss fans, and the first night, in Louisville, I think there were eight fights that broke out in the crowd! [Laughs] But very quickly it became clear that most of the people who came were also Raising Sand fans, so people were very respectful.

I would think that the music must have matured out on the road. After all, the album really chronicles the beginning of that band being together. Will there be some document of the tour?

We’re going to do something, for sure. We have a few more dates in September/October and I hope to record two or three of those. What I’d like to do most of all is record another record next year and then do a residency somewhere — like maybe do a week at The Fillmore in San Francisco — and shoot a DVD of the residency. We’ll definitely continue on in some way. It’s too much fun to abandon.

When I was thinking recently about how you came up with the obscure songs for that and the B.B. King album, I wondered to myself, “What would T Bone have done with Elvis Presley?”

Oh, God, would I love to have made a record with Elvis! I would have gone right to Maybelle Smith; go right back into the deepest part of New Orleans.

It’s interesting you should say that, because when I listened to the B.B. King album I was surprised right off the bat that the first track, Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “One Kind Favor,” is more New Orleans than Texas, where Jefferson was from, or Mississippi, where B.B. is from. It’s got Dr. John so prominently on piano.

It does have a lot of New Orleans in it. The whole record has a lot of swamp in it. But it’s really the whole [Mississippi] Delta, not just New Olreans. And when you think about it, B.B. always used those New Orleans mambo beats and got into different time signatures and different feels. He was always adventurous that way.

It’s amazing how much presence there is to both his singing and his playing. He’s got the growl but can also still smooth his voice to a near-croon, and his guitar playing is rougher than we usually hear.

We roughed his guitar a little bit. We ran about three or four different amps into different rooms to try to get the right sound for each song. Because he’s sort of been using this one sound he got dialed into a long time ago, and we let him use that because he was comfortable with it, but we also used some old [Fender] Tweed Deluxes, maybe a Vibroverb and a Vibrolux — great, old, grungy tube amplifiers. And his voice is more powerful than it’s ever been. B.B. is rightly regarded as one of the best guitarists ever, but I also believe he’s a better singer than he is a guitarist, so I really wanted to focus on his singing. His voice has mellowed into this almost Bill Eckstine vibrato, which is deep and rich and powerful.

How did working with Mellencamp come about?

He called up, and said, “T Bone, I want to make a record in five days, just acoustic guitar. I just wrote these songs in the last week. Do you want to come up here and record them?” I did, so I went up to his place and we started — he would put down a tune with acoustic guitar, and his guitar player, Andy York, was there and he’d play something. Then his bass player would come down from Cincinnati and play bass. Then, about the third or fourth day, the drummer showed up. I have a lot of guitar on there. It just kept growing. It was a moveable feast.

When you’re producing someone like Mellencamp, what does that really entail?

With all these artists I’ve been working with lately, the main thing it entails is listening really hard. To be awake and listen hard and to be active imaginatively, to realize what he’s talking about in the song — is the story getting told, the message getting out? How can that best be supported? I work more on that level now than on the level of telling people what notes to play.

Is it fair to say that almost everything we hear on albums you produce these days, regardless of what technology was used to record it, is sonically something that could have been done in 1958?

Well, it could have been put on tape in 1958, but it couldn’t have been put on album in 1958 because there’s a density to sound now — we’re putting more bottom on now than the machines could have taken. Digital technology does not really operate in the sonic world very efficiently. You’ve seen a small JPEG picture file blown up and how quickly it comes apart and pixilates? Well, the same thing happens with digital music. If you take an MP3 that might sound pretty good on ear buds and put it through a serious sound system, you start hearing these digital noises, static and chatter. People can’t hear them on ear buds, but they’re still being affected by them and their ears are still being shocked by those sounds. So we started experimenting with ways to get digital to sound better.

And that led you to CODE? I never would have expected for you to become an audio guru!

[Laughs] I always have cared about sound. I think we’ve gotten to a place where we’ve come to a comprehensive and complex system — really, it’s more of a method than a system — where we can make digital sound on any format sound tremendously better.

I’ve read the articles and I still don’t understand what the base of it is.

One of the seriously adverse effects of the decline of the record business has been a decline in quality control of the manufacturing, production and distribution of recorded music. I’m a child of Bill Putnam — I knew him a little, but mostly learned his methods through Allen Sides, who taught me so much about audio — and I’ve taken his theories and methods and applied them to the current environment we’re in. Really, this is something we’ve developed for ourselves. I don’t have great hopes of moving this whole industry that’s bent on self-destruction.

Well, also, it doesn’t sound like there’s a box other people can buy.

Part of the reason I have to be somewhat circumspect in talking about it is we are filing for a few patents. There won’t be a box you can buy, but we are automating the process.

Which, generally speaking, involves what?

It’s a quality-control system — like THX is a quality-control system — and when we put our brand on it, the listener will know it’s been made to the highest standards. It’s a quality-control system for which we have developed a new set of standards that all relate back to the RIAA standard. You see, when the RIAA and NAB standards came in around 1950, there was a period of about 30 years where everyone was speaking the same language [sonically]. But with the advent of digital sound, those standards have been thrown out the window. Now people are listening on such a wide variety of devices and environments and formats. We spent several years experimenting and looking at the optimal ways to produce every one of these kinds of files. We’re now trying to produce MP3s to the same standards as Bill Putnam recorded to.

We’re taking MP3 seriously because people listen to them. So why should they listen to MP3s ripped by god-knows-who that was ripped from a CD that was made from a pressing plant that ran it on a CD-ROM setting?

So we can hear that swampy, distorted guitar just as T Bone intended!

[Laughs] There may be people who think these records we make sound muddy because they don’t sound like bright pop records, but they’re actually super-hi-fi. We’re optimizing for every one of these formats and devices. For someone who’s been doing this for 40 years and spent so much time trying to get the sound right, the way we want it, to have it then leave our hands and have maybe 10 people with no connection to the work making important decisions about how it sounds is unacceptable. The time is right for the artist to take control of the whole process, from production to manufacturing to delivery.

Blair Jackson is the senior editor of Mix.