For most music aficionados, the word “funk” translates into hip-swaying, booty-shaking rhythms. However, for George Clinton — creator, producer and impresario of Funkadelic, Parliament and the P-Funk All-Stars — funk is a much broader concept and more mystical; it’s an essential component of life. “The funk has no limits or bounds and you can never have too much,” he says. “It can’t be stopped and it will never die.” Spoken like a true believer.

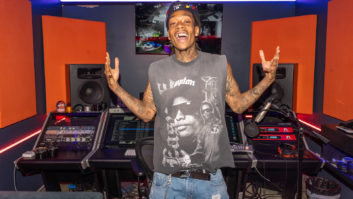

As for the music, Clinton’s hard funk flourishes best in a concert setting: Every show is a Felliniesque party, with his musicians decked out in costumes that range from hilarious to erotic, and his audiences deliriously dance to the nonstop onslaught, swept up in the waves of rhythm, melody and noise that emanate from the huge conglomeration of players who fill every inch of stage. Clinton himself is a walking cacophony of tossed hair, clashing colors and outlandish outfits — adored by both his players and fans.

Most of Clinton’s career has been dedicated to this sort of anarchic funk — yet 50 years ago (can it really be?), he was a founding member of a tame doo-wop group called The Parliaments. By the late ’60s, however, he was already on the path of funk-rock righteousness. In 1968, he formed Funkadelic with keyboardist Bernie Worrell and others as a sort of psychedelic alter ego of the more commercial Sly & The Family Stone. With its Jimi Hendrix — inspired guitar lines and long jams, the band was more an underground cult sensation than a mainstream attraction. By 1972, Clinton had combined elements of his old Parliament group (including bassist Bootsy Collins, who’d been playing with James Brown) and Funkadelic into a series of edgy, horn-driven bands with large and loose memberships that sometimes swelled to dozens of players. A string of hits emanated from different configurations of Clinton’s bands during the ’70s, including “Dr. Funkenstein,” “Chocolate City,” “One Nation Under a Groove,” “P. Funk (Wants to Get Funked Up),” “Tear the Roof Off the Sucker (Give Up the Funk)” and “Flashlight.”

During the ’80s, Clinton’s mighty funk machine was occasionally derailed as a result of personnel squabbles and legal skirmishes with various record labels. Nevertheless, the funkateer scored a major hit with “Atomic Dog” from the 1982 solo album Computer Games. With Funkadelic/Parliament dead in the water, he resurrected his musical collective and formed the P-Funk All-Stars. Now, years later, his genius has been recognized by both rappers and rockers. He has been sampled often and is widely regarded as one of the true fathers of funk. In 1997, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (with Parliament and Funkadelic) and received an NAACP Lifetime Achievement Award.

Clinton’s latest move is forming The C Kunspyruhzy, a new label for which he has recorded his first studio album in more than 10 years, How Late Do U Have 2BB4UR Absent, a double-CD containing 25 songs and jams. Additionally, he won a court order that gave him back control of some of his earlier music, and that will also come out on the new label in due time. “We have about 10 albums waiting in line and some remixes coming, too,” Clinton says. “Each of them has two or three cuts from members in the band, so you’ll be able to hear what each one of them is about. They have different focuses and some will sound like P-Funk songs. But it’s a good representation of where our focus is at.”

How Late… is a typically diverse and idiosyncratic album, featuring scores of players and singers (from Parliament forward), including three generations of his own clan. “‘Never Ending Love’ has about 50 people on it; some of the voices are like a choir,” he notes. “My granddaughter [Sativa] does ‘Something Stank (And I Want Some)’ — that’s very different from what we normally do, but it still sounds like us. Also, my son [Trey Lewd], who’s a good writer and singer, is on ‘Su, Su, Su,’ ‘Our Secret’ and a few other songs.” Clinton also collaborated with funk and R&B luminaries such as Prince, Bobby Womack and Collins. Some of the tracks date back as far as 1994, and parts of an unreleased Funkadelic album also found their way into the eclectic stew. Clinton produced most of the album himself, along with Jazze Pha and Kenny Hamilton.

“I prefer cutting with a live band instead of the Pro Tools stuff that doesn’t have any feeling,” Clinton says. “However, we did most of this CD that way because we worked with a lot of existing tracks. I put [the engineers] through the test to do things they normally wouldn’t do and sometimes asked them to do the impossible, but mainly it was basic stuff.” Continuing, Clinton comments about the rawness of the recording: “We had the organic representation, some EQ and very little sequencing, with a sample of something here and there. But we even made that get funky. It was bad enough to use a drum machine sometimes and then have the drummers overdub percussion. But with most of this stuff, we didn’t have to do too much to it, unless it was on analog tape. But the main thing was to get that analog feel as much as possible. If I do all digital, I’ll sample some Bessie Smith records so I can get some of that cracking sound; they have to get some dirt on the CD.”

Clinton admits to being somewhat out of touch with current technology. He doesn’t have a personal computer and isn’t able to program his cell phone. Just the same, his networks of cohorts are constantly presenting discs, files and other formats to him, and with help, he has learned how to make the most of them. “There are tracks from all over the place, with some already premixed years ago. Sometimes, nobody would know where the separated parts were, so we would put the tracks on tape and overdub them. Most of that stuff I have in storage.” The studios he used during the project included United Sound (Detroit); DARP, Platypus and Atlantic First (Atlanta); Hyde Street (San Francisco); Or What (Tallahassee, Fla.); Sound Castle and Sound & Sound (L.A.); Paisley Park (Minneapolis); and many others, each with its own engineers and assistants. Still, there are two engineers the nomadic and visionary producer relies on more than anyone else: Larry Ferguson, based in Los Angeles, has been an important member of Clinton’s team for more than two decades, while Gary Wright has become a significant factor the past four years.

Ferguson, who’s also a close friend of Clinton’s, describes what it’s like to be around him and work on “the funk”: “George is totally different from anybody else. For example, he may be in Minneapolis or somewhere hanging out with a friend and they come up with a song. He’ll have a copy of the track that he absolutely loves on a DAT and continues traveling around. So he’ll go to a studio wherever he’s at — like Detroit — and record to hard disk while overdubbing. That becomes a master, and he’ll manage the stereo tracks, adding vocals, horns and anything else [through Pro Tools]. Then he’ll leave the file or whatever format he’s working on with me to do whatever I want.

“However, that’s both good and bad, because sometimes he’s married to what he’s done. You can’t change anything on him [too much] because he has an unbelievable memory. As a matter of fact, he never writes lyrics, music or notes down. He’s definitely a special person, but at the same time a regular guy who doesn’t care about material things and really just lives for music.”

For the new Clinton project, Ferguson mixed seven tracks at DARP through an SSL board to Pro Tools over several weeks. Clinton’s preference is for things to not sound too polished. Ferguson says that several times he was in the process of finishing up a track when the producer would yell out, “Make me a copy of that!” Normally, that means don’t do anything else to it, but sometimes it can also mean that Clinton wants to do more to it. Spontaneity is a large part of Clinton’s makeup, on- and offstage.

In Tallahassee at C Kunspyruhzy’s new headquarters, Wright — who has spent time engineering in New York, L.A. and Boston previously — was hired on as a permanent engineer. Besides working on current sessions, his duties include archiving, managing and modifying the enormous amount of material generated during the years by Clinton’s many funky manifestations. “We have hundreds of 2-inch tapes and ADATs, so I either enhance them, do overdubs or make completely new tracks through Pro Tools. For instance, ‘Goodnight Sweetheart, Goodnight’ was an old doo-wop song and I did a trip-hop/jungle version of it. That’s pretty much a lot of what I’m up to — sort of looking to the future of the funk. George is so prolific and probably the hardest-working man I’ve ever met, constantly cranking out 15 to 20 tracks a month. But sometimes things don’t get completed, so I often finish things up for him. He’s a legendary innovator, always has a concept and it doesn’t always become apparent what he’s doing. But the funk is always there.”

Wright, who also did the bulk of his mixing for the new CD at DARP, says the studio tools he uses most often on Clinton’s music include a Fairchild compressor/limiter plug-in and Eventide Harmonizer, various Filter Bank plug-ins and, because he’s a keyboard player, the Access Virus synth plug-in. When not working on projects from Clinton’s vaults, Wright produces other musicians’ projects and creates his own music. However, working with Clinton means that there isn’t much time for outside projects: “George is always on the road doing something, and within the span of a week, he’ll be performing in Houston, in Minneapolis with Prince, in Atlanta with Lil John, then back in Houston with Scarface. So he records stuff on the road and brings it here. [Ultimately,] our goal is to make Tallahassee the next Motown and have his music — new progressive stuff, along with hard funk and dirty Southern hip hop — explode out of here.”