It was a trial-and-error process of trying to make Voices ofLife sound pleasant enough to Western ears and to people used tosomewhat more high-fidelity recordings, without removing the realcharacter of the choir.

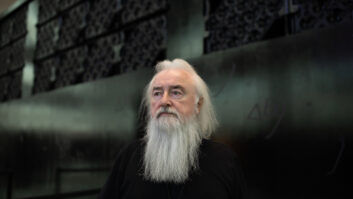

Eddie Jobson is a man with parallel careers — art rockprogenitor, contemporary instrumental forerunner, world musicadventurer and cutting-edge television composer. The giftedmulti-instrumentalist perennially seeks to expand the boundaries ofmusic, unconcerned with the niche marketing mentality that hasseized the record industry over the past decade. “My interestin music, since I was young, has always been in what wasprogressive,” asserts Jobson. “In other words, who wasdoing what was new. I’ve never had that much interest in music thatwas frozen in time.”

Unlike many progressive rockers who strive for a certain sound,Jobson seeks out new and exciting musical possibilities regardlessof genre constraints. A recent trinity of musical works proves this— four seasons scoring the successful CBS series NashBridges; producing and remixing the recent Voices of Lifecompilation for the Bulgarian Women’s Choir; and creating Legacy, aprogressive rock opus. These projects may seem quite disparate onthe surface, but they’re not surprising given the eclectic musicalpath the British musician has forged for himself over the past 25years: He’s appeared on over 50 albums, from his early days withCurved Air and Roxy Music, his progressive adventures with UK andFrank Zappa, his two mid-’80s solo albums (including 1985’sTheme of Secrets, the first album entirely performed and recordedon the Synclavier), on through to his recent work. He’s also wonCLIO awards for Best Score for work on Amtrak and Bermuda tourismcommercials.

Jobson’s most recent high-profile gig was scoring nearly 100episodes of CBS’ Nash Bridges. Star and series executive producerDon Johnson knew Frank Zappa’s music fairly well and thus was awareof Jobson’s musical chops. “It was his directive to do thescore in a world music style,” explains Jobson. “He waspersistent in his request for percussion, percussion and morepercussion, especially African percussion. What became a biggerchallenge was that many of the normal tools you would use forscoring were removed — such as harmony, melody, being able touse synth pads or strings. Any of the typical things that you wouldevoke emotion with in order to capture the sense of the scene wereessentially forbidden.”

The composer relished the challenge, generating an utterlyoriginal palette of sounds. Jobson incorporated acoustic guitar,didgeridoo and quirky instruments such as a harmonica and a Jew’sharp. “It was a great experience, because it made me learn alot about certain types of music, from rap to mariachi, that Iotherwise may not have fully listened to,” he says.“This whole process certainly expanded my understanding ofmusical styles.”

Some episodes were done with specific styles: One episodefeaturing Nash’s MIA brother “started off as Chinese and endsup as Vietnamese in style,” Jobson notes. Other shows hadonly one dominant style, like bagpipes and Irish pennywhistle inthe “Brothers McMillen” episode. Further, Jobsoncomposed nearly all of the background music heard in variouslocations, be it a Chinese restaurant or a shopping mall or alow-rider’s car.

Although he had a music editor, Jobson engineered all of histracks himself. “I played all the instruments. The music wasall programmed on the Synclavier but using external MIDI samplersand synths.” Working on Nash Bridges took up eight months ayear for four years. “Television is a very tough medium for acomposer,” Jobson says. “Everything is done under suchpressure and deadlines. Demands are being made all the time tosound like record tracks, which people spend weeks, months, evenyears on, and yet, as a TV composer, you literally have to turn thetrack around in two or three hours. We did 1,500 pieces of musicfor Nash. I was making 15 cues a week, often with just two or threedays to do it in.”

After the fourth season, which ended in the spring of 2000,Jobson decided to retire from Nash Bridges, because there were twoother projects he needed to finish, both involving the BulgarianWomen’s Choir. He had begun working with them in 1995 for hisLegacy album — which was originally intended to be a UKreunion album but evolved into something bigger — as well asproducing and remixing tracks for a compilation of the choir’smusic.

The pairing of Jobson and the Bulgarian Women’s Choir waskismet. During the choir’s successful U.S. tours between 1987 and1989, Jobson was living on the Caribbean island of Montserrat,absorbing socca and reggae, completely oblivious to their music.But in 1993, friend and former UK bandmate John Wetton played himthe beguiling, otherworldly sounds of the choir, and Jobson wasawestruck. “The level of dissonance and harmonic complexitywas incredible,” the composer recalls. “The fact thatthey could actually sing this was astounding to me. There was justsuch a rich musicality to it and [such] depth and history. Ittapped into something from my childhood.” That connection washis exposure to a myriad of forms of Balkan folk music and Africanmusic through the still-active Billingham International FolkloreFestival, co-founded by Jobson’s father in his hometown in northernEngland.

As a curtain boy at the theater, Jobson was exposed toperformers from Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Ukraine andHungary. “At the time, I was a classical musician but wasexposed to all of this rich, deep folk music — theaccordions, the cymbalom, the gaida, which is a kind of bagpipeinstrument, and double-reeded, Middle Eastern-sounding instruments.All of this was part of my upbringing.” It also tied intoJobson’s love of Russian classical music. “Listening to theBulgarians’ music tapped into early feelings that I had about thismusic of the region.”

The choir’s 2,000-year musical history further tantalized theaccomplished musician. “They have parts of their singing thatare still diaphonic,” marvels Jobson. “This is avestige of early polyphony when Bulgaria was isolated from the restof the world [for 1,000 years], just before polyphonic harmonydeveloped in Western Europe. And the fact that you can still hearthat in their music now — these diaphonic lines or soloistssinging over a single drone — is fascinating.”

Even more compelling for Jobson was the fact that the choir hasspent the last 50 years pursuing innovative ideas. “TheSoviets brought in extraordinary, contemporary classical composerswho have tried to do extremely cutting-edge things with thechoir,” he notes. The Bulgarians’ other collaborations alsoecho Jobson’s own progressive predilections. They have worked withthe Kodo drummers of Japan, the Tuuvan throat singers Huun Huur-Tu,the Moscow Art Trio and a flamenco singer from Spain. Add to thatlist an art rocker with an equally eclectic career. “It showsa good spirit of innovation that they’re prepared to embrace allkinds of music,” he says.

Once he heard them, the mesmerizing sounds of the BulgarianWomen’s Choir ignited Jobson’s imagination. He began formulating aproject that he felt would take progressive music into the nextcentury. He had no desire to relive his days with UK, but he wantedto take what they had done and extrapolate where progressive musicmight have gone in the last two decades — beyond the jazz andclassical influences that were paramount to ’70s prog rockerslike UK, ELP and Yes. Inspired by the global village that moderntechnology was helping to build, Jobson began to look at bringingin music that had escaped the embrace of past progressive rockers— such as blues, funk, and most importantly, world music— as well as to free the style from a stringently structured,nearly academic viewpoint.

“What I came up with was what I now call ‘globemusic,’” remarks Jobson. “The difference betweenglobe music and world music is that world music tends to still bevery ethnic and favors the Third World. Globe music recognizessomewhat more cultured musical styles and tries to incorporate theminto an amalgamation of other somewhat more cultured musicalstyles.”

Integrating the Bulgarian choir into the Legacy project was farmore complex than it sounds. Jobson faced a series of hurdles intaking his own words and making them singable by the choir.“The first challenge was understanding what their music was,where the style originated and learning all these stylisticelements that were combined into this sonic montage that is theBulgarian Women’s Choir.”

The second challenge involved translating his musical ideas intotheir own musical dialect. “Every little yelp and whoop andyodel was very precisely written using fairly archaic notationdevices. There were inverted mordents, turns and other devices thatI hadn’t worked with or seen since studying music theory when I was14 years old. But there it all was in the score. They’re a highlydisciplined choir. Even though they are traditional folk singers,they have a very strict regimen of classical study. They all readmusic extremely well.”

The third challenge was translating Jobson’s poetry intoBulgarian words. He sought the talents of a Balkan poetry professorfrom Boston University, and together they worked out the poems intoBulgarian. “It’s a very percussive language,” explainsJobson. “A lot of the words just don’t seem to have anyvowels in them, so I would ask him what a certain English phrasewas, and he would come back with this machine gun staccato that wascompletely unsingable. Further, he said that some of the lyricsthat they used were not only in Bulgarian, but they were fromarchaic Bulgarian folk poetry. So to really do it in the authenticstyle, we had to use phrases that would be typical of ancientpoetry. I would come up with these phrases, and he would findinteresting metaphors that they would have used a couple ofcenturies ago.”

The last step in scoring the music was writing the words in theproper alphabet. The choir reads in the cyrillic alphabet, soJobson found a transcriber in New York to rewrite the score“because in vocal scoring, every syllable has to have a noteassigned to it. Where you may have one note with a three-syllableword, that one note had to be turned into three notes with theright rhythm. So we had to rewrite the entire score [and integratethe] cyrillic words by hand, which was remarkable towatch.”

The musical and lyrical theme for Legacy was inspired by histrips to Bulgaria to begin recording the choir, to the CzechRepublic to record the City of Prague Philharmonic, and by hisobservations about what had transpired there over the last 50 yearsand the aftermath of Eastern Europe’s despotic regimes.“That’s what the title refers to,” he says, “thelegacy that’s been left not only by the oppressors, but thisspiritual legacy that has been retained by the people, despite somany years of hardship.”

The first recording sessions for Legacy took place in 1995.Jobson recorded the group in the Russian Cultural Center in theBulgarian capital of Sofia, bringing in 14 cases of digitalrecording equipment from Floating Earth, a company that specializesin on-location classical recording. For the 1999 sessions, herented a cathedral and brought equipment and recording engineerMike Cox from Abbey Road Studios. Jobson miked the choir with fourpairs of Schoeps microphones run into a Genex 20-bit hard disksystem. He utilized a Tascam DA-88 for playback. Because the twoLegacy vocal numbers were to be later integrated into rock songs,the conductor required the use of a click track.

The recordings were contained to just eight tracks. “Ididn’t want to get into too many microphones,” Jobsonremarks. “We wanted to keep it fairly pure, so we just had acouple of solo mics down in front of the choir, and then the maintwo fairly widely spread close mics. Then a couple of higheroverheads, and then a couple of ambient mics.” Mixing thetracks was relatively easy: “I usually found that just two ofthe pairs were enough, usually the close mics and one of theambients mixed in was enough, if you had the rightplacement.”

After beginning work on Legacy, Jobson became sidetracked withscoring Nash. Then the Bulgarian Women’s Choir record label inGermany approached him about releasing future albums by the group,especially as Jobson had founded a label for thedifficult-to-market Legacy project called Globe Music Media Arts.He suggested assembling a compilation of their best live and studioperformances, basically a mixture of released and unreleasedmaterial. He would later add three tracks from the Legacy project— “Zavesata Pada (The Curtain Falls),”“Utopia” and the instrumental album intro “NovDen (A New Day)” — but in a form more befitting theirstyle.

For the Voices of Life album, Jobson spent two months in hisL.A. studio remixing the older recordings to clean out noise— “air conditioning buzzes, lighting hums and even alot of coughing from the audience, which was very difficult toremove,” he explains. “A lot of it came down to clevermanual editing on Pro Tools to remove sounds and then trying toextend sounds from other places or even time-expand sounds in orderto fill gaps that we’d taken out; sometimes editing in-betweenphrases and filling the phrases with high-quality digital cathedralreverb. A lot of the work on my part was in trying to make therecordings sound like high-fidelity, full-sonic recordings, whereasmany of the original recordings didn’t. I did that just byextensive EQ’ing.

“The choir’s tonality is very difficult to record,especially when it’s not miked terribly well,” he continues.“You end up with a lot of shrieking formants in the sound,and these can really combine to create this dense, high-pitchedwhistling in the sound that on speakers can be pretty unpleasant.It was a very difficult job, because I had to take very narrow Q’son those harmonics and isolate them and notch them out. But therewere so many of them within the one sound that by the time I gotthrough it all and notched them all out, a lot of the presence ofthe track would disappear. So then I’d have to rebuild it back upagain with a more pleasant top end, bring the presence back inwithout that obnoxious sibilance. It was a trial-and-error processof trying to make it sound pleasant enough to Western ears and topeople used to somewhat more high-fidelity recordings, withoutremoving the real character of the choir.”

Voices of Life, the dynamic Bulgarian Women’s Choir compilationthat also includes guest spots from King Crimson’s Tony Levin (onChapman stick), Bill Bruford (drums), Jobson (electric violin andsurreptitious synths) and the string section of the PraguePhilharmonic, has found a receptive audience in the States; theBulgarian Women’s Choir successfully toured the U.S. last fall.Jobson and the choir made numerous NPR appearances, and CNN tapedone of their performances. In addition, they were selectedInternational Artist of the Year on Amazon.com, and they havereceived critical acclaim from prominent newspapers, including TheNew York Times and the Los Angeles Times.

One hopes that the critical acclaim that the Voices album hasgarnered will also find its way to Legacy once it is finallyreleased. But Jobson is concerned with staying true to himself, nomatter where his muse takes him. “I suppose, when I lookback, it does seem like I’ve gone in a lot of differentdirections,” he observes. “But for me, it’s always beenthe same direction, it’s just been in pursuit of new, interestingthings. I try to stay on the cutting edge as best I can, both withtechnology and with whatever’s going on musically, because that’swhat gets me out of bed in the morning: not getting too stuck onthe same thing and going into a repeat formula mode.”

For more, log on to www.globemusic.com.