Though very few will admit it, each and every one of us, all day and every day, attach labels to the people, places and things that make up our own private world. Ninety-nine percent of the time, this process is unconscious and autonomic, like breathing or the movement of muscles, and it’s harmless. Labels simply provide a means by which we navigate the world—a tiger might be labeled a threat, same as a smell might be deemed alluring or the sound of fingernails drawn slowly across a chalkboard painful. These types of labels, unconsciously tucked away in the brain, are good. They are part of a vast biofeedback system based on objective recognition and causal response. They’re necessary—and they carry no judgment.

In our private lives, most of the labels we attach to people, places, things, and even ideas are relatively harmless. A neighbor might be labeled “conservative” or “liberal,” same as a pending piece of tax legislation in the U.S. Senate. An older aunt who only visits at Thanksgiving, smelling like mothballs and alcohol and giggling at odd times, might become known forever more as “eccentric,” while the newborn who never makes a noise is considered a “good baby.” The 60-year-old woman who lives alone down the street, with an overgrown, weed-riddled yard of aging shade trees that keep the entire property in the dark, might live the rest of her life not knowing that three generations of neighbors had dubbed her the “cat lady.” Still, it’s relatively benign in the grand scheme of things.

It’s when we venture further out into the public arena that the act of assigning labels starts to have the potential to do harm. A shy 12-year-old boy who does well in science is considered a “nerd,” a young woman with severe dyslexia is teased, perhaps called “dumb,” because she has a hard time reading in front of the class, or a freshman on the basketball team is labeled a troublemaker for all four years by faculty and coaches alike, without consideration that he has been shuffled between 10 to 12 foster homes in his brief 15 years on the planet, or that he’s an incredible painter and getting an A in art.

This is when labels start to come with judgment, and not just when they involve people. A neighborhood downtown that is labeled “urban,” means something very different to a potential homebuyer than a bordering neighborhood that realtors have decided to refer to as “gentrified,” or “up and coming.” A “loft” evokes a different image than a “condo.” And a “Clean Forest Initiative,” pretty as it sounds, might actually involve loggers and the clear-cutting of old-growth trees. If you don’t take the time to look beneath the surface and find out more about the whole person or the whole story, labels have the power to both harm and deceive.

Look at what happened in our own industry. With one throwaway comment from a London stage about then-President George W. Bush, lasting no more than 5 seconds, the Dixie Chicks were branded as traitors, communists, and a whole lot worse. In one night, their career, which had been riding a peak, was over. In the documentary Miss Americana, Taylor Swift talks openly about the agonizing struggles she went through in trying to shed the “good girl” label that had been drilled so deep into her psyche by the country music industry that at first she didn’t know how to speak out for what she believed in and simply be herself.

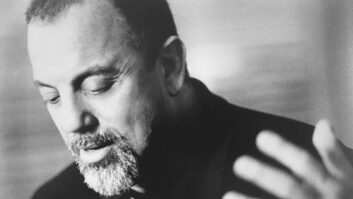

All that being said, I can’t imagine how this month’s cover star, two-time Grammy-winning Producer of the Year Jack Antonoff, deals with the bloggers, critics, anti-fans and strangers who toss labels at him like candy, in social media and in old-school publications—everything from “fraud” to “genius,” from “Savior of Pop” to “Destroyer of Pop,” from “producer on a meteoric rise” to “hitmaker who has lost his touch.” None of it bothers him, Antonoff says. Sometimes he just laughs. Sometimes he counters by shocking them with a tune. He’s been thinking about music nonstop for most of his life, before even picking up a guitar at age 12 and writing his first song.

I don’t pretend to know Jack Antonoff. I did my research, watched some interviews and clips, listened to his music, and then we talked for an hour by phone. He doesn’t seem like he’s bent on destruction, and there’s nothing mediocre about him. He seems to know who he is at this point in life, and he’s comfortable in his own skin. There was no rock-star ego. He looks and acts like someone you would want to hang out with.

Near the end of our conversation, I brought up a New York Times op-ed piece written by Jeff Tweedy a month earlier, titled “I Thought I Hated Pop Music; ‘Dancing Queen’ Changed My Mind.” In it, Tweedy talks about growing up punk in Chicago, where teens would often find identity through hating something else, typically a music genre. Foreigner fans had big combs in their pockets, and ABBA fans were simply idiots. By the end of the essay, Tweedy is in deep lament for the 35 years he lost when he could have been playing ‘Dancing Queen’ at least once a day.

Antonoff’s response? “‘Dancing Queen’ is such a great f—ing song!”

—Tom Kenny, Co-Editor