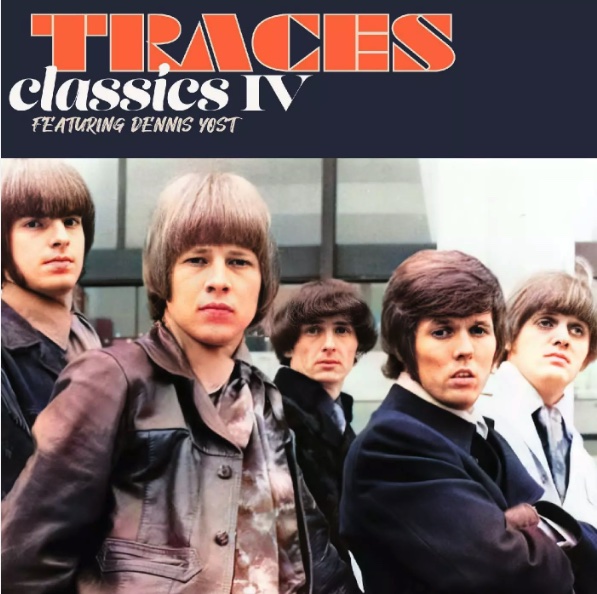

Cover-band mates cum pop stars: As old as rock itself, this dream, born from endless hours spent woodshedding hits of the day, can come true, and in the late 1960s it did for a club band from Florida called the Classics IV. Featuring Dennis Yost’s throaty baritone and a tight rhythm section that comprised the group’s original guitar player, J.R. Cobb, and session players from Atlanta, the Classics IV scored three major hits, “Spooky,” “Stormy” and this month’s “Classic Track”: from 1969, the Number 2 smash “Traces.”

Originally a club band touring the area surrounding Jacksonville, Fla., the Classics IV migrated to Atlanta to take advantage of its greater talent pool. They caught the eye of Joe South, who produced several tracks for them, but South was unavailable for the “Spooky” session, and so Buddy Buie stepped in. “I was a songwriter who would do anything to be around the business before I was able to find success on my own terms,” says Buie. “I was a booking agent for Roy Orbison and Bobby Goldsboro. After Tommy Roe hit the charts with a song I co-wrote called ‘Party Girl,’ I began to get steady work as a writer.

“Paul Cochran, my booking partner at the time, and I went down to Florida to see the Classics IV, and it was clear that they had something special,” he continues. “After they cut ‘Pollyanna’ with Joe South, J.R. Cobb and I started writing together. We were riding down the road one day and heard a jazzy instrumental tune called ‘Spooky.’ We thought we could add lyrics and turn it into a vehicle for the Classics IV. That’s how the string of hits started.”

Emory Gordy Jr., a first-call bass player and arranger, played on all of the Classics IV sessions and co-wrote “Traces.” Buie recalls how the song was written: “We were laying down some other tracks, and during a break Emory went to the piano and kept repeating a phrase that I found extremely catchy. I said, ‘Em, would you care if J.R. and I took that piece and worked on it?’ He said that was fine, and it became the opening phrase of ‘Traces.’”

Cobb, who would leave the Classics IV shortly after “Traces” to concentrate on studio work in Atlanta and spend more time with his growing family, would eventually form the Atlanta Rhythm Section with other session aces, a band that scored its own hits with “Imaginary Lover” and “So Into You.” He recalls the Classics IV days fondly: “We were just a bar band that got lucky and got a record deal! We’d play rock ‘n’ roll in clubs, and the owners would tell us that we had to learn ‘Misty’ or ‘Fly Me to the Moon.’ Those standards worked their way into our playing and writing, and became part of the Classics IV sound.”

“Traces” was recorded and mixed at Master Sound Studios, then one of Atlanta’s busiest facilities. Lou Bradley, who engineered the session, remembers it well. “We recorded a lot of major artists at Master Sound,” he says, “including Roy Orbison, Billy Joe Royal, James Brown and Major Lance.”

The industry was then transitioning from 4- to 8-track technology, and the jump was huge. “We cut ‘Traces’ on a 3-track Ampex recorder that Jeep Harned, who was the head of MCI, had modified into an 8-track,” Bradley remembers. “Harned was a partner in the studio, and the console he built for us was actually the first MCI board. As I recall, it had 12 inputs, two reverb sends and Fairchild equalizers. Jeep later custom-built three EQs into the board, with a midrange that the Fairchilds lacked. As far as outboard gear, we had a Pultec equalizer and an LA-2A. Harned built us a stereo limiter/compressor, and we had a pair of EMT reverbs.”

Dennis Yost, originally the group’s drummer and lead singer, had relinquished his playing duties by the time the group started to record. The late Mike Clark sat behind the kit during the “Traces” session. “I used a 67 on the snare and on the toms and overheads; maybe with a 57 in there, as well,” says Bradley. “I think we put an RE20 on the kick, but I can’t be sure. I know we had an AKG in there, as well, but I’m not sure of the model.

“One thing that stands out in my mind is the amount of time we spent getting Dennis’ lead vocal on tape,” Bradley continues. “Buddy was extremely particular about phrasing. I’ll bet we spent 30 to 40 hours tracking the lead before Buddy was happy. One night, Buddy said, ‘That’s it, we’re done,’ but to me, Dennis was still a little off-pitch on the first two or three notes of his entrance. Today you might use pitch correction, but of course that was not available at the time, so I took a filter and rolled a bunch of the bottom out of the first several notes he sang. Don’t get me wrong — Dennis was a great singer who did a tremendous job on this track. I just helped a tiny bit in this area. I’ve been fortunate enough to work on lots of hit records, and I’ve learned that most of the time they are team efforts, with everybody contributing something to make the product special.”

Yost, who suffered a traumatic injury in 2006 that curtailed what was still a thriving touring career, is remembered as a special talent by Buie. “Dennis had one great voice,” he says, “a voice that filled up the entire spectrum. It was so round, so full. Dennis was hard to record, though, because, believe it or not, he was a James Brown imitator who loved to sing R&B. None of the Classics IV repertoire was in this vein, but I think the passion he had for this music infused his vocals.

“The problem was that he wanted to sing everything hard, and to place the vocal in the context of the material we had to soften him up. During the ‘Traces’ session, I had tell him to take the R&B out over and over again!”

The writers had all been influenced by the music of Jobim and Burt Bacharach, and were particularly impressed by the way Bacharach was able to assimilate a samba influence into his pop songs. Recording Cobb’s lightly inflected nylon-string guitar part, a key element of “Traces,” was not easy. “That gut-string guitar I used was so cheap!” Cobb says with a laugh, “and it played and sounded that way! It was impossible to keep in tune; the nearest I could come to having it stay properly pitched was to use the same voicing for the chords and move that shape up and down the neck. I think the slightly out-of-tune sound of the guitar actually added something to the track.”

And Bradley pulled out a roll of masking tape during the guitar overdub session. “J.R. liked to double-track his parts. He augmented the natural out-of-tune quality of the guitar he was playing by detuning it slightly before we tracked the overdub,” Bradley says. “This was way before Harmonizers were used to get a similar effect, so to highlight what he was trying to accomplish I wrapped masking tape around the capstan of the recorder to change its speed. Then I’d immediately bounce the two guitar tracks together, again coming off of the playback head.”

The recording process that Buie and the Classics IV employed — which started with a basic track laid down with drums, bass and guitar alone, and continued on with multiple overdubs — would later become the norm. Not everyone was working this way at the time. “We spent a lot of time on these productions,” says Buie, “and the arrangements Emory came up with were a huge part of what made ‘Traces’ such a good record.

“The intro, my favorite of all the records I’ve been involved with, took a while to come together,” Buie continues. “Emory brought an English horn player to the session, and that great opening line just kind of evolved. Then there’s that string line that leads into the bridge — I hated it at the time! It sounded so schmaltzy. Now it sounds cool to me. Mixing all of the elements together was difficult, and Lou Bradley did a great job.”

“These days it’s common for an engineer to mix tracks that were recorded at various times,” says Bradley. “The principle is simple: The mixer has to make things sound like they all happened at the same time. Back then I used tape machine delay before the chamber to glue things together. We were still making mono records back then and we had to constantly check both our stereo and mono mixes.

“We had a pair of UREI Time Align monitors, and Altec A7s with a 700 cross-over. These two made a good combination. Once we were all satisfied with the mixes, we shipped them to Liberty Records in L.A. to be mastered.”

They came along at a time when Jimi Hendrix was burning down the universe, The Who were injecting large dramatic structures into the rock vocabulary, and rejecting the forms of the past was the norm for electric bands. The Classics IV offered a kinder, gentler, session-based sound, and their success came as a surprise to its creators. “Me and Buddy would sit around and try to write a standard,” says Cobb, “We were overtly trying to write a ‘legitimate’ song. We had no idea it was going to be a Number 2 hit record — we were astounded! It was a cocktail kind of music; we knew that.”

“That’s right,” Buie adds. “‘Traces’ was the kind of record that today is called ‘easy listening.’ The mid-tempo was a problem, we thought, and we never believed that kids would care about it. But we were wrong!”

The Classics IV enjoyed success with one more single, “Every Day With You Girl,” before disbanding. Never a super-group, their catalog of hits nonetheless ensures them an honored spot in the history of pop rock.

Thanks to Joe Glickman, the “fifth Classics,” for his help with this article. Glickman has shot a documentary on the Classics IV that is currently in post-production. More about the group can be found online at www.classicsiv.com.