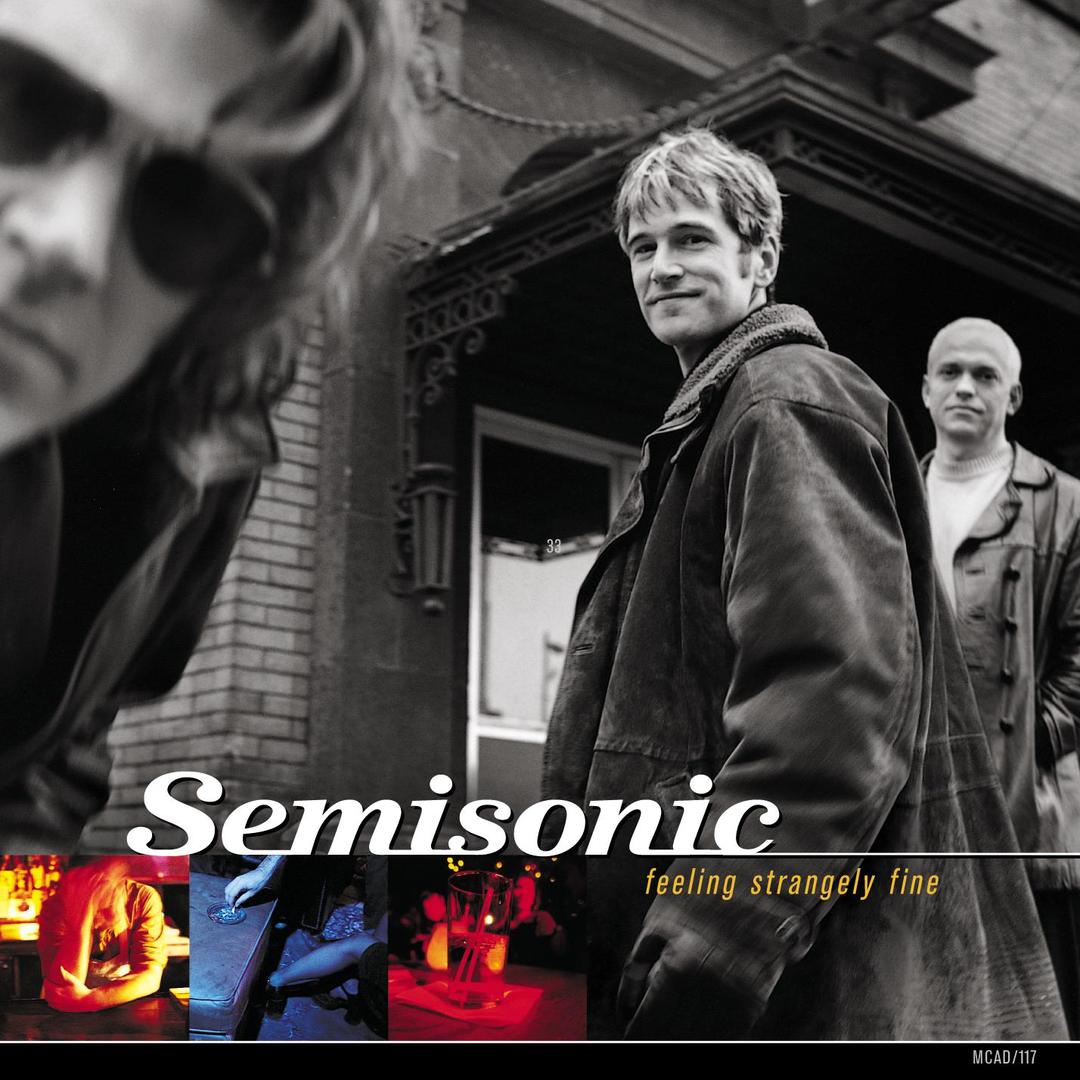

If it had not been for producer Steve Lillywhite, Semisonic’s Feeling Strangely Fine and its hit single “Closing Time” would never have seen the light of day. This little-known fact takes on more weight considering that Lillywhite had absolutely nothing to do with the making of this record.

The producer was walking the halls of MCA for meetings when he heard “Closing Time” coming out of one of the offices and inserted his opinion about what a hit it was. Semisonic’s album had already been rejected by the label. Lillywhite had saved the day.

That was only the final spin on the roller-coaster ride that was the production of that album and that track.

Producer/engineer Nick Launay, living in Sydney, Australia, at the time, met with the trio—songwriter/vocalist Dan Wilson, drummer Jacob Slichter and bassist John Munson—in Minneapolis in 1998 and instantly bonded with them. “I remember I really liked them and didn’t want to leave,” Launay recalls. The project was set to begin in six months, but a week prior to Launay’s flight to Minnesota, Wilson’s pregnant wife gave birth to their daughter prematurely.

Amid the emotional pressure of the situation, “Closing Time,” which was never intended as a drinking song but rather was about destiny and the anticipation Wilson felt regarding fatherhood, took on an even larger meaning to the songwriter.

Seedy Underbelly Studio in Minneapolis had already been booked, and as no one knew how it would play out, Launay was told to come anyway.

Launay loved the studio—all wood, oranges and browns, with lampshades instead of overhead lighting. The owner, John Kuker, with whom he became great friends, had stellar equipment, starting with an API desk and lots of vintage microphones, rare guitar amps and, of course, guitars.

Interview with Nick Launay

“I work with a lot of very chaotic, eccentric bands,” Launay says. “This band was very organized and planned ahead, but had a very good understanding of what good rock music is and that it has to be spontaneous. I think they had demoed their previous record to death and then gone in to re-create it and realized that doesn’t always work very well. They wanted to write the songs in rehearsal and then go in with a record producer who knew how to capture feeling and vibe and excitement and euphoria. I work with Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, and there’s no demoing. Half the band has never heard the songs and they’re recorded very quickly. We recorded 24 songs in 12 days.”

He believes some bands hire him to discipline the chaos, but he suspects Semisonic hired him to create a little.

Launay says that unlike a lot of record producers who are musicians, he came from an engineering background. “I’m all about microphones, I’m all about equipment. I was the geekiest kid imaginable,” he says. “I started messing around with tape machines when I was 7 or 8. I just love equipment and sounds.

“The first record I made was with Public Image, called Flowers of Romance, and I worked with Kate Bush when I was 21 years old,” he continues. “If you listen to those records, they have really crazy sonic landscape. That’s because I was this hyperactive kid at that age who was allowed to use this great recording studio in London and I just went wild.

“So that’s where I come from. I did realize early on that I do have a really good sense of songs and songwriting and arrangement, and it’s easy for me to hear a song and say to a band, ‘This bit is really great and this bit really doesn’t do much, and maybe the middle section of the song is a catchier thing and should be the chorus.’”

On “Closing Time” in particular, Launay says, the guitar sound had to be established as soon as the track began.

Classic Tracks: Supertramp’s “Give a Little Bit,”

“‘Closing Time’ has got a great guitar riff, so obviously the guitar sound was very important,” he continues. “It was very important that the drums grooved. Jacob is a phenomenal drummer, an incredible timekeeper. Drummers can lean one way or the other as far as groove—be absolutely spot-on like a machine, which is what you might want with dance songs, but with rock music, you might want it to have some swagger or lilt, a more kind of Charlie Watts, Stones kind of feel. Jake was very capable of doing either. On that song, I really wanted it to slow down and speed up and have momentum. If you listen to it, you’ll see how the verses are very chill and very relaxed and behind the beat, and on the chorus they’re pushing.”

The song was recorded to a click—one speed for most of the song, then deliberately sped up 1 bpm for last chorus out. They tracked live, including vocals, on analog tape (Ampex 499) to a Studer A827. It was 1999. They didn’t use a DAW.

“We tried to keep everything to 24-track, so sometimes some tracks had two or three different instruments on them,” Launay explains. “On ‘Closing Time’ we did run out, in the end, when we decided to add real strings, so we added a slave reel.”

The drums were slightly closed off in the back of the room behind a glass door, but everybody remained together in the room. “They could all see each other and they all had their own headphone mixes,” Launay says. “The guitar, bass and drums were all recorded on the same take. There are no overdubs.”

For Wilson’s vocal, he used a Neumann M49 through a Neve 1081 through a Tube Tech CL1B compressor. He used a Roland Space Echo for effects. He says he believes the original vocals they cut live were the ones they kept.

Detailing the miking of the drums, Launay says they were all through the API Legacy with 550B 4-band EQs, except where indicated: Kick inside was a Beyer 88 through a Neve 1081 pre; kick outside was a Neumann U47; snare top, Shure SM 57 through a Neve 1081; snare bottom a Sennheiser 441; hi-hat, Neumann KM 84; toms x3 AKG 414; ride cymbal, Neumann KM 84; left cymbal, Neumann KM 84; right cymbal, Neumann KM 84; room mic left, a Neumann U 87 (not tube, “compressed to death through a UREI 1176”); room mic right, a Neumann U87 (not tube, “compressed to death through a UREI 1176); distant room mic, Shure SM 57 (“compressed to death through a Shure Level-Loc compressor”).

“The snare Jake used on the song was a unique Keplinger made out of an iron sewage pipe,” Launay says after making a call to Slichter. “We also deliberately had a row of other snare drums rattling in the same room. Jake remembers there was a Coles 38 ribbon mic dangling just above his head with a sticker on it saying, ‘Don’t hit this one.’”

Classic Tracks: “I’ll Be You,” The Replacements

Launay close-miked the bass with a Sennheiser 42 and used a Shure SM7 as the room mic, plus a tube DI, all through the API. He placed two mics on the guitar amps—a Beyer 88 and AKG 414—and one distant mic, a ribbon RCA 77, about three feet away, all through the board.

Later, bassist John Munson also played the piano part on what they recall as a dusty old upright grand piano from the 1900s sitting unused in an antique shop next to the studio.

“We didn’t even tune it—great sound, though,” Launay says. “Just the right amount of rickety. It was miked with one Neumann tube 67 through UREI 1176 compressors through the API.”

They also added a combination of real strings (four violins, a viola and cello), a string patch on a Kurzweil 2000, and some untuned Mellotron samples that Launay recorded in Australia from Midnight Oil’s Jim Moginie’s real Mellotron. Launay says he recorded many takes and he edited between the takes.

“I’ve always done a lot of editing. It was probably around the tenth take we chose, and I think the middle section and outro we were going from, apart from the very end when it drops down again, which was from a separate take that was a little more rowdy. We would do a take of the song really chill, and then a take that was really rowdy, and I would chop between them for the different sections. It’s basically going from Simon & Garfunkel to The Who.”

Jack Joseph Puig mixed the track. “I usually mix my own stuff and was very apprehensive about somebody else mixing what I had done,” Launay recalls. “Jack did a really, really great mix.”

Interview with Jack Joseph Puig

The album was delivered to MCA and was rejected on the grounds that they could not hear a single. They told Wilson the band needed to go back into the studio to record four more songs.

“The band was beyond disappointed and couldn’t believe what was happening to them, having watched other bands being dropped,” Launay says. “There were lots of meetings from management, and I got a call from the band, whom I had become very good friends with, and Dan had become convinced that the only solution was to go back in to record four more songs.”

Launay refused to do it. He explained to Wilson that it would only result in heartbreak, that the album was great as it stood and “if this record company could not hear that there were three hit singles on this record, they were never going to be able to hear.”

Classic Tracks: Yes, “Roundabout” and “I’ve Seen All Good People,”

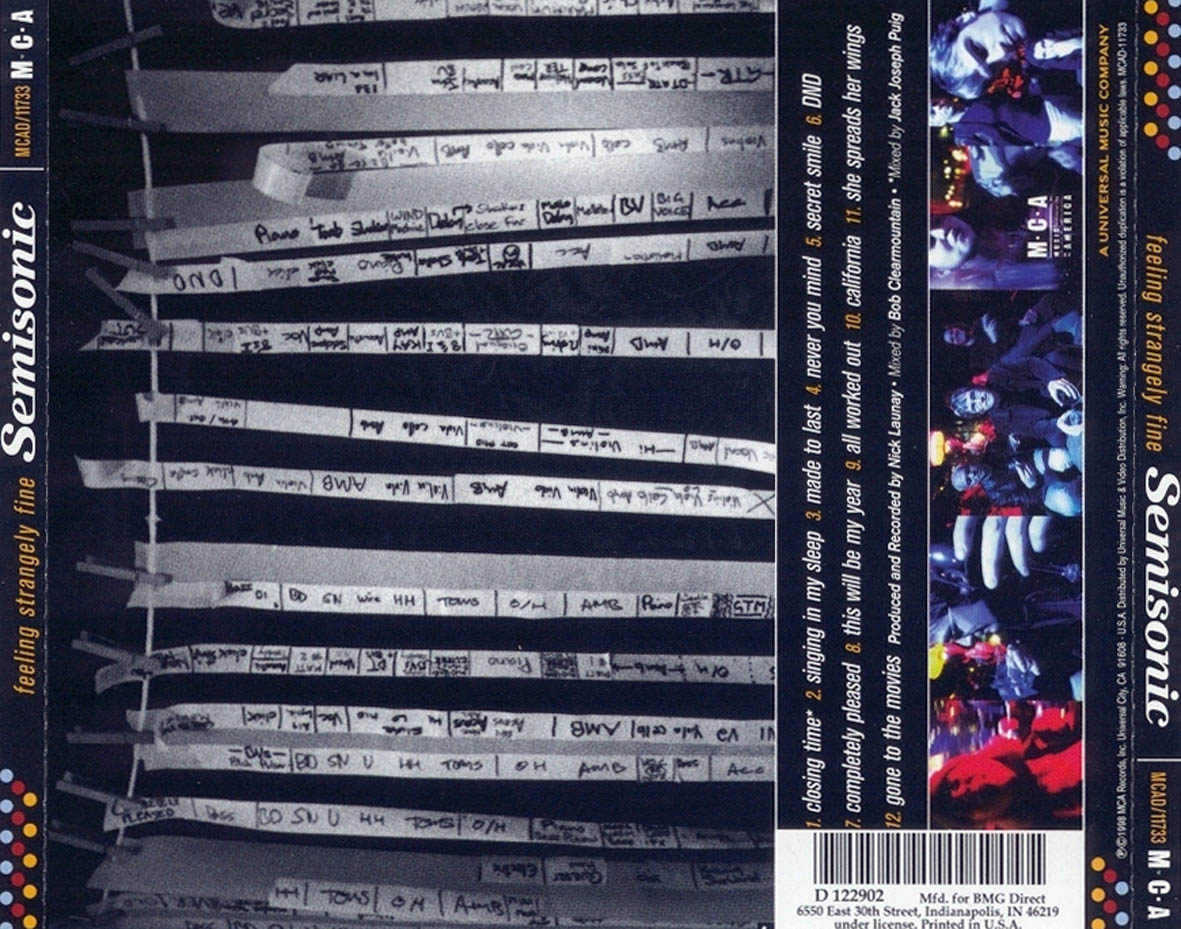

It turns out there were three hit singles on the record: the Grammy-nominated “Closing Time,” which hit Number 1 on the rock charts; “Secret Smile,” Top 30 on the rock charts; and “Singing in My Sleep,” Top 40 on the rock charts.

And lo and behold, MCA is in the process of re-releasing Feeling Strangely Fine to celebrate its 20th anniversary. Thanks, Steve Lillywhite.