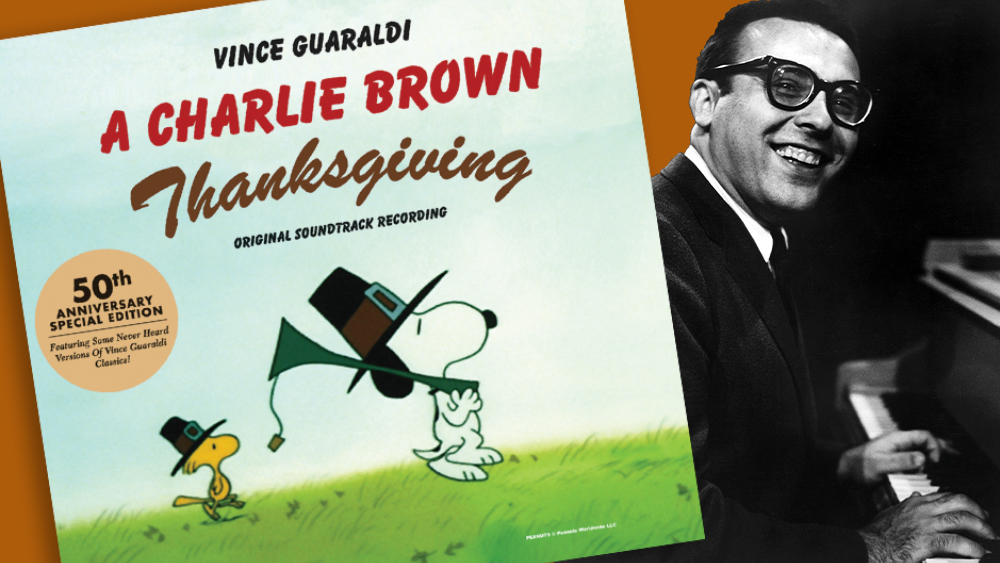

New York, NY (December 1, 2023)—Good grief! It’s taken 50 years for the soundtrack to A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving to reach our ears. Fans can rejoice, however, as this beloved Peanuts/Vince Guaraldi jazz collaboration recently emerged from deep in the vault and found its way into the capable hands of Terry Carleton, who mixed/remixed all the cues and bonus tracks from the original recordings, and Vinson Hudson, who then mastered/remastered those remixes. In addition to the acclaimed composer Guaraldi on keyboards, the recording features Seward McCain on electric bass, Mike Clark on drums, Tom Harrell on trumpet and brass arrangements, and Chuck Bennett on trombone.

Sean and Jason Mendelson, sons of Lee Mendelson, who was the creator and executive producer of the Peanuts TV specials, served as music producers on this project. (Lee Mendelson Film Productions is the publisher of the Vince Guaraldi musical catalog.) The album includes the original recordings that comprise 13 song cues from the television special, plus nine never-before-heard bonus tracks, including Guaraldi singing the lyrics he wrote for “Little Birdie.” There are also several alternate takes, some of which contain snippets of conversation. This record, which Hudson lovingly dubs a “legacy project,” was well worth the wait.

Mix engineer Terry Carleton has known the Mendelson family for nearly 30 years, having worked with the patriarch, Lee, as well as his son Sean. After Lee passed away in late 2019, the brothers began looking through the Peanuts archives and quickly realized that they held a treasure chest of musical gems.

The Charlie Brown music, they found, had been recorded in stereo at San Francisco’s Wally Heider Studios, then mixed in mono for the original television airing on November 20, 1973. The music had never been released as a record.

THE ORIGINAL TAPES

The Mendelsons’ first order of business was to bake the original tapes and convert them, track by track, into “a pile of high-resolution .WAV files,” according to Carleton, who would then bring up all the faders and simply listen to what the players were doing, adding some EQ to brighten certain elements and maybe a touch of room reverb to make it sound more like they were on a stage instead of a small room. “All the elements were there,” he notes, “beautifully played and recorded.”

The bass tones were an exception, however, with plenty of occupied low frequencies but no real sense of performance. Carleton ended up “dumping a bunch of low end and boosting the high-mids,” so you could hear the fingers or the pick hitting the strings. “The sound was ‘flubby’ and different from song to song,” he explains.

“Bless their hearts, they recorded the bass on two tracks—on tracks 1 and 16. Track 1 was the direct sound, direct into the mixer, and track 16 was the bass amp mic. In almost every case, I used the direct sound because the mic sound wasn’t that much better, and it had bleed on it.”

He featured the grand piano more prominently by making the low end a little more boisterous and the high end prettier and shinier. “That kinda gets the piano out of the middle of the mix, because then you hear the high end coming out of the right and the low end coming out of the left, so the midrange comes up the middle,” he says. “By doing that, it allows the bass drum and the bass guitar to sort of dominate in the middle of the mix, so that everyone has their spot.”

The biggest challenge Carleton faced, he says, was how far to go with EQ, compression and reverb: “I didn’t want it to sound bigger than life, like a metal or hip-hop engineer mixed it.

I knew instinctively that we—Sean, Jason and I—wanted to keep the original integrity of the tracks, just enhance what’s there. But how far to enhance? I would ask myself, ‘What would those guys back then have done?’”

Carleton worked out of his Northern California home studio, Bones and Knives, which is roughly the size of a two-car garage and is centered around a vintage 32-channel Allen & Heath analog console and an Alesis HD24 hard drive, which mostly served to play back the .WAV files. “The EQ [on the Allen & Heath] is very musical, and I never felt the need to go out of the mixer for other EQs. The reverb I use is an analog Roland SRV 2000—I find the reverbs so cool. They’re transparent; you don’t hear the bucket brigade. I have some more modern ones, but I keep coming back to the Roland. There are 10 presets, and they all sound great.

“Except for the playback mechanism, everything I used was analog,” he confirms. “I did it just like they would have mixed a Brubeck album, with no automation, no quantizing, no auto-tuning. The project was all mixed analog, with ‘fingers on faders.’”

MASTERING AND REMASTERING

Mastering engineer Vinson Hudson received Carleton’s mix files and loaded them into the all-digital chain at his London Lab Studio, also in Northern California. He didn’t want to create a pop record, he says, and he didn’t want to reproduce it old-school. He wanted to give fans something new, but still familiar, so it would be accepted. His greatest fear was that Peanuts aficionados—a very loyal group of audiophiles— would say, “He ruined it.”

“This was like somebody saying, ‘We’re going to let you re-master Led Zeppelin.’ I’ve worked on major projects, but I’m not really part of that network,” Hudson admits. He decided that he would focus on the fans and what they would want.

What immediately stuck out to Hudson was that Guaraldi played piano in the studio much like he did live, with a heavy touch. “Sometimes when he hits the keys, you can hear the microphones react,” he says. “It all depended on the key of the song, too, because certain frequencies will stick out more depending on the key, and certain frequencies are just ugly if they get recorded too loud.”

Hudson focused most on the stereo image— as left, right and center—and was careful to make sure that it would not be as wide as a pop record, or a more contemporary track. “I wanted it to sound like a very well-recorded live show,” he explains. “I wanted it to sound like it was coming from outside of you. I used mid-side EQs, and I always EQ’d the mid information differently than the side information. A lot of the harshness comes from the mid information.”

Hudson was also continually listening to the original balance and did not want to “re-color” the overall tone, which meant avoiding old-school tubes and transistors. “I use three main Waves plug-ins as one unit,” Hudson explains. ”The first in the chain is the Linear Phase EQ Low band, which I reduce ever so slightly, 47 Hertz, with a V-Slope low-shelf instead of doing any low-frequency cuts. With the other two bands, I’ll again, ever so slightly reduce dirty sounding frequencies like 315 to 375 Hertz, and 516 to 586, using a Bell curve at wider Q. No more than -2.0 dB.

“The next in the chain is the Linear Phase Multiband. Most of the time, this one is only used to control dynamic low frequencies from 128 to 171 Hz. The threshold is set to where I’m only compressing less than -3 dB. It takes a lot of listening and feeling to set the attack and release for each band.

“The last in this EQ chain is the Linear Phase EQ Broadband. This one is six-band and used to correct small imperfections before I actually start mastering. When I say small, I mean gain values of -1.0 or -0.5 dB on each frequency. Again, the low frequency uses low shelf slope and bells. I almost never use highpass or low-pass on these.” When he talks about the small imperfections, he brings up such details as hearing the piano pedal in the mix. He calls the corrections surgical.

He also confesses that his all-digital signal path isn’t entirely accurate: “I used an old Lexicon PCM90 reverb instead of a reverb plugin on this particular project to create a slight hint of space. It’s an old mastering trick, but I decided to use a hardware reverb this time.”

In celebration of its 50th anniversary, the soundtrack to A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving was released on October 20 on CD, vinyl and streaming formats. It is a particular source of pride for the Mendelson brothers.

“Hearing the tapes for the first time made my brother Jason and me feel like Indiana Jones in the Temple of Music,” Sean Mendelson says. “The blood drained from my face as I heard Guaraldi’s voice, and then all of this glorious music that we thought was lost to history. I feel so fortunate to be able to provide this music to his fans because I am a huge fan myself. Now finally releasing it makes me feel such joy and strong connection with my father and Guaraldi’s legacy.”