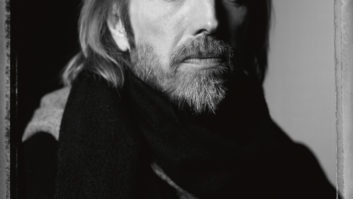

“I’m thinking it may be the last trip around the country,” Tom Petty told Rolling Stone last December regarding his 40th Anniversary Tour, which kicked off earlier this year. After four decades, thousands of shows and reaching “the back end of their sixties,” as Petty says, no one would fault the band if they decided to dial back their touring careers.

But whether or not this six-month, 46-city tour is indeed the last big run, these rock giants show no signs of slowing down—selling out arenas all over the country, night after night delivering a two-and-a-half hour showcase of heartland rock anthems that have formed the soundtrack to countless lives, closing each set with that ultimate sing-along, “American Girl,” giving fans one more chance to catch one of the greatest touring bands in rock ’n’ roll history.

Petty shows set a bar for high-tech audio production, thanks in large part to the efforts of longtime FOH engineer Robert Scovill, who has been mixing the band for nearly a quarter-century. For decades, Scovill has strived to bring studio-level audio production to live shows; however, things were a little different in 1994 when he got the call to work with Petty, who was gearing up to tour in support of Wildflowers. Back then, Scovill had a casual familiarity with the band, at best.

“During my first few days of rehearsals, I don’t think I heard a single Tom Petty song, just versions of cover songs,” Scovill recalls. “It was pretty apparent they were just getting loose and trying to simply reconnect with each other on this really, really cool level, and the music was the vehicle for it. This was so unlike anything I had been involved with, and I remember thinking, ‘Man, this is a gig I could stick with for a long time.’

“I think [Tom’s] relationship with me has developed over time to where he will ask my input on things now; things he certainly wouldn’t have approached me about in the first one or two tours that we did together,” he continues. “Not that he’ll always take my opinion, but he’ll certainly ask it now. I think it’s driven by the idea that I’m not going to lie to him, and I’m not going to fluff him up just because it’s his idea.”

“Robert is very much an artist himself,” Petty says. “He is the member of the band with no spotlight. If he doesn’t do an excellent job with the sound coming from the stage, the audience cannot receive an accurate account of what we’re doing. If the sound is bad, my performance was for nothing. Rob will not let that happen. His talent is such that he always delivers an exquisite mix that allows me to perform with the subtleties you need for a great performance. His job is very hard.

“He has made us grow into the reputation of having great concert sound, even in some very tough rooms,” Petty continues. “Because of his great experience on the road, he can tell us what nearly any venue sounds like. We consult with Robert on every gig we book. If he doesn’t think it can be made to sound good, we don’t go there. In my many years in this business, I have never met anyone who approaches the talent level of Robert Scovill.”

“We walk out knowing that we’re going to sound better than anybody has in that venue,” adds Heartbreakers keyboardist Benmont Tench. “And that’s big, because our band pays a lot of attention to the colors and shades in the tones of the instruments. Tom and Mike [Campbell] don’t just change guitars for the show, and I’m not running a used-keyboard emporium, either. We’re after something specific. And we know Robert will capture that.”

COVERING THE HOUSE

While Scovill has been the architect in the evolution of the band’s live sound, on this tour he is working hand in hand with Sound Image and a crack crew; tour production planning began in January, specing out system design and collaborating over the cloud via Evernote. Scovill provides his own custom racks of specialized ancillary gear, stored and ready to go at a moment’s notice.

The tour P.A. is an EAW Anya/Otto software-controlled system with customizable coverage capabilities to match venue seating geometries system (62 Anya boxes, plus 48 Anna for stadium-show delays; 13 Otto subs). “We used this system for the first time in 2014 on the Mojo tour,” says Scovill. “It is far and away the most ‘point-source’-like sounding multi-enclosure system I have ever worked on.”

Besides, Scovill says, this FOH mix is all about intelligibility and clarity, making sure Petty’s vocal cuts through and that all the other instrumentation sounds musical and has an energy that matches the moment. Petty, who currently sings into a Telefunken M80, is a relatively quiet singer, Scovill explains, which presents EQ and gain-before-feedback challenges. And The Heartbreakers are all about dynamics, he adds, which keeps him on his toes.

“In the course of ten minutes in the show, they can go from an acoustic kind of just tearing-your-heartstrings-out thing, which is very quiet and intimate, to Led Zeppelin on 11,” he says. “You’ve got to be prepared to handle that, and that really speaks to how I address some of the console architecture, in terms of how I emphasize some of their dynamics at times and de-emphasize their dynamics other times.

“But I can tell you, it is not a matter of just slapping on compressors and everything; that is not the answer,” he says. “The answer is in intense attention to detail and making fader moves, many times on the master fader, to make the dynamics of a given song work. There are times when we are just balls to the wall; there are times when we are intimate and spatial; there are times when we are mid-tempo, where everything has to be heard in place. You get the whole gamut in two hours in a Tom Petty show, for sure. Mixing is a verb!”

For frontfills, Scovill came up with an unorthodox way to provide directivity and localization in a challenging coverage zone, using a combination of small K-Array KRX 802 12-inch coaxial speakers (seven for arenas, 14 for stadiums) attached to EAW Otto DSP-controlled subs with custom brackets provided by Sound Image. Seven high-end “speakers-on-sticks” stations are distributed across the front of the stage to support the LCR configuration of the main P.A. system.

“I spend a lot of time down there trying to get that area to sound right and get it really in phase with the backline,” Scovill explains. “The Tom Petty stage is a very live and active stage; there are a lot of guitar amps, a lot of drums, a lot of piano and keys and stuff going on up there. So it takes some concerted effort to get that mixed correctly for that first four or five rows. From talking to Tom, he can see it in people’s eyes down there. If it doesn’t sound good, he can make eye contact with them and know that something is amiss. I remember being that fan down there, and I desperately want that experience to be killer.”

Petty tours have been carrying Avid Venue D-Show consoles since that product was released in 2005; on this run, they’ve upgraded to the Venue S6L. This latest version features new processing and workflow capabilities, including virtual soundcheck functionality designed in part by Scovill, who for the past decade has served as Avid’s Senior Specialist for Live Sound Products.

Scovill designed his virtual soundcheck process while in early rehearsals with Petty in 1994 and says he’s happy to see that experience come full circle. “That whole workflow was a survival mechanism for me with the Tom Petty camp,” he explains. “I just developed it over 10 years of using it, and through my work with Avid was presented an opportunity to get it into a product as an actual feature.”

One of the biggest benefits of virtual soundcheck is that, once mixers are able to focus on technique without anything “at stake”—meaning an audience in the room or a band onstage—they are free to grow in their craft. “Mixing the show is so much fun now,” says Scovill. “You can just stay focused on the music—not only refine the mixes, but start to refine your actual technique and skill. I have not seen the band in the building for soundcheck since 2005. To say it has positively impacted their touring lifestyle, and in turn, their longevity while on the tour, would be gross understatement.”

THE HEART OF IT

For Scovill, art and technology go hand in hand, and presenting that classic Heartbreakers sound means leveraging an analog soundscape with plug-ins and digital control. “From my perspective, the main attraction to digital was the accompanying plug-in architecture for digital consoles, the ability to build and emulate the analog qualities that my ears have been programmed to over years on the road and in the studio—but at the same time being able to take advantage of the programmability and system scale that digital offers,” he says.

“What really bugs me is when I hear my peers romantically extolling the virtues of analog as if it’s some sort of magic elixir,” he adds. “Or, worse yet, presenting it as a means to an instantly great-sounding show, the minute you turn it on. As a mixer, you still have to do the work, whether it is on an analog or digital system. It makes me crazy when I hear someone claim, ‘That show sounded great, and it was all analog,’ as if it could not have sounded as great if it was all digital. You can rest assured that it sounds great because the person behind the console is a master at his craft. The gear is simply a choice we make.”

MONITORING THE STAGE

Greg Looper has been touring with Petty since 2005, starting out as Scovill’s system tech and progressing to monitor engineer in 2009. He also has maintained a side gig as Petty’s studio engineer since 2009, recording the band live at their storage and rehearsal space, The Clubhouse.

On this tour, Looper mixes on an Avid S6L, and each bandmember has his own wedge mix, with Petty, Scott Thurston and Benmont Tench adding a single in-ear monitor in the ear opposite their wedge.

“They like the feeling of the isolation of the vocal in the in-ear, but the openness of hearing the rest of the stage,” explains Looper. “Scott and Benmont, it’s pretty much just vocals in their in-ear. There are a few instruments in Scott’s in-ears—guitar, a little bit of bass and drums, but not much. Most of it’s done with the wedge. The only things in Tom’s wedge are his vocal and his acoustic guitars; everything else is in his earpiece.”

Processing is minimal, Looper says, mainly some slight reverb treatment here and there and a 150-millisecond slapback on Petty. His main concern is latency: “As soon as they play a note, that note has to be right there; so it’s just trying to keep my signal path as short as possible,” he explains. “All of my processing has to be DSP console-based.”

Looper says he doesn’t worry about managing dynamics because the guys onstage essentially mix themselves, in relation to each other. “It’s jaw-droppingly amazing how good these guys are,” he concludes. “Most of the time, it’s just getting out of the way and giving them the things that they need.”

THE WONDER OF IT ALL

Reflecting on his long tenure on the road with Petty, Scovill says it can be difficult to contrast “then and now” ways of working, simply because the entire touring infrastructure is so much more mature than it was decades ago. “In the earliest days of this, it was totally flying by the seat of your pants,” says Scovill. “But at the end of the day, you still have to point the speakers at the people and you still have to make it sound good,” he says. “There’s better catering now, I’ll give you that.”

Scovill remembers stepping back from that first Petty encounter, all those years ago, and thinking to himself, “This might be the greatest band in America right now.” “I still feel like that today,” he says, adding a slight twist: “This is America’s greatest rock band, you know?”

THE VIRTUAL SOUNDCHECK SURPRISE

Scovill was doing analog virtual soundchecks with Tom Petty for many years before Petty was hip to the process—until one day in 2005. “When we moved to the Avid [then Digidesign] Venue D-Show console in 2005, I was in rehearsals at Sony; we had the P.A. and everything set up, just as we would do it for a normal show, and I came in early one afternoon and thought, I’m just going to go into playback, break everything down here, just check everything out and work on some sounds and mixes,” Scovill explains. “So I started doing this, and probably worked for two, three hours, with the P.A. at full volume, only at some point to turn around and realize that Tom was in the back of the room, sitting on a couch, taking it all in.

“You have that moment of panic, where you think, okay, what did he just hear me do to his music for the past two or three hours? I might just be out of a job here. But at some point, he came up to me and said, ‘I didn’t know you could do that. That might just be the coolest thing I have ever seen in my life. I have never heard what we sound like out front.’”

It was a moment of bonding, says Scovill. “I knew within 30 seconds of that conversation that what I had actually done was instill confidence in him in my abilities. But I also saw the light bulb going on over his head when he said, ‘Can you do this for monitors as well?’”

THE 57 INCIDENT

Trust takes time, as Scovill learned right out of the gate with Tom Petty back in 1994. “I was trying to get this vocal sound out of him singing into his then-iconic SM57 without the windscreen, and at that point, he was surrounded by four huge wedge monitors, no ear monitors or anything, and let me tell you, it was a real struggle.

“About three or four days in, I was kind of feeling my oats, and had already interacted with him on a couple of occasions, and felt pretty confident when I approached him and said, ‘You know Tom, I don’t know how married you are to the 57 here, but I’m pretty sure if we try a couple of different vocal mics, I could get a much better vocal sound than I’m able to get right now.’ Without even batting an eye—he didn’t even look up at me, I can remember it like it was yesterday—he had his hand up on the microphone and was kind of leaning on the mic stand and looking down, and he said to me, ‘You know, Rob, that’s what the last guy said right before he departed.’

“I instantly had this moment of, ‘You know what, let me just give that mic another try.’ I was able to get him to change that mic over time, but the lesson learned there was that respect is earned; it is not freely given.”