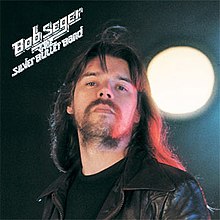

“Night Moves” was a good move for Bob Seger. The song — both the Number One single and the title track of the Capitol Records album released in October 1976 — solidified his place as one of the premier “heartland” rockers, along with Bruce Springsteen and John Mellencamp, creating what was essentially a new genre in the rapidly fragmenting American music industry. The same album also contained the singles “Mainstreet” and “Rock and Roll Never Forgets,” and their success paved the way for Seger to expand on these themes — lyrically, musically and emotionally — to create a body of work that includes such Classic Rock K-Tel compilation staples as “Against the Wind” and “Stranger in Town,” right through the ubiquitous “Like a Rock,” which quite possibly has sold as many Chevy pickup trucks as it has records.

Like many of the records that have been profiled in “Classic Tracks” before it, “Night Moves” was largely spontaneous — the result of the last-minute need for one more song while fate or the A&R department is breathing down the artists’ necks — and it nearly didn’t happen at all, with luck and circumstance having as much influence as talent and persistence. Seger’s own career up to this point had mirrored that situation. He had given up on music at least once before, after stunted attempts with such bands as the Beach Bums and Doug Brown & The Omens on the college-heavy Detroit/Ann Arbor circuit in the 1960s. There had been a couple of minor successes for Seger on the local Cameo label, and his first solo band, the Bob Seger System, was signed to Capitol Records briefly. Still, that wasn’t enough to keep Seger from throwing in the towel in 1969 to attend college.

But Seger couldn’t stay away. After restarting his career in 1971 and assembling the Silver Bullet Band, a live double-album, recorded in Detroit, coupled with three years of relentless touring, gave him a new launch pad. Capitol Records was again interested, based on the success of the Live Bullet album, but wanted to hear what Seger’s studio efforts would produce.

Jack Richardson was a Toronto native whose career had interesting parallels to Seger’s; he, too, pursued a career as a musician in his youth, only to move into advertising in his thirties to support a family. He took a flyer on a Canadian rock band called the Guess Who, mortgaging his house to pay for their first major label record, which he produced. With hits like “These Eyes” and “American Woman” under his belt — records by a Canadian band, which, ironically, presaged the Americana music movement that Seger would champion — Richardson quickly attracted other production clients, including Poco, Alice Cooper and Manowar. In early 1976, Richardson was approached by Eddie “Punch” Andrews, Seger’s manager and former bandmate in the Detroit trio The Decibels, about producing four sides for his client. Richardson thought the talks had been vague; Andrews apparently felt otherwise. “I came home from off a long date in L.A., and my wife says to me, ‘Punch called and says you’re supposed to be in Memphis with him and Bob Seger,’” Richardson recalls. “I said, no way, not on that short notice. So we talked again, and again it seemed to go nowhere. On four occasions, I was booked to meet with [Seger], and each time it got put off, once when I was already at the airport. Then I get a call one day telling me they’re coming to Toronto. That wasn’t the way I liked to do things. But I went ahead and called [engineer] Brian Christian, who had worked with me on the Guess Who and other records, to come in from L.A.”

Jack Richardson was a Toronto native whose career had interesting parallels to Seger’s; he, too, pursued a career as a musician in his youth, only to move into advertising in his thirties to support a family. He took a flyer on a Canadian rock band called the Guess Who, mortgaging his house to pay for their first major label record, which he produced. With hits like “These Eyes” and “American Woman” under his belt — records by a Canadian band, which, ironically, presaged the Americana music movement that Seger would champion — Richardson quickly attracted other production clients, including Poco, Alice Cooper and Manowar. In early 1976, Richardson was approached by Eddie “Punch” Andrews, Seger’s manager and former bandmate in the Detroit trio The Decibels, about producing four sides for his client. Richardson thought the talks had been vague; Andrews apparently felt otherwise. “I came home from off a long date in L.A., and my wife says to me, ‘Punch called and says you’re supposed to be in Memphis with him and Bob Seger,’” Richardson recalls. “I said, no way, not on that short notice. So we talked again, and again it seemed to go nowhere. On four occasions, I was booked to meet with [Seger], and each time it got put off, once when I was already at the airport. Then I get a call one day telling me they’re coming to Toronto. That wasn’t the way I liked to do things. But I went ahead and called [engineer] Brian Christian, who had worked with me on the Guess Who and other records, to come in from L.A.”

Seger and Richardson met at Soundstage, the producer’s studio within the production complex Nimbus 9 that Richardson and three former advertising business colleagues had formed in the late 1960s in Toronto to pursue music and commercial projects. Seger and Richardson sat in his office, and the artist played a couple of songs that Richardson recalls as being “not that great, quite honestly. Then I suggested that we also do the old Supremes song ‘My World Is Empty Without You, Babe.’ So that was three songs. And Bob had been noodling around on the piano in my office, and I told him I thought he had the makings of a good song there, though he didn’t feel the same way at the time.”

The sessions were scheduled for three days, with members of the Silver Bullet Band having flown in, and the first three songs went down quickly, though without much passion. In fact, finding the fourth song had become such an apparent lost cause that Richardson sent the band’s guitar and keyboard players back to Detroit.

As it turned out, however, Seger’s noodling had evolved into a song, and with Richardson’s prompting, he and Seger cobbled an arrangement to it in the studio, where the remaining musicians — including Silver Bullet drummer Charlie Allen Martin and bassist Chris Campbell — had been quickly complemented with two last-minute local players, Doug Riley on organ and Joe Miquelon on electric guitar.

“The whole arrangement came together in the studio,” Richardson recalls. There, Richardson sat in the middle of the studio with Seger and the band, running the newly minted “Night Moves” down, making decisions such as the addition of an acoustic guitar-and-vocal breakdown in the middle of the song, while Christian — assisted in part by Richardson’s son Garth, who has gone on to rack up his own significant engineering credits for Rage Against the Machine and Red Hot Chili Peppers — ran the custom Audiotronics console and 3M 79 16-track 1-inch multitrack deck running Ampex 456. Monitoring was through a pair of Super Big Reds loaded with Altec speakers and a Mastering Lab crossover, driven by 60-watt stereo Citation amps, which Richardson admits were pretty underpowered but he felt sounded best with the speakers and room.

The track is sparse — bass, drums, acoustic and electric guitars, piano and a Hammond C-3 with a Leslie speaker cabinet. The drum kit was miked using a Shure SM57 on the snare and a pair of Neumann U67 tube microphones as overheads. The guitar amp had an SM57 close in on the speaker cone, a Sennheiser 421 near the outer edge; the acoustic guitar, which Seger played as an overdub after playing the acoustic piano on the basic track, was recorded with one of the six KM84 microphones that Richardson personally owned. The piano was miked with a pair of U67s in an overhead-V configuration; the Leslie cabinet had a Sennheiser 421 on the bottom rotor and two U67s on the top rotor. When the “record” lights went red, Richardson was in the control room tapping a pencil on an SM53 as a metronome. “It was sparse, but I looked at Bob as a kind of a street singer,” Richardson says. “The delivery of the whole track needed to be kind of raw. It wasn’t a matter of reflecting the needs of this one song; it was about reflecting the way Bob comes across.”

Classic Tracks: The Clash’s “London Calling”

The lyric inspiration, Seger once said, came from his youth: “I was shy; super shy. And I happened to fall into a faster crowd than I’d ever been in before. Because I played music, I was sort of a gimmick for those guys. And I got to meet the really ‘hot’ chicks, and I had my first great love affair, which is what ‘Night Moves’ is about; it’s about that girl. You know, the girl with the big breasts that we all went kazappo for when we reached puberty. It was a really mad, crazy affair. The album as well as the song were inspired by American Graffiti. I came out of the theater thinking, ‘Hey, I’ve got a story to tell, too! Nobody has ever told about how it was to grow up in my neck of the woods.’”

The basic track for “Night Moves” went down in fewer than 10 passes on the last day of tracking for the entire four-song project — and that was allowing, Richardson reminds, for the fact that two of the bandmembers were no longer there. “There was definitely some time involved for the band and the studio guys to get their communication together,” he says. The bulk of the song was cut, the session was suspended while Seger recorded the acoustic guitar interlude, then the band resumed for the big finish. The three parts would be spliced together by Richardson and Christian on the 2-inch tape after the vocals were done.

Seger sang into a U67, as did the three hired female background singers who come in only on the tag. The vocals were recorded virtually flat. “I’m not one for playing with EQ,” Richardson says. “I’d rather spend the time finding the right microphone and getting the right setup for the singer. In this case, I pushed Bob up a very little around the 1.6 to 1.8kHz range to accentuate the harmonics in his voice. He’s already got plenty of power in the high end. I think if you have to add more than 2 dB of EQ to anything, you’re in a salvage situation.” Drums and vocals got a touch of Teletronix LA-2A, as did the final mix. Richardson was prepared to do several tracks of lead vocals and comp them later — the sparseness of the track had left him plenty of media real estate to play with — but Seger got it on one track within five passes through the song. The mix was done that same day, spruced up with echo from EMT stereo plates and little else.

As good as “Night Moves” was — and Richardson thought it was an obvious single — the song still had to contend with the fickleness of fate. After Seger and crew left, Punch Andrews called to say that he was less than pleased with the mixes, and then phoned again weeks later to say the record company felt the same way. Richardson recalls being annoyed by the comments. Three months later, John Carter, an A&R person for Capitol in Canada, stopped by the studio. Richardson asked him how he had liked the Seger mixes. “He ducked the issue a little, but then said he thought that both tracks were pretty good — for B sides,” Richardson remembers. “And I said to him, ‘Both tracks? There were four songs! Would you like to hear the others?’ So I played him ‘Night Moves,’ and he really liked it. I made some suggestions for editing it down for a single.” The original mix had come in at over five minutes long; the single, after mastering and editing by Wally Traugott at Capitol, is three-and-change and radio-friendly, as they used to say.

Weeks later, on a break for a session producing the Brecker Brothers in New York, Richardson opened Billboard and saw “Night Moves” hit the charts at 95. He also noticed that the credits read it had been produced by Punch Andrews. He made a call to Capitol, but the next week, as the song began to rocket up the charts, the credit remained unchanged. The normally avuncular Richardson went ballistic. “I called John Carter and told him you’ve got 24 hours to get the credits right,” says Richardson. The next issue, it read “Producers: Jack Richardson and Punch Andrews.” “Punch wasn’t even at the sessions,” Richardson adds with a chuckle.

“Night Moves” hit the Top 10 (making it to Number 4) and remained there for several weeks. “Like all records, it’s a concoction of how people were feeling and thinking at a moment in time,” Richardson sums up. “And like a lot of hit records, it came together fast — the song and the record. There wasn’t a lot of time to spend screwing it up.”