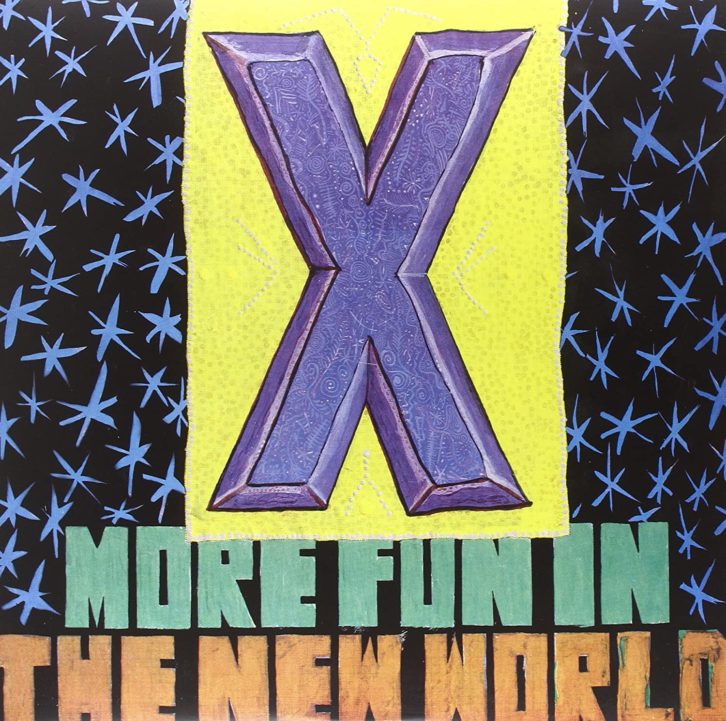

This month’s Classic Tracks story started with an election-week earworm. “The New World”—a single from L.A. punk band X’s 1983 album More Fun in the New World—paints a picture of the America that the band’s principal songwriters, John Doe and Exene Cervenka, observed as X toured the U.S. behind their record Under the Big Black Sun in 1982.

“We were in a different city every night for six weeks, and we saw all of the United States,” reflects drummer D.J. Bonebrake. “We could see the disillusionment of people who were losing jobs. We were in Baltimore and in Michigan. These places were depressed because industries were disappearing. During the Reagan era, the stock market was booming but blue-collar jobs were disappearing. We’d see homeless people. We’d see people begging.”

“Honest to goodness, the bars weren’t open this morning

They must have been voting for the President or something

Do you have a quarter?

I said yes because I did

Honest to goodness, the tears have been falling all over the country’s face.”

Nights at the Office

In preparation to record what would be their fourth full-length album, the members of X—Doe, Cervenka, Bonebrake and guitarist Billy Zoom—began working up arrangements for a new collection of songs in their rehearsal space on Hollywood Boulevard.

“When we signed with Slash, they helped us get that rehearsal space in downtown Hollywood,” recalls Bonebrake. It wasn’t ideal because it was in an office space, so you couldn’t play until 6 o’clock. Also, there was a meditation group down the hall and they would knock on the door and say, ‘We’re going to meditate for a half hour. Can you take a break?’”

Band arrangements usually started with Doe’s bass parts; as one of the songwriters, he would play and sing for the group, and Bonebrake and Zoom would develop their parts from there.

“It’s never just one person, though, and sometimes Exene doesn’t get credit where it’s due,” Bonebrake says. “She’s really good at making suggestions. But in this case, I think Billy came up with the lead guitar part.”

Zoom’s riffs and solos often echo bits of Americana, whether it’s early rock ‘n’ roll or—as is the case in “The New World”—a little like cowboy music. Bonebrake points out that his drum part evokes classic American music, too.

“There’s kind of a martial-sounding part, when they sing, ‘It was better before before they voted for what’s-his-name,’” he says. “It could almost be a John Philip Sousa march. There’s a hint of that.”

Bonebrake also recalls that his drum part on the song posed some challenges. “I’m pretty sure the song was always in 12/8 time,” he says. “But the thing about rehearsing with X is, we rehearse relatively quietly—not a whisper, but, because we were in an office space and we didn’t even have a great sound system in there, we played lighter.

“The beat I do on that song is all eighth-notes and it’s fast on the hi-hat, but when we started to really play it, I realized that may have been a mistake because it’s really hard to play that way and play loud. But I decided it doesn’t sound right any other way, so that’s the way I’ll always play it.”

Remembering Ray

Partway through rehearsals for the album sessions, the band was joined in their rehearsal space by their producer, Ray Manzarek. The former Doors keyboardist produced the first three X albums, and More Fun in the New World would be his fourth and last time in the studio with them.

“We met Ray in 1979 at the Whisky a Go Go,” Bonebrake says. “We were opening a show and Ray was there with his wife, Dorothy, to see the headliner. At that time we were playing a really fast version of ‘Soul Kitchen’ by the Doors. When we started playing ‘Soul Kitchen,’ Dorothy recognized it and she looked over at Ray, like, ‘Hey, do you hear that?’ Apparently he had a blank look; he didn’t recognize it at first. But they came backstage and he said, ‘I really like your stuff—the poetry and the music, and your sound. I’d love to produce you if I could.’”

On Los Angeles, the band’s debut, Manzarek played keyboards on a few songs, but on subsequent albums he served solely as producer.

“At that time in the punk scene, people would say you sold out if you put out a record or signed with a major label,” Bonebrake says. “But Ray always encouraged us and he would remind us that it’s a business. He would make suggestions that made things better, but he never tried to change our sound. He would try to get us in the mood to perform well, give us pep talks.

“He was well aware of what it was like to be a musician, and he knew what it was like to be the oddball. We were part of the punk scene, but we weren’t exactly punk. The Doors were like that, too. They came out of the ‘60s, but they would do a Kurt Weill song, or some poetry. Even though they had hits like ‘Light My Fire,’ I remember listening to their records as a kid and going, ‘Wow, this is dark and wonderful.’ So there was that commonality.”

The Sessions at Cherokee

After the band fine-tuned their arrangements with Manzarek, they all headed to Cherokee Studios to begin tracking in Studio 1. The live recording sessions—with Bonebrake and Zoom in the big room, and Doe and Cervenka in iso booths—were engineered by the band’s live mixer, Clay Rose, who was assisted by Cherokee staffer Brian Scheuble. Mix was unable to track down Rose for this story, but Scheuble offers a unique perspective on the sessions, as this was literally the first studio session he ever worked on.

“Before that, I had been a runner for four to six months,” Scheuble says. “I was thrown into that session and I really was pretty green, but they were the coolest, nicest people and everybody was supportive. I don’t think they ever knew that this was my first session.”

The band played live with Doe and Cervenka singing guide vocals. Bonebrake’s drums were set up in the middle of the room. Though Zoom played his Gretsch Silver Jet guitar in the live room as well, his amp—a 1960 Fender Concert—was isolated. Scheuble recalls that Rose’s experience as a live engineer informed the microphone choices.

“There were a lot of 57s,” Scheuble says. “They were on the drum kit, the guitar amps, the snare, the tom-toms. But there was also a pair of Neumann U87s being used as room mics, and John and Exene sang into U67s.”

Songs were captured to one of the studio’s MCI JH24 tape machines via the mic pre’s in one of Cherokee’s four Trident A-Range consoles.

“It was a well-equipped studio, and we also used 1176s and LA2As and Fairchilds—pretty much all the great old gear that everybody drools over today. I also remember Clay using an old Eventide delay for guitars and vocals, which was pretty standard back in those days.”

“We would do about two songs a day,” Bonebrake recalls. “I think the basic tracking took five or six days, after the first day, which was just getting sounds. We would get there every day and work on a song, and if we didn’t get it we would have dinner and then we’d probably get it on the first take after dinner. Then we’d work on the second song, and if we didn’t get it, we would come in fresh in the morning and get that on the first or second take.

“That’s one of the consistent things about X: If we’re not getting the groove on a song, we don’t beat it to death. We take a break. We’ll come back tomorrow. We’ll make suggestions, but we don’t get microscopic. We let it happen organically until it starts to work.”

When the basics were complete, the project moved to Studio 3 to overdub any replacement parts, solos and final vocals.

“John and Exene would sing together on separate mics with a gobo between them,” Scheuble recalls. “There was never too much analyzing or overthinking on this album. The vibe was pretty light and fun.

“From there, we went right into mixing,” the engineer continues. “Everything was mixed to an Ampex ATR 102 quarter-inch machine. We had no automation; everything was by hand, which was awesome for me because they had me doing moves and I was able to learn how to use the A-Range console very quickly. Everybody had their little part of the board. Ray was down on the far left, Clay was in the middle, John had a couple of faders, and I was on the far right doing some on-and-off for the backgrounds and some percussion. I also remember we used Cherokee’s EMT 140 plates on vocals. It was an amazing trial-by-fire experience, and the first of many sessions I worked on as an assistant and as an engineer for the next six years.”

While he was on staff at Cherokee, Scheuble went on to engineer records by Pat Benatar, the Divinyls, Tina Turner, Rod Stewart and more. He later joined A&M Studios, where he engineered productions by Jimmy Iovine, Shelly Yakus and others. Ten years after working on More Fun in the New World, he coincidentally ended up serving as one of the engineers on X’s 1993 album Hey Zeus. Today he is an independent engineer and mixer.

X stopped working with Ray Manzarek after New World, and sadly the great Doors keyboardist and producer passed away in 2013. DJ Bonebrake and his bandmates have gone through different incarnations and side projects over the years, including a five-year hiatus, but X survives. The band have been touring in their original lineup on and off since 1998, and 2020 saw the release of Alphabetland, their first studio album in 27 years.

More Fun in the New World went to Number 86 on Billboard’s album chart and remained on the chart for 23 weeks—a notable feat for a punk band at that time. Track one, “The New World,” might as well have been written in 2020.