Philadelphia, PA—When the U.S. side of Live Aid kicked off at noon on July 13, 1985, the UK edition [See Part 1] had already been rocking for five hours—but given everything that happened before the Philly show even started, it was as if the entire production had been running a marathon for days.

Once the U.S. edition began, from there on out, performances would alternate between the U.K. show in London and the concert in Philadelphia’s JFK Stadium until the U.K. called it a day at 10 PM London time / 5 PM in the States, with the U.S. then continuing on until 11 PM. During the overlapping hours, broadcasters worldwide alternated performances between the shows, giving crews on each side of the Atlantic extra time to set up and tear down while the other continent’s acts were performing. However, just getting to that point was already an accomplishment for the live sound pros on hand, given that the entire gig had come on short notice.

“I think they were contemplating who’s gonna do the sound a week before,” recalls Roy Clair, co-founder of audio provider Clair Brothers (now Clair Global). “At that time, there were only two companies in America that could have done that show—us and Showco—and obviously sometimes it had a lot to do with how many of your groups were going to be on the bill. The promoter, Bill Graham, was open as to who was going to do the sound, but in the long run, it may have had to do with location, location, location, because we’re based in Pennsylvania. We’d like to think that it was because we were the best. I’m kidding, of course, but you know, it meant a lot to us because it was a huge show, there were a lot of groups on the bill, Live Aid went well and we actually gained some momentum because of that show.”

Inside the Live Sound of Live Aid, Part 1: London

It helped that the Clair team was familiar with JFK Stadium, having provided audio for a Peter Frampton/Lynyrd Skynyrd show there in 1977, but being picked as the sound vendor so late meant there was little time to prepare. “That is what we’re good at—getting a show together fast,” said Clair. Sound for 89,484 people? No problem.

A team of 12-15 pros from Clair loaded into the site three days before the show, and since there was little in the way of pro-grade audio equipment available commercially back then, virtually all of the sound gear was proprietary. That included roughly 120 Clair S-4 loudspeakers and eight prototype P boxes, powered by Clair’s Phase Linear 700B amplifiers. All that P.A. was loaded into scaffolding on either side of the stage, with long-throw boxes placed 50 feet up in order to hit the stands on the far side of the stadium. When it comes to recalling the front of house mixing position, memories and accounts vary, but there were up to six Clair CBA32 mixing consoles on-site, all summed into a Harrison SM-5 console that was used both as a matrix mixer and for media inputs from the White House, the Space Shuttle and other outside sources.

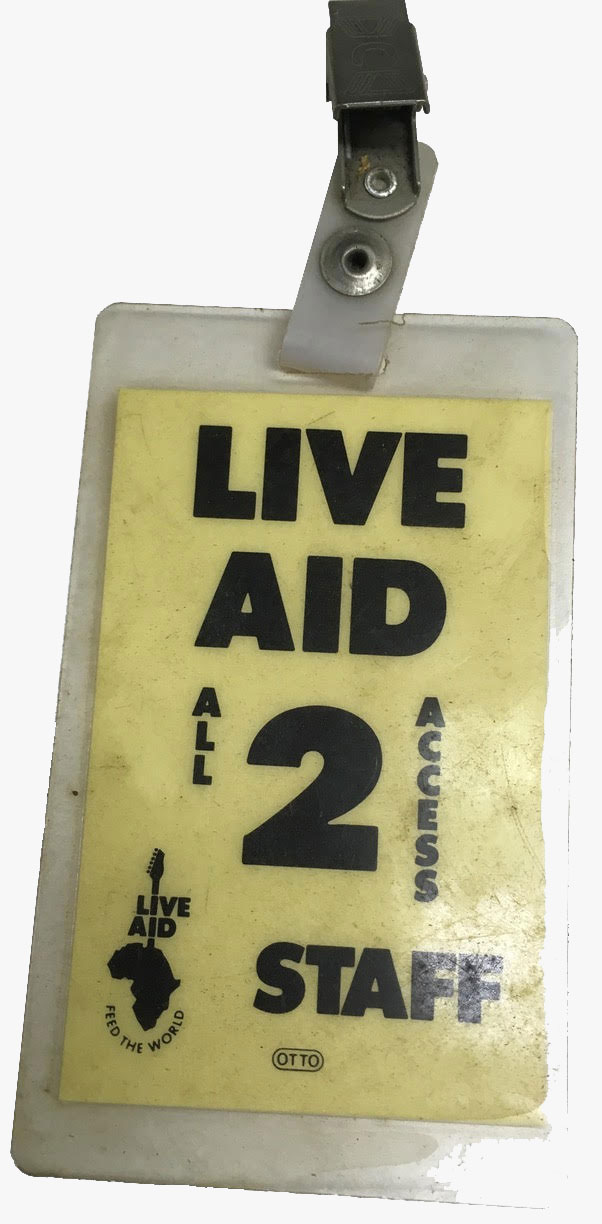

The Clair engineers weren’t the only audio pros who wound up at Live Aid on short notice. While today he’s a veteran sound engineer at Carnegie Hall with 20 years of mixing Broadway shows under his belt, back in July 1985, Andrew Funk was a 23-year-old tech who had been working less than two weeks at the Manhattan office of German pro-audio manufacturer Sennheiser. Two days before the show, Funk was told to bring his classic Cadillac convertible to the office, load up the trunk with wireless microphones and test equipment, and take it all to directly to JFK Stadium. “When I pulled up in Philly, everybody was like, ‘Who is this guy in the convertible?’” he remembers.

Funk and Sennheiser sales support pro Tony Cafiero set up their wireless receivers—EM1036 Rack Frames—at stage left behind the stacks. Normally six of the bulky receivers would have taken up eight rack units, but with rack space at a premium, only a few frames got racked, and the rest were simply piled atop a case next to them.

“These days, everyone would have their own wireless handheld,” says Funk, “but back then, it was very much magic when it came to wireless mics. There was no such thing as RF coordinators, there was no frequency agility; everything was on a set frequency, so if you had trouble, you had to actually get another mic. It was the very infancy of wireless microphones.”

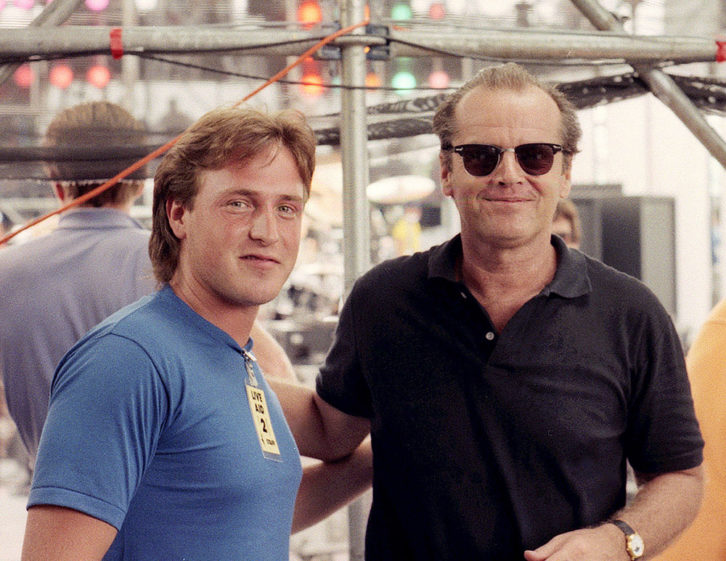

During the show, Funk’s job would be not only to babysit the receivers, but also hand-off the six SKM 4031 wireless handheld mics to musicians and celebrities like the show’s host, actor Jack Nicholson, and then collect the mics when they came back offstage. The significance of the concert quickly became apparent to Funk: “We got set up and they immediately went into rehearsals with Mick Jagger and Tina Turner, so right off the bat, with headliners like that, I got a nice introduction to what the show was going to be like.”

Also taking up much of the stageside area were multiple monitor mix positions, which were centered around two Harrison SM-5 consoles and a Midas Pro4 desk. In order to speed up downtime between performances, the stage itself had a rotating center turntable; while an act performed out front, the next act’s gear was set up in back and then rotated 180 degrees to face the audience when it was time for the next performance. As a result, the two Harrison consoles, used for different halves of the turntable, were located on opposite sides of the stage and were looked after by Clair’s Dave Skaff and Rick Coberly, who were the respective desks’ system engineers and monitor engineers for acts that didn’t bring their own. Meanwhile, the Midas desk, used for front-line duties like monitor mixes for presenters between acts, was overseen by Clair’s Henry Cohen (now senior RF systems design engineer at CP Communications).

As with any load-in, there were problems along the way, but a near-showstopper happened less than 24 hours before showtime. Skaff, who after decades of mixing monitors for acts like U2 and Led Zeppelin’s 2007 reunion is now part of Clair Global’s engineering design and tour support teams, recalls, “The night before the show, the turntable motor broke—it just burnt up and it was too late to take it out. Between Bill Graham and [legendary stage designer] Michael Tait, they decided it would have to be manually turned—but how? Tait came up with a great solution where they cut pockets around the turntable and put in these metal ‘receivers’ [where you could put in] a Schedule 40 aluminum pipe and now you had something you could push on. Well, they put about 20 of those in and then Bill Graham made a call to the Philadelphia Eagles and they had 20 guys over there as quick as they could get them. The Philadelphia Eagles’ defensive line came in and turned the turntable all day—that was pretty wild. That was one of the ones that impressed me the most, that we could get anything done that we needed.”

Spinning on that turntable, providing sound to the acts, were a slew of Clair LP floor monitor speakers, supplemented by flown S-4 loudspeakers at stageside. In-ear monitors, while commonplace today, were still in their infancy and wouldn’t go mainstream within live sound for another decade—but they were there at Live Aid.

Marty Garcia, founder of in-ear monitor pioneers Future Sonics, was on tour with The Hooters, which had three top-40 hits that year. Given that the group was from Philadelphia, it was quickly tapped to be the first band of the day, which meant Garcia’s in-ear monitors—a wired pair worn by drummer David Uosikkinen—were seen around the world and by curious artists backstage for the first time. “I was just finishing up a whole bunch of custom ear monitors when The Hooters got added to Live Aid,” Garcia recalls. “I said [to Uosikkinen], ‘Let’s get you on ears for this—that way, you don’t have to worry about not having a soundcheck long enough to get what you need. I’ll dial it in with the monitor engineer.’”

The Hooters’ set was significant for Skaff, too, as he’d become friends with bassist Andy King over the years as they both paid their dues in the regional club scene with a band called Jack of Diamonds. “That didn’t go, he ended up in The Hooters and now they were opening up Live Aid. So the two of us, standing on stage right before it started, was like kind of a ‘pinch yourself’ moment. It was pretty cool.”

The stage itself was a hectic place, but the audio team kept everything moving onstage. Key to that team was patch master Kathy Sander, who kept the show on-time for 11 hours, ensuring that every mic and DI box was correctly patched not only for the show onsite, but also for the multitude of radio and TV broadcasters as well.

“As soon as somebody went on stage, I would hold my breath for about a minute,” she says. “If there were any microphones not working, that’s when you would hear that something needed to be addressed. Then I was already starting soundcheck for the next act in the back.”

Every artist wanted more than the standard allotted 17-minute set in front of 1.9 billion people watching worldwide; add dozens of celebrities introducing acts, endless crates of gear and massive egos to appease, and the show was practically guaranteed to not run on time—and yet it did. “How the sound engineers coped with the amount of bands and changeovers on the day is beyond me,” recalls Midge Ure, co-founder of Live Aid. “The equipment, monitor and FOH boards, albeit the best available, were analogue so there were no preset patches or recall available. It was old-school ‘flying by the seat of your pants’ mixing.”

That kind of mixing was necessary, too, because even when the audio team knew what was happening next, there were still surprises—like R&B legend Patti LaBelle. “She came out and literally blew the console apart,” laughs Skaff. “Before she went on, we did as much as we could to turn the damn thing down and pad it down, and [late tour director/production manager] Mo Morrison said, ‘That ain’t gonna be enough.’ I’m like, ‘Why not? There’s no—’ and she just lit the desk up red! The whole stage was her voice, dialed up through all the monitors. It was like the voice of God was there that day, and it was Patti LaBelle!”

While MTV broadcast the entire show, ABC aired the final three hours live starting at 8PM, which meant that the concert had to be running on time to the split second, eight hours after it started. “England was running so far behind schedule that it didn’t quite work out the way ABC wanted it to, but we were on time—I was so proud of that,” says Sander.

It was no simple accomplishment, as bands wanted all their usual touring gear set up, regardless of whether they needed it for their set. “Bands wanted to have people be impressed by their gear and their performance, because this wasn’t just putting on a performance for charities—it was exposure,” says Sander. “So the TV mixers, they’d be looking at their screens, see a synthesizer that’s not being used at all, and then call up and say, ‘Hey, I don’t have the synth [in my inputs]!’ That’s because they’re not playing it.”

The U.S. show closed out with all the artists back onstage for a massive sing-along of the USA for Africa charity single, “We Are the World,” and that moment summed up the day for Sander: “The thing that I remember the most was running out to line up microphones across the front of stage, and then going over to the side, looking at my watch and it was just right at 11 o’clock, which was our end time. I was so relieved because we hit it on time, and watching all those artists perform ‘We Are the World’ was awesome. And as soon as I realized that it was essentially over except for the rest of the song, I had a migraine. That’s how stressful it was. I recovered from that nicely, but it was just shocking to me.”

For Sennheiser’s Funk, the grand finale was his most memorable moment, too—because the show nearly ended in disaster.

“During ‘We Are the World,’ all of our wireless mics are out there on the stage,” he says. “I’m off to the side at stage left behind the stacks and the two wireless racks are right next to me—one is in the case and the other one isn’t.

“All of a sudden, I start feeling water or something dripping from overhead. I look up and there’s this stage guy up on the scaffolding watching the show and he has this big can of beer. It’s the biggest can, too—like a Colt 45 or a Fosters. The can’s in his shorts and the thing’s pouring out directly into the wireless rack frames. The show’s going, the beer is pouring in, the wireless is going and I’m like, ‘Those mics are going to go dead on the final song of the night!’ I’m yelling up to the guy and there’s no way he can hear me over the show. Myself and Roy Clair from Clair Brothers start throwing things up at him to get his attention. Doesn’t work and the beer’s just pouring out. And you know what? The mics didn’t stop at all—even with the beer, they still worked, still made it to the end. I thought that was pretty cool.”

Whether good fortune, German engineering or outright divine intervention, the result was a grand finale that’s remembered for all the right reasons, bringing to an end a momentous, landmark day that even decades later, all the production pros involved still see as a highlight of their careers.

Clair Global • www.clairglobal.com