When saxophone great Michael Brecker died of leukemia at the age of 57 this past January, the music world lost one of its most versatile, prolific and influential players. The sheer scope of his career is staggering: He played on some 900 albums in nearly every musical style imaginable, from rock to funk to folk to Latin to jazz, with such “names” as John Lennon, Elton John, Frank Sinatra, Steely Dan, Joni Mitchell, Lou Reed, Pat Metheny, Funkadelic, Paul Simon, James Taylor, Chick Corea, Frank Zappa, McCoy Tyner, James Brown, Dave Brubeck and hundreds more. The tenor sax giant played in a number of jazz and fusion groups, from Dreams to the Brecker Bros. (both with his trumpet-playing bro Randy) to Steps Ahead, toured with many more and somehow also found time to put out a dozen or so albums under his own name. He won 13 Grammys, the most recent for his 2003 CD, Wide Angles. He was loved, admired and respected by nearly everyone who ever had any contact with him. No question about it — this is a huge loss, deeply felt.

But Brecker left us with one helluva “good-bye” album: Pilgrimage, recorded in August 2006 and mixed just days after his death, features Brecker playing in a fantastic all-star jazz quintet featuring guitarist Metheny, bassist John Patitucci, drummer Jack DeJohnette and (depending on the track) pianists Herbie Hancock and Brad Mehldau. Not surprisingly, Brecker had long histories with all of these jazz titans, who bring imagination, exquisite taste and, when needed, real firepower to nine Brecker compositions that span a wide range of jazz moods, from quietly contemplative numbers to intricate and unpredictable mid-tempo pieces that feel like well-constructed puzzles, to blistering bop-inspired workouts. Far from seeming like the sad coda to a brilliant career, Pilgrimage feels like the statement of an artist at the peak of his powers. That Brecker could summon the strength to make an album this brilliant when he knew he was dying makes this an extraordinary story, but Pilgrimage would still be a masterwork even if he was still with us, back in New York and L.A. studios, pushing toward his 1,000th album appearance.

At Legacy, L-R: Pat Metheny, Jack DeJohnette, John Patitucci, arranger/producer Gil Goldstein, Michael Brecker, Herbie Hancock

Photo: Darryl Pitt

It seems somehow appropriate that Pilgrimage was recorded and mixed by another jazz legend, Joe Ferla, whose own career spans nearly four decades in New York studios, working with a who’s who of the jazz world (including all the players on the record, multiple times) and a number of pop artists (such as John Mayer, for whom he engineered much of the Grammy-winning Continuum).

“It was an amazing record to work on,” Ferla says of Pilgrimage. “Obviously, they’re all brilliant musicians and it was really an honor to be part of it. We’re so lucky we even got to make the record, let alone have it come out so well. Michael had been sick for a couple of years. He was really weak and a lot of the time he was in the hospital. But there was a little window of opportunity, and I got a call from his manager a couple of weeks before we went into the studio — it was really short notice, and I was thankful that my schedule was open. Michael was feeling good, and so he and the group had a couple of rehearsals and then we got together at Legacy Studios — the old Right Track — and if you hadn’t known that he was sick, you wouldn’t have known it from those sessions because he did eight- to 10-hour days. He played so incredibly well — what’s on the album is what he played — that we never went back and fixed anything. He got sick after that. We did have two days scheduled to let him go in and take another crack at solos if he wanted to, to see if he could top what he did live, but that never happened and he didn’t need to come back in.

“This was really difficult, complicated music; it kicked everybody’s asses,” he continues. “Not one musician had an easy time with it. But everybody played brilliantly and rose to the occasion — for Michael, but also for each other because that’s what a great group does. Michael was pretty tired at the end of each day, no doubt, but everything was always very upbeat.”

Did Ferla suspect at the time he would never work with Brecker again? “I suppose in the back of my mind I thought there was a chance this could be Michael’s last recording,” he answers. “But he showed up in such good spirits and he looked so good, you’d think, ‘This guy’s not dying.’ I think we all felt that way, and it’s nothing that we ever talked about.” Producers listed on the project include Brecker, Gil Goldstein (who produced Wide Angles), Metheny and the longtime bass player in the Pat Metheny Group, Steve Rodby, whom Ferla describes as “a real Pro Tools wiz.”

The live tracking took place over three days in the big room, with Ferla recording direct to Pro Tools. “You can put a 90-piece orchestra in there,” Ferla says, “so we weren’t using that much of it. I had Michael in an isolation booth so we’d have the option to fix any mistakes he might have made — but he didn’t! I also had Jack [DeJohnette] in a booth and Pat in a booth. But the piano and the bass were in the large room, with the bass baffled off.”

As for mic choices, “On Michael I used a Neumann U67 and a Coles 4038; a blend of those. The 67 gets you that three-dimensional tube sound with the nice, beautiful air, and the Coles gives it more body; it’s a warm-sounding mic. I had both mics right next to each other, as close as I could get them.” Additionally, on a couple of tracks Brecker played an EWI [Electronic Wind Instrument], “which sounds a little synthetic to me at times,” Ferla notes, “but we EQ’d it and [later] re-amped it to get a little analog warmth out of it to make it not quite so thin and bright.

“In the piano, I put a couple of Beyer MC 704s, and a [Neumann] U47 tube and a KM84. Brad [Mehldau] picked a 9-foot Steinway and Herbie [Hancock] had a Fazioli. Pat has a DI and a microphone inside his guitar, and then we re-amped him in the mix with a Beyer M88. On drums, I used KM54s for cymbals, Beyer M88s on tom-toms and bass drum, and a KM184 on the snare.” Ferla eschewed room mics because they made the piano and bass “too washy. If I’d had the drums in the room,” he says, “I would’ve put a room mic up or if Michael had been in there with them.” Preamps were Neve 1081s.

Shortly after the tracking sessions were completed, Brecker fell ill again, underwent more chemotherapy and, just a few months later, passed away. In the meantime, Rodby edited the tracks in Pro Tools to everyone’s satisfaction and then, as Ferla relates, “About a week-and-a-half after Michael died, we were in the Euphonix [System 5] room mixing the record. I have to say that was probably the most emotionally draining mix session I’ve ever done. Everyone tried to check their emotions at the door, but I couldn’t really do that myself because I’m not that kind of engineer; I need to get emotionally involved in the music.

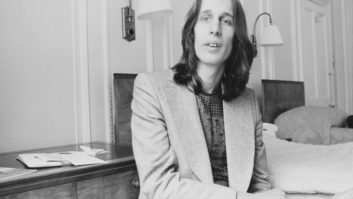

Brecker and co. discuss tracks that engineer Joe Ferla calls “difficult, complicated music. Not one musician had an easy time with it, but everybody played brilliantly.”

Photo: Darryl Pitt

“The fact that he had just died made it very difficult to me. I probably knew Michael 25 or 30 years — a long time. And here was this brilliant music, and it sounded like he was in the room with us. Susan, his wife, came by every day. His kids came by probably every other day: Sam is 12 or 13, and his daughter, Jessica, is 17 or 18. And that added to the emotion of what was going on, too. But we’re all really proud of it. We gave an extra 100 percent trying to second-guess what Michael would have liked if he’d been around for the mix. I guess I was playing a little mind game that Michael was there, that he heard what we were doing and liked it, tricking myself psychologically to not get too depressed about what really took place.”

The mix itself was relatively straightforward, requiring little processing beyond some Lexicon 960 and 480 reverb for each player. “I don’t have more than one player in a particular reverb,” Ferla says. “Each was carefully fine-tuned to the particular instrument. I think those Lexicons are the smoothest and most natural-sounding of all the digital reverbs.”

Months after the mix sessions, Ferla is still devastated by Brecker’s death: “It’s such a huge loss. Michael was one of the sweetest, most humble, gentlest men you would ever meet. He would play something incredible, then look at you and sort of shrug his shoulders, and say, ‘Was that okay?’ And your jaw is still dropped and you think, ‘Okay? Are you f***ing kidding me?’” he says with a laugh, then turns serious again. “So talented, so talented. I’m just happy to have been able to work on this project. To be in this company was definitely a highlight of my career; a real privilege.”

LISTEN: Must Play

Misbehavin’