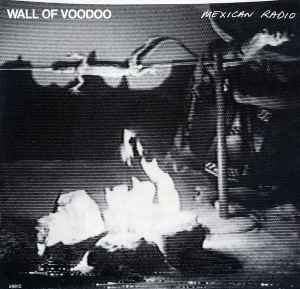

You have to love a band that comes up with an image like this one: “I wish I was in Tijuana/Eating barbecued iguana.” That was just one of the many odd delights found on the Los Angeles band Wall of Voodoo’s quirky, infectious hit from the winter of 1982 to ’83, “Mexican Radio.” Actually, calling it a “hit” is slightly misleading — it only made it to Number 58 on the Billboard singles chart. But that was an astonishing feat for such an idiosyncratic outfit, and the fact is, if you listened to hip FM radio at the time — any station that played punk or new wave — the song was inescapable. In those nascent days of MTV, too, the bizarre, arty video for “Mexican Radio” was in heavy rotation for weeks. It’s no surprise, then, that the song has also appeared on some two-dozen compilation albums through the years. Admit it — you’ve only been reading for one paragraph and the chorus of “Mexican Radio” is already stuck in your head!

You have to love a band that comes up with an image like this one: “I wish I was in Tijuana/Eating barbecued iguana.” That was just one of the many odd delights found on the Los Angeles band Wall of Voodoo’s quirky, infectious hit from the winter of 1982 to ’83, “Mexican Radio.” Actually, calling it a “hit” is slightly misleading — it only made it to Number 58 on the Billboard singles chart. But that was an astonishing feat for such an idiosyncratic outfit, and the fact is, if you listened to hip FM radio at the time — any station that played punk or new wave — the song was inescapable. In those nascent days of MTV, too, the bizarre, arty video for “Mexican Radio” was in heavy rotation for weeks. It’s no surprise, then, that the song has also appeared on some two-dozen compilation albums through the years. Admit it — you’ve only been reading for one paragraph and the chorus of “Mexican Radio” is already stuck in your head!

The group’s founder and leader, Stan Ridgway, “had bounced around quite a bit as a musician before Wall of Voodoo,” he says. “When I got out of high school, I wanted to join Miles Davis’ band and replace [guitarist] John McLaughlin. Obviously, that didn’t happen. But I did some jazz things and I also played in a Top 40 band. Then, I ended up in an office across from this rehearsal hall, which became The Masque [the seminal L.A. punk club] trying to do soundtracks. I met [WOV guitarist] Marc Moreland at The Masque — he was playing in a band called The Skulls, and Chas [Gray, WOV keyboardist/bassist] was also in that band. They were a three-chord punk band, but what Marc was playing really intrigued me; I couldn’t quite figure it out. We found that we had a lot of things in common: We both really enjoyed Brain Eno, and Kraftwerk was a big band for us at the time. So it was fairly natural for us to get together and play music.

“We were very fired up about the idea of doing something different,” Ridgway continues. “Back then, our whole idea was to make music that no one’s ever heard before. The cliché licks of the time would come up and we would excise them, until finally there wasn’t anything left where you could hear obvious influences. We were pretty tenacious about getting rid of figures that sounded like anything else.”

Initially, Ridgway and Moreland operated as Acme Soundtracks, turning out moody instrumental music using an assortment of synthesizers, guitars and rhythm machines. “I was the recordist,” Ridgway says. “I started out recording as a kid with this great 2-track Sony TC630. It had a ping-pong dial where you’d take what is on track 1 and mix it onto track 2 while you recorded on track 2. Then you’d take track 2 and move it over to 1. So in overdubbing, you’d get this natural compression from the tracks building up. All of the early Wall of Voodoo demos were done on that TC630.”

Wall of Voodoo was formed by the duo in 1977 with the addition of guitarist Moreland’s brother Bruce, who played synthesizers. Live, Ridgway played Farfisa organ with a crude rhythm machine on top. The name of the group derived, in part, from Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound — not bad for a band that was trying to play, as Ridgway termed it, “Top 40 avant-garde.” Two years later, the band added Gray and drummer/percussionist Joe Nanini. Ridgway has said that he became the lead singer by default, but the unusual and often surreal lyric imagery was his, so it made sense for him to be the front man. Actually, Ridgway didn’t sing so much as intone over the burbling synths and at times unusual rhythms.

WOV recorded the demos for its eponymous debut EP on the TC630, “and then we went into the Wilder Brothers studio on Santa Monica Boulevard in Westwood and spent a lot of time trying to re-create what was on the demos,” Ridgway says. “It was very frustrating.” The combination of the EP and a live performance opening for The Cramps at The Whisky in L.A. was all it took to convince IRS Records chief Miles Copeland to sign the band. IRS helped distribute the EP and then paid for the recording of the group’s first full-length album, Dark Continent, in 1981 at A&M Studios. (IRS was an A&M Records imprint.) While not earning the group much airplay, the album was critically well-received and, coupled with their dynamic live shows, increased the group’s profile as they approached their second album, Call of the West, which would contain “Mexican Radio.” In the meantime, Bruce Moreland departed the band, leaving the group a quartet.

For Call of the West, Copeland enlisted the services of a British musician and fledgling producer named Richard Mazda to helm the WOV sessions. Copeland had liked what Mazda did producing The Fleshtones in New York, so he brought him out to L.A. to meet with Wall of Voodoo. “That meeting actually became a recording session,” Mazda says. “That’s when I did ‘Mexican Radio,’ which I did back-to-back with ‘Suburban Lawns.’ My memory is that it was like a 48-hour session; I imagine I went back to the Tropicana [hotel] at some point during that period, but I don’t recall.”

In the memory of both Ridgway and engineer Jess Sutcliffe — who was also brought over from England and had worked with Mazda on projects by The Fall, Birthday Party and a couple of other groups — the recording team actually first heard the group in a pre-production rehearsal, but then immediately went into the studio to cut “Mexican Radio.” “It was a weekend session,” Ridgway relates. “So much of the construction of the song took place in the studio.”

The germ of the song came from Marc Moreland, Ridgway says. “Marc and I used to go to rehearsal in my ’67 Mustang and we were really fed up with Los Angeles radio. We were very cynical and we thought it was much better to tune into these Mexican radio stations that would waft in across the border — of course, now the stations are all over Los Angeles. Anyway, when we’d come across one of these stations playing mariachi music, we’d get all excited — ‘Great, man, I’m on a Mexican radio!’ I didn’t think a thing about it until one day, Marc came in with this little one-minute [demo tape] sketch of that great guitar lick and him singing, ‘I’m on a Mexican radio,’ kind of mumbling it. I thought, ‘Wow, that is just inspired and twisted,’ and immediately some of the other lyrics came to mind and where to take it, although it was still a puzzle.”

The session for “Mexican Radio” (and all of Call of the West) took place at Hit City West in L.A., “a funky studio I think the band had selected mainly for budget reasons,” engineer Sutcliffe offers. “They had a Soundcraft console and one 24-track [recorder]. They had a lot of quirky little rooms — like they had a live chamber-ish room where we used to stick the drums.”

“The main studio room was quite large, about 45-by-20,” adds Mazda, “but we also did things like stick Marc’s guitar amp in the restroom at the back of the studio. We really made our own world in that studio. Marc brought in 200 plastic dinosaurs and we completely customized the studio to the point where anyone else coming in would have thought, ‘These people have lost their minds!’”

“It had everything we needed and it was small enough and comfy enough that it wasn’t intimidating,” Ridgway adds. The mic selection was fairly basic: mostly Shure condensers and various AKG models, like the 414.

The instrumental track for “Mexican Radio” was built up from a foundation of two different rhythm machines: a Roland 808 and a Kalamazoo Rhythm Ace, a primitive box that had once been owned by Daws Butler, the voice of Yogi Bear and Huckleberry Hound. “There’s some of it on ‘Mexican Radio,’” Ridgway says. “I believe it’s in the ‘Western Mode.’ We recorded it through an amp.”

In fact, nearly all the synths and keyboards on “Mexican Radio” were recorded through amps — from Fender Twin Reverbs to AC-30s — rather than direct. “We had the Minimoog set up in the studio room, as was the Oberheim-8 voice sequencer,” Mazda says. “They would’ve been going through amplifiers in the studio room so Joe [Nanini] could play along. A certain amount of it was pumped into his cans, but it was also recorded in a semi-live fashion. A lot of the synths on Call of the West I would have taken a live feed and a direct feed, and tried to mix them together. I was also a big Brian Eno fan: He used to take feeds off Phil Manzanera and Brian Ferry [of Roxy Music] and shove it through his EMS suitcase synth to screw with the song. So that was a general approach I took with synthesizers — I very seldom recorded them direct. I always did something to the sound.”

As for the ultraspeedy Oberheim sequencer part that opens “Mexican Radio,” Mazda says, “I didn’t have to do much to that because the voltage-controlled amplifiers on the Oberheim were very unreliable — they hadn’t sorted out some of the voltage problems. But it was just the effect we were looking for.”

Ridgway freely credits Mazda with being the principal architect of the song’s production. It was Mazda who battled with drummer Nanini to get the simple, metronomic snare beat onto the chorus: “The Roland 808 had been set at something ridiculous like 240 bpm. I wanted something slower to denote that it was the chorus.” And it was he who fought for the differing “radio” treatments of the lead vocal throughout the song. “At first, they thought it was a really lame idea,” Mazda says, laughing, “but I was utterly convinced of its rightness.” The effect was simply achieved: “You can get the radio voice by using subtractive EQ, but I probably also put it through a UREI 1176 and squashed it a bit. I also did a lot of radio-type things on guitars and voices on the whole record.” Sutcliffe also reveals, “Stan would also occasionally sing through these little megaphones he’d fashion instead of using EQ.”

Another source of sonic strangeness that Mazda came up with was to put sustained guitar notes through a Radio Shack Archer Mini-Amplifier. “It’s an idea I nicked from Peter Gabriel,” he says with a laugh. “Hugh Padgham told me about this micro-amp that has a 1½-inch speaker, a volume control and an input, and it does really interesting things to guitars. I would often mix it in when I’d double-track guitars.”

However, it was Ridgway’s idea to have some snippets of actual Mexican radio wafting in and out of the song. “I used to love making these little 15- and 30-second tape loops on these cassettes you could get at Radio Shack,” he says. “I probably thought I was being like Brian Eno or something. When I used to go down to Mexico a lot, I’d sometimes go to this bar in San Felipe where you could bet on the dog races in Mexico City. You’d sit there drinking, and then you’d find out later if you’d won. So I recorded [the radio call] of the dog races and some of that made it on there. We flew it in.”

Sutcliffe remembers an even more complex methodology for getting the “radio” onto the track: “We took a piece off the radio and made it into this huge ½-inch tape loop that had to be about 18 feet long. I remember there were four of us with pencils and this great loop going around and around, hoping to God it would go around for one more minute!”

In the end, all the experimentation and sweat paid off. The group had a cranking good start to what would be the group’s finest album, and as they learned quickly after release, their one and only hit record. “‘Mexican Radio’ is the first time I heard something the band did and I said, ‘This is a hit,’” Ridgway says today. Mazda, too, “had that weird feeling you only get now and then — ‘This could definitely be a hit record.’ I knew that when it came on in a pub, if people were drunk enough, they’d sing along with ‘I wish I was in Tijuana eating barbecued Iguana,’ and the ‘radio, radio’ chorus. It had a striking sound and a great story. Nobody else has ever made a song that sounds quite like that.”

That was Wall of Voodoo’s peak. Ridgway would leave the band after a couple more albums to forge a fine solo career that is still going strong. He put out two albums last year: Blood is an instrumental work based on photos by Mark Ryden and Snakebite: Blacktop Ballads & Fugitive Songs is a more traditional (but hardly “normal”) song-oriented album. It includes a song called “Talkin’ Wall of Voodoo Blues Pt. 1” that explicates some of the WOV saga. Marc Moreland died of liver failure a few years ago. Nanini died of a cerebral hemorrhage. Mazda has had a varied career in and outside of music — he’s currently working on what will doubtless be a very colorful memoir. Sutcliffe is a Grammy-nominated engineer who has worked with a wide assortment of acts, including Prince, Toto and the Rolling Stones.

We’ll give the last word to Ridgway: “The ‘one-hit wonder’ status of ‘Mexican Radio’ is not something to be ashamed of. Obviously, it’s not all the band was about, and it’s possible the light from it blinded some people from hearing other things the band did, but it exposed a lot of people to our music who probably wouldn’t have heard it — and maybe because of it, after Wall of Voodoo I was lucky enough to continue to write songs and make music. If there wasn’t a ‘Mexican Radio,’ you probably wouldn’t be talking to me now.”