In this Amy Winehouse, post-Kurt Cobain era, it may be hard to imagine a day when ingesting illegal drugs was not de rigueur. Back in the mid-1960s, however, drugs were still just beginning their tiptoe march toward the broader youth culture. While many people slapped on a cooler-than-thou front, it often masked an understandable fear of the unknown. Leave it to sardonic songwriter Randy Newman to roll all of it — the excitement, apprehension, the unshucked need for parental approval — into one giant spliff of a pop song. Newman, whose quirky performance style would eventually bring the talented writer hits of his own, was unable to make a dent with “Mama Told Me Not to Come” when he gave it to The Animals to record in 1966, and his own version four years later fared no better. For another group, however, the song became a vehicle to superstardom. With Cory Wells handling the lead vocal, “Mama” was the first Number One hit for L.A. band Three Dog Night.

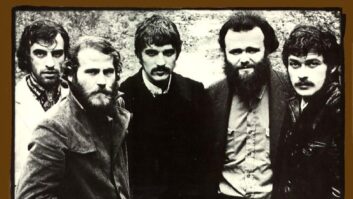

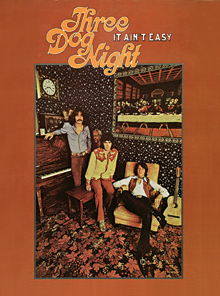

“Mama Told Me Not to Come” — from the 1970 ABC/Dunhill It Ain’t Easy LP — begins with a post-boogie-woogie piano figure played by keyboardist Jimmy Greenspoon on a Wurlitzer electric piano that was miked directly into the console by producer Richie Podolor and engineer Bill Cooper. Its shifting meter — highly unusual for a mainstream pop record — immediately establishes the unsettled nature of the song. The powerhouse trio, whose cut-through-a-canyon vocals stamped the Three Dog Night sound, was formed by Wells along with Danny Hutton and Chuck Negron. Hutton says that Wells fought hard for the song.

“I talked to the guys about this,” says Hutton. “I don’t remember when I first heard ‘Mama,’ but Cory says that he tried to get us to record it for three albums before he was able to wear us down! Randy’s publishing company used to send us a lot of demos, but to tell you the truth, I wasn’t bowled over when I heard the song for the first time. When we fleshed it out in rehearsal, it started to come together, but besides Cory, the rest of us remained lukewarm until we actually got down to tracking it. By the time we’d finished making the record, though, we knew we had something special.”

Podolor says that prior to recording their first album, which was produced by Gabriel Mekler, neither he nor his partner, Bill Cooper, had heard of Three Dog Night. “We cut that initial record [Three Dog Night] in just a few days. It was essentially a live album.” The group’s version of Harry Nilsson’s “One” leapt off the album and put Three Dog Night on the map.

After returning to Podolor’s American Recording Company to cut a second album [Suitable for Framing], Three Dog Night asked him to produce their third album, also cut at American. “One of the most important decisions we made was to sonically treat the four instruments as equals to the voices,” Podolor says today. “It would have been easy — given the hugeness of their sound — to make everything subservient to the vocals, but we thought that would be a mistake.

“The players — [keyboardist] Jimmy Greenspoon, guitarist Mike Allsup, drummer Floyd Sneed and bassist Joe Shermi — are sometimes overlooked. That’s a pity because they contributed mightily to the sound and success of Three Dog Night. We spent a lot of time on the parts. I remember working for about an hour with Floyd on the bass drum part he played on ‘Mama,’ making sure that it kept the track moving.”

Cooper’s memories of the session are vivid. “The interaction of the bass and drums was unique on many Three Dog records, and that was certainly the case with ‘Mama.’ Joe had a Latin influence and he liked to push the down beat slightly. Floyd was one of the slyest drummers I ever heard. He listened to a lot of tribal drum recordings and would incorporate elements of that style into his playing — tom fills starting on an upbeat, for example. Together, they took a groove that could have been ordinary and turned it into something infectious, with a feel that pushed the song forward constantly.”

The character Wells created for “Mama Told Me Not to Come” — a confused but excited party-down initiate, delivering his thoughts in sing-speak with a hard to pinpoint accent — perfectly matched Newman’s ironic lines. Although Podolor and Cooper say that Three Dog Night routinely entered the studio well-rehearsed, they nonetheless recall spending hours recording Wells’ vocal and creating a comp track from multiple performances. “Today, of course, vocal comping is a breeze,” says Cooper. “Back in 1967, Richie was way ahead of the game. On the ‘Mama’ lead, there’s a take change every three or four words.

“Cory talked, or acted, every word of that song. We got maybe three great complete takes from him and then comped them together. Three or four years ago we re-recorded all of Three Dog Night’s hits in the studio using Pro Tools. I looked at waveforms of the guys’ vocal lines and it was very interesting. Most professional singers produce a smooth waveform, but the waveforms from all of the singers in Three Dog Night — Danny and Cory in particular — were fat and fuzzy! That’s why they have that huge sound!”

“The guys didn’t have a classic blend,” says Podolor, “not the kind that you’d want from a choir, or a perfectly blended pop group like The Association. That sound lets you stack harmonies forever. But Cory, Chuck and Danny each have distinct vibratos and different textures to their voices. We had to pay a lot of attention to their use of vibrato in particular and tame it when it became problematic. We had the guys sing together around a single mic whenever we could, particularly on choruses.”

“It gives a much better sound than using separate mics on different tracks,” adds Cooper. “Visuals are important. When the guys are close around a mic, they can see and communicate with each other easily. Phrasing and balance improves naturally, and the guys can mimimize vibrato issues on their own.”

“Let me underscore that point,” Podolor says. “The importance of the visualization element can’t be overstated with regard to Three Dog Night recordings. We cut the band and the singers together, in one room, as if they were onstage, with no headphones. Drummers should never be forced to use headphones unless it’s absolutely necessary. Floyd could hear nuances in his snare sound within the overall timbre of a track. But the moment you put headphones on him — or any other drummer — his dynamic tends to become unvarying and the color of his sound deteriorates.”

Podolor and Cooper used the Scully 8-track recorder they described in an earlier “Classic Track” article (July 2008) on the “Mama” session: “It’s the same one we used when we recorded ‘Born to Be Wild,’” says Podolor. “We’re always ready to modify any piece of equipment to get the sound we’re looking for. But it’s important to know when to leave things alone. Jimmy had an old Wurlitzer electric piano. Most Wurlitzers sounded like the one Ray Charles used — nice and clean. This one had a nasty tone. It was perfect for the character of ‘Mama,’ so we didn’t touch it. We just directed its mono output right onto a track, adding maybe a touch of EQ on the way in.”

Mike Allsup’s violin-like guitar lines add an important texture to the record. “Mike played a Les Paul,” says Podolor. “We tried Strats and other popular guitars, but the Les Paul give the biggest finished sound to his playing. At the time, the group was endorsed by Bruce, a company that made big, solid-state amplifiers. Mike went through a Bruce and a Fender Blender, which was a combo device that had fuzz and other effects. Next to it was a scaled-down revolving Leslie speaker. We’d ‘Y’ the output of Mike’s guitar and record him direct, and through the effects as well. That was his signature sound, the one he always used, unless he was playing a rhythm part.”

“Those records were a true collaborative effort,” says Hutton. “We were all looking for places to introduce different sounds. Mike’s weepy guitar part added a lot, of course. I added a little whistling part with my hands in the middle. At the start of the third verse we recorded an extra bass part using the pedals on the studio’s B3. A friend of mine from grammar school was at the session, and he and I double-tracked the choruses twice, changing positions the second time to help fatten the sound.”

“When we were just about through laying down tracks, we felt that we needed something special on the ride-out,” says Podolor. “Bill handed out individual mics to the singers and they went out in the room and ad-libbed their closing lines.”

Over the course of about five years, Three Dog Night was, by the numbers, the most popular band in America. The group wracked up 21 consecutive Top 40 hits, 12 straight Gold LPs and a whopping total of almost 50 million records sold. However, Hutton is less pleased with Three Dog Night’s place in the pop-music pantheon. “We’ve never been given much credit for anything!” he says with a laugh. “The critics certainly didn’t like us. We were on the cover of Rolling Stone once, standing in front of our jet plane. At that point, we had more hits than Creedence, more Gold than the Stones and took in larger purses than Elvis, but the only angle that the article explored was how huge a money-making machine we’d become. Nothing about how we made records. But we were involved in everything — working with Richie and Bill to create effects we’d never heard before, like the pre-Frampton creation of a vocoder effect, running a vocal through a Leslie to make it shimmer, Mike’s creative guitar sounds. In the age of the singer/songwriter, I think the fact that we didn’t write our own material worked against us. What critics failed to appreciate was our ability to take songs other people wrote and arrange them in ways that were fresh and ear-catching.”

Critics be damned, Three Dog Night continues to play 85 shows a year to enthusiastic audiences. Their catalog has secured them a place in the firmament. And Hutton, Podolor and Cooper are currently working on a round of new material.