In the spring of 1986, pretty-sounding pop ruled the airwaves. With Wham, Whitney Houston, Sade and Dream Academy dominating the Billboard charts, you’d be hard-pressed to find a distorted guitar anywhere in the Top 10. Over on MTV, “metal” music was a rotation of camera-friendly bands slithering around in Aqua Net and Spandex, whipping their hair to shout-along anthems about parties and girls.

Meanwhile, a dark fury was raging in the music underground, and it was about to bust wide open. Thrash metal, with its face-melting assault of blistering tempos, heavy themes, chugging riffs and a caustic attitude borrowed from hardcore punk, was the antithesis of glam rock, and it was being eaten up by the disenfranchised youth of America.

The pioneers of thrash—Metallica, Slayer, Anthrax and Megadeth—were carving out a new genre that was spreading like wildfire despite the bands’ steadfast refusal to conform to the music mainstream. Of these acts, Metallica was the behemoth, building a massive cult following of tape-trading fans and blowing away crowds of 80,000, opening shows for Bon Jovi, Ratt and Ozzy. Soon enough, Elektra Records and Q-Prime Management took notice, and everything changed.

Master of Puppets, Metallica’s third album, was released in March 1986 as the band’s major-label debut. Five years into their careers, they were maturing as artists, with all four members—frontman James Hetfield, guitarist Kirk Hammett, bassist Cliff Burton and drummer Lars Ulrich—contributing equally to song material. (This would be the final project with Burton, who was killed in a tour bus accident in Sweden that fall.)

Puppets, which was written in eight weeks over the summer of 1985, saw the band become more refined, more powerful and more in control of its direction, on a record that was more intricate, complex and dynamic—more everything.

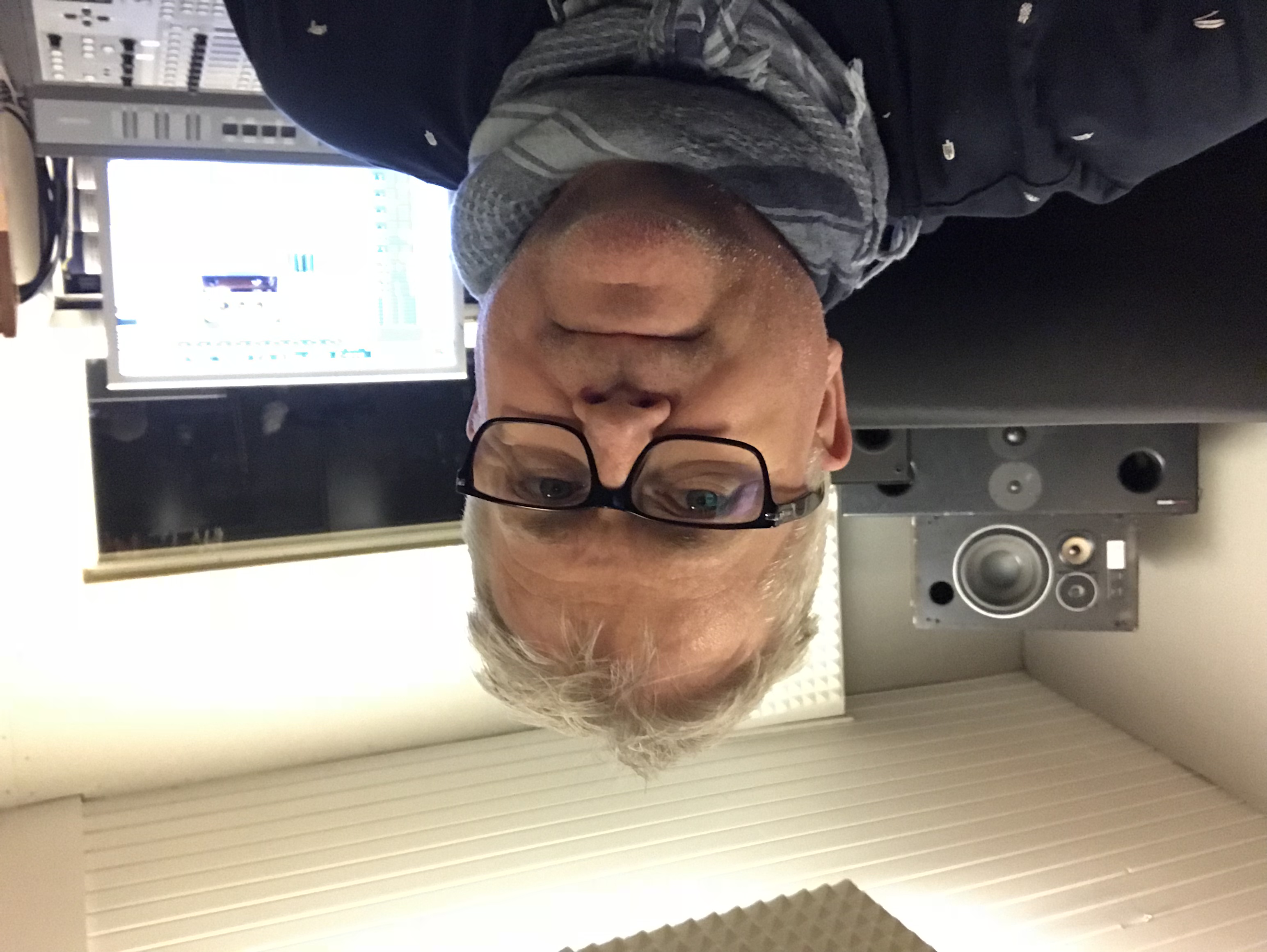

In the fall of 1985, the Bay Area band, then living in Los Angeles, returned to Sweet Silence Studios in faraway Copenhagen to reunite with producer Flemming Rasmussen, whom they had hired on their previous record, Ride the Lightning, after being impressed by his work with Rainbow.

Despite being vehemently “anti-producer” at the time, the band members, who were barely in their 20s and still learning their way around the studio, had an ideal creative partner in Rasmussen. “We wanted to do Ride the Lightning better, louder, more well played, better songs,” Rasmussen says. “Just Ride the Lightning times ten in terms of sound.”

Related: Metallica Mixes It Up: Monsters of Metal Roar in the Round, by Sarah Benzuly, Mix, Jan. 1, 2009

This time, though, the band had a big-label budget and nearly four months to make the record. It was the perfect arrangement: Rasmussen lived five minutes away from the studio, and Q-Prime hired his wife and sister to cook dinner for the band every night. They would eat together, discuss the sessions, then head in to record, breaking just in time to catch the breakfast buffet at their hotel. “In those days, the boys in Metallica called me ‘Dad,’” Rasmussen says. “I’m four or five years older than them, so I was kind of like the father figure in their life.”

Metallica showed up ready to rock, bringing along fully formed demos with fleshed-out arrangements; even their solos were composed. This meant they would use their studio time to focus entirely on their performances—which they did in meticulous, painstaking detail, stopping only for a two-day Christmas break.

The band was honing an aggressive, in-your-face aesthetic, and “no reverb!” was the mantra. “But that meant instead that I recorded a hell of a lot of ambience tracks,” says Rasmussen, who took advantage of cavernous spaces at the studio to capture room sounds.

Rasmussen recorded to tape through the 1976 Trident A Range console that he still works on today. He used the desk’s preamps and EQs, and sent signals through a UREI 1176 compressor to two synched 24-track tape machines. He generally committed to sounds before printing them: “These were all recorded on tape, so the performances you hear are what was played,” says Rasmussen. “My punching-in skills got really fine-tuned on those albums.”

Classic Tracks: Metallica’s “Enter Sandman,”

The album’s title track is a mighty epic, a shot of adrenaline right out of the gate. With its grave themes of drug addiction and control, it became a model for metal’s socially conscious messages. And at more than eight and a half minutes, with complex rhythmic patterns, abrupt tempo changes and three distinct movements—including a long instrumental interlude punctuated by soaring, melodic solos—it feels a lot more like a symphony than a single.

Mostly, though, “Master of Puppets” is about explosive guitar riffs, churning out of and over each other in dense layers. Metallica had just scored an endorsement deal with Mesa Boogie, and it took them a few days to dial in their new guitar sound in the studio. Then, getting that thick, muscular crunch was all about double-tracking—dozens of times over, in mind-boggling detail.

“The rhythm at no point was less than four guitars, and at some points it’s eight guitars,” says Rasmussen, who prefers double-tracking to applying tricks later on. “We’d do James’ sound on his guitar with his amp, and he would double that performance on Kirk’s guitar. We’d do Kirk’s guitar, maybe find a new sound, and would double-track that on James’ guitar.”

Rasmussen often used SM57s as both close mics and room mics, and would place an Aphex studio EQ on a guitar amp’s insert to further fine-tune the sound. He printed verse guitars on one track and chorus and bridge guitars on other tracks. “Then if the B part sounds different, that’s a new batch of four tracks, and then the chorus could be a new batch of four tracks,” he says. “Sometimes on top of that there’s power chords, and sometimes there’s four-part harmonies going on. Everything was written down because otherwise we wouldn’t remember what the hell we had done.”

Interview with Metallica Live Engineers Paul Owen, Big Mick and Mike Gillies

Recording Burton’s bass usually meant capturing one single performance for each song. Burton didn’t like headphones, so Rasmussen would set him up in the vocal booth with a pair of big JBL 4333 speakers. “I’d blast the track through that, and we’d do a DI and the amp, and he would jump around like being at a gig, with the sound blasting from these speakers.”

Burton was an excellent player, but had slight timing issues, so to make sure the band performed their machine-gun guitar riffs in perfect precision, Rasmussen had everyone detune slightly and play to a slowed tape, and then he sped everything back up again.

Sweet Silence had a vast, 45-by-60-foot warehouse in the back; drums were recorded there to take advantage of the huge-sounding ambience. “It was an SM57 on snare top and bottom, AKG D12 on bass drum, one mic on each tom,” says Rasmussen. “I had three mics on the cymbals, and then four to six room mics, including a couple of U87s.”

During Puppets, Hetfield was still honing his signature growl—“He was more or less the angry young man,” says Rasmussen—and production was pretty straightforward: a Shure SM7B, through the Trident desk and UREI compressor, to tape. “We’d do a lead vocal and would double-track it,” says Rasmussen. “We’d work out some backing vocal parts where they decided they should be, but that was about it.”

When recording wrapped, the tapes were sent to Michael Wagener at Amigo Studios in Los Angeles. Wagener had produced records for Dokken, X, Stryper, Poison and Accept that year; he was steeped in metal, yet he heard a new sound in Metallica.

“I’ve worked with a lot of metal bands before, but Metallica was more of a heavy, heavy, heavy metal band,” says Wagener. “They had their very own ideas about where they wanted to go. And it was, at the time, slightly different from what I would normally do, like the reverb-y drum sounds and stuff. They didn’t want all that. They wanted it fairly dry, in your face, and everything loud.”

Wagener received reels of analog tape, which he transferred to digital tape. “We mixed from the digital tape,” he explains. “But we had to line up a bunch of tapes with each other, and it was a fairly extensive recording for the time. But, you know, massive amounts of equipment, and we got a handle on it.”

Wagener mixed the record in two weeks. With much of the band’s signature sound already printed to tape, he focused on creative EQ and delay effects, reaching mostly for AMS and Lexicon delays and UREI 530 and Orban 622B EQs.

Although Wagener occasionally applied an LA4A to tame dynamics, he generally approached compression with a light hand. “I don’t subscribe to the idea of putting compression on guitars because, for me, the guitar amp is the best compressor you can get,” he says. “Vocals, a little bit more, because they’re much more dynamic and they have to sit in that certainly louder space.”

More than three decades later, Master of Puppets has lost none of its sheer power. “They certainly did create a new genre,” says Wagener. “And they’re still in that genre, and that’s why it still sounds modern.” Rasmussen says he’s not surprised that Master of Puppets became an instant classic. “When I heard it, I thought, ‘Wow, this is a good album,’” he says. “I think it was an album that everybody, once we were done, was so proud of. It just felt so good to do it, and it felt right.”

Master of Puppets would not be Metallica’s biggest record, but it opened up a new world for the band. It won mainstream critical acclaim, reaching the Top 30 and selling a half-million copies in its first year despite the band’s refusal to make a music video or release a “radio-friendly” single. It would be the first thrash album to go Platinum, and has sold more than 6 million copies in the U.S. alone.

It wasn’t until Metallica released the self-titled Black Album in 1991 on Elektra that they became one of the top-selling acts in American history, skyrocketing straight to Number One, selling 16 million copies and winning Grammy, MTV and AMA awards.

But Master of Puppets is considered by many to be the band’s greatest achievement, and it is certainly one of thrash metal’s most influential albums. Its legendary title track became the band’s anthem, and it’s still their most-performed song.

Today, it’s easy to take Metallica’s success for granted. But back in 1985, they were just a bunch of 22-year-olds making music they loved, without grander motives. “We were just kids,” Ulrich told Rolling Stone on the 30th anniversary of the release of Master of Puppets. “We were part of a music scene, a movement. At the time, we weren’t aware of the possibilities.”