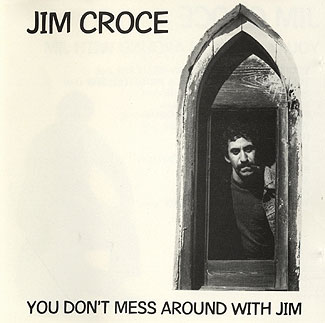

It was a life cut tragically short and a song that eerily captured the meteoric rise and brevity of its author’s career. “Time in a Bottle” reached the top slot on the pop charts in December 1973, but this posthumously released single was not Jim Croce’s only Number One record, as his producers Tommy West and Terry Cashman vividly recall.

West was a senior at Philadelphia’s Villanova University in 1962 and in charge of the university’s Glee Club auditions when he first met Croce. “I interviewed Jim, and after the audition he invited me to his house for dinner. We became close friends. He graduated in 1965 and our paths crossed a few years later in New York City. Jim’s stuff was okay, but not that good, to tell you the truth, until he hooked up with Maury Muehleisen a few years later.”

A classically trained guitarist and singer who was a student at Glassboro College at the time, Muehleisen, according to West, played a huge role in Croce’s success. “Maury was a genius, the best guitar player I ever heard. Terry and I produced a record of his on the Capitol label, but it didn’t go anywhere. He had a high, clear voice, like a male Joni Mitchell, and his ability to develop guitar parts that fleshed out Jim’s songs was extraordinary.

“The sound of their two guitars was extremely important. Jim played a Gibson Dove guitar that he’d actually given to me in the ’60s. It was a terrible-sounding instrument! I brought it to a guy named Phil Petillo who had a shop in New Jersey, and he shaved the bracings to make it sound brighter. Maury played two Martins: a D-35 and a D-18. The sound of the Dove and the Martins was gorgeous. I still get e-mails from around the world asking me how we got the sound of those guitars.”

Engineer Bruce Tergersen also played a critical role. “We recorded all of Jim’s stuff at the Hit Factory [starting with the 1972 album, You Don’t Mess Around With Jim], which Jerry Ragovy owned at the time,” West continues. “Jerry assigned Bruce to our original sessions, but at first it seemed an odd marriage. Bruce had worked under Tom Dowd, but he’d never done an acoustic record. He was a rock and R&B guy, and he seemed a bit odd to me. He didn’t talk much, but whenever we needed a sound, he’d play around with the patchbay and come up with something fantastic. I remember asking him at one point if he could make-believe the acoustic guitars were electric and process them in some special way. I don’t recall exactly what he did, but the color was gorgeous. I don’t think there have been any acoustic records that sound better than Jim’s.”

Cashman also remembers Tergerson quite well. “Ours was a match made in heaven — or hell — I never figured out which! Tommy and I weren’t into the hippie kind of thing. We loved folk music, and Bruce was just the opposite. On our first session, in walks this guy with flowing red hair who was clearly into the electric group sound. Bruce brought something different to acoustic music. He had a wonderful way of miking guitars, and he insisted on keeping a tuner in the studio to make sure the players were always in perfect tune.”

The rollicking title track off of the 1972 album You Don’t Mess Around With Jim established Croce as an artist with broad appeal, but West feels that the tender “Operator (That’s Not the Way It Feels),” off of the same album, was the best record they made. “That track established Jim as an artist, which was important to developing a serious, long-term career at that time. It wasn’t just a clever piece of writing, which Jim was obviously good at; it was thoughtful and heartfelt.” Less noticed on the album at the time of its release was another beautiful ballad, “Time in a Bottle.”

No one in the production team ever thought that song was going to be a hit. “No way,” says Cashman. “It was a waltz! We wanted to keep it simple, with Jim singing and Maury playing — that’s it. But we stumbled over a harpsichord that was sitting in the Hit Factory, and Tommy was intrigued about the possibility of adding it to the record.”

“That’s right,” says West. “The Hit Factory had a special vibe at the time. Jerry Ragovy was a great songwriter. ‘Time Is On My Side’ is one of his compositions, and the Hit Factory always had creative people coming and going. We had recorded at Jerry’s older studio on 47th Street, and when he moved over to the new facility at 48th Street we worked there. The console was custom-made by Lou Gonzalez, who later put Quad Sound together.

“To tell you the truth, the drum sound at the new Hit Factory wasn’t the best. But Bruce could make anything sound great, and he was open to ideas. I remember that he tried using a condenser mic on the Dove guitar, but we all agreed that it sounded dumpy. I played him some of the demos we’d cut and he asked what microphone I’d put on the guitar. I told him it was an Electro-Voice RE15 and he had me go back to my office and retrieve it. We used it on all of the tracks from that point on. It’s now hanging on my studio wall! Bruce used either a [Neumann] 87 or 47 on Maury’s guitars. I also remember that we tracked the first album on a Studer 16-track 2-inch machine, but the last two were tracked to Studer 24-tracks. We used Dolby on all of the tracks other than the drums — I liked the brightness of the drums when they were cut without Dolby.

“Actually,” West conitnues, “‘Time in a Bottle’ was originally cut on an 8-track machine. We didn’t think we were going to need any more tracks than the ones required to cut two guitars and a vocal. We transferred the originals to the 16-track machine simply because everything else was on 16-track tape.

“The night before we were going to mix, I was watching a horror movie on TV, and something must have lodged in my brain because when I walked into the studio the next day, I saw this harpsichord sitting in a corner and got an idea. A jingle company had used it on a session and in walked a couple of guys from SIR [Studio Instruments Rental] to haul it away. I asked them to take a lunch break and told Bruce to put a couple of mics on it. He was whining that it was out of tune, but I asked him to let me try something. I added two tracks of harpsichord, told the movers they could remove it, walked into Jerry’s office and asked if I could borrow the electric bass that was sitting on his couch, played that on just the second verse and the outro, and that was that! Radio compression worked in our favor on that record. It made the harpsichord blend with the two guitars in an unusual way. But we thought this record would only be an album cut.”

Things were moving fast for Croce, Muehleisen and the production team that had helped make them a ubiquitous presence on AM radio. “In July of 1973, ‘Bad, Bad Leroy Brown’ [from the album Life and Times] hit Number One,” says West. “‘I Got a Name’ [written by Norman Gimble and Charlie Fox for Last American Hero, a film starring Jeff Bridges] was about to be released, and Jim and Maury are stars with an international fan base.”

It ended in a flash. On September 20, 1973, Croce, Muehleisen, several other passengers and the pilot at the controls of the private plane that was shepherding them between gigs died when the aircraft failed to gain sufficient altitude and crashed into a pecan tree located just off of the runway outside of Natchitoches, La.

At the time of their deaths Croce, Muehleisen, West and Cashman had been working on a third album, also called I Got a Name. Posthumously released hits include the title cut, “Workin’ at the Car Wash Blues,” and “I’ll Have to Say I Love You in a Song.”

A week before the crash, producers of a now-forgotten ABC-TV Movie of the Week called She Lives! (starring Desi Arnez Jr.) featured “Time in a Bottle” in the soundtrack. The following day, radio stations across the country were bombarded with callers asking who sang the song and where it could be purchased. Although Croce was aware that the song had piqued the public’s interest, “Time in a Bottle” did not reach Number One until three months after Croce’s death.

More than 35 years have passed since the accident, and both West and Cashman have both enjoyed success beyond that early phase of their careers. But the pain of that loss is still great, particularly for West, who had a special friendship with Croce. “It still affects me greatly,” he says. “There couldn’t be a more melodramatic story. Here were two guys about to go over the rainbow, and it ends in an instant. I still have days — particularly when the leaves are changing color — where I sit and cry. I saw a rerun of an old Midnight Special show several years ago. There were the three of us, playing onstage, and I thought their deaths was a dream.”

West, who went on to produce successful records for Anne Murray and many other artists, operates a studio on his property in the farm country of New Jersey. Cashman, a former minor-league pitcher, eventually married his two passions and scored a major hit with the record Talkin’ Baseball, his 1981 tribute to the game he loves. Once Upon a Pastime, a musical he’s co-writing, is currently being given a reading at the York Theater in midtown Manhattan.

Croce’s music is still around, too, helping define a transitional era when the strains of Hootenanny populism mingled with power chords and electric technology. He was an heir to Woody Guthrie, a tributary to the great river of American music.