On August 15, 1965, two weeks before their second Hollywood Bowl appearance, The Beatles put on a show that would mark the beginning of true stadium rock concerts, playing to a record crowd of 55,600 at William A. Shea Stadium in Queens, N.Y. The show opened their second U.S. tour, which would run for a little over two weeks, visiting ten different cities.

Realizing the show would be a milestone event, Beatles manager Brian Epstein and Ed Sullivan’s Sullivan Productions decided to film the concert for posterity for a television special to air that Christmas. A restoration of that film, featuring The Beatles’ concert footage, recently appeared in theaters, accompanying Ron Howard’s documentary, The Beatles: Eight Days a Week—The Touring Years.

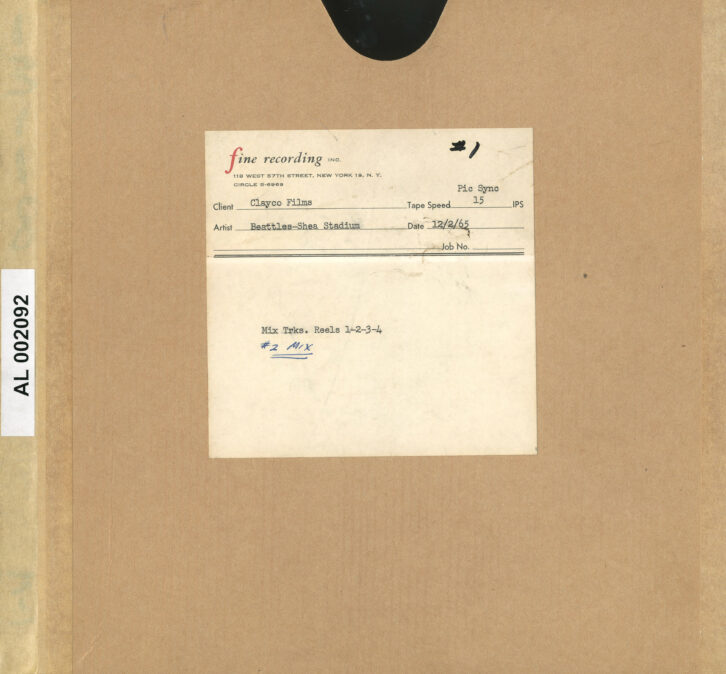

To produce the special, Sullivan hired Clayco Films, whose principal, M. Clay Adams, had a history of work in television, including The Phil Silvers Show, and who would regularly shoot location inserts and segments for Sullivan. The film was shot with a dozen strategically placed 35mm cameras by cinematographer Andrew Laszlo, a family friend of Adams, according to Adams’s son, Michael.

The audio recording was made by a 42-year-old engineer named Fred Bosch. Born in Stuttgart, Germany, Bosch worked as a field engineer for Altec Service Company on theater sound systems, before joining Cinerama in 1951, acting as recordist for all of its three-stripe Cinerama films from 1952 to 1963. He moved with the company to Hollywood in 1960, returning to New York with his family in June 1964, and apparently became a favorite recordist of Adams.

It is unclear who provided P.A. audio engineering services for the show. All promoters on Beatles tours were expected to provide audio for the concerts, as spelled out in their contract riders. For essentially all Beatles concerts, the PA was strictly for vocals – the guitar amps and drums were considered adequate in those days for any audience to hear (something obviously disproven in practice). In Howard’s documentary, George Harrison even jokes about the whopping 100 W amps Vox had provided for that year’s tour!

The P.A. mix was apparently not piped through the stadium’s audio system, as is often described; the vocal mix instead played solely through an array of Electro-Voice LR4 column speakers splayed about the field toward fans. “The delay, combining those field speakers and the screaming house speakers, would have been atrocious; it would have been a horror show,” says legendary live mixer Bill Hanley, who not only mixed the 1966 Beatles Shea show, but three years later, with his brother Terry, would provide the audio for Woodstock.

As it is, notes former Hollywood Bowl engineer Bill Blanton, “The LR4s produced a narrow beam of sound, like a flashlight – that’s why you needed a lot of them.” Column speakers such as these, explains Hollywood Sound System’s Les Harrison, a well-known collector of older microphones, “had virtually no low end and were primarily used for voice only public address systems.”

“It had to have been weird,” adds Blanton, “deafening screams from the fans, and the vocals coming from one place and the guitars from another, in a circular stadium.” And without the screaming fans, Harrison says, “The Beatles would have found it even harder to sing, because the slapback from the curved stadium would have been tremendous.”

As with the Hollywood Bowl concerts, all of The Beatles’ amps and drums were miked for recording, as were the vocals, using AKG/Telefunken D24/D19 microphones, identifiable by their unique side vents that aid in the mic’s directionality. In addition, taped to each of the three vocal mics was an RCA BK6b lavalier, each capped by a jerry-rigged baffle, with foam taped over the screen to limit the effects of wind and increase the mic’s directionality (which was otherwise omnidirectional). Ringo Starr’s vocal mic was suspended on a boom stand, allowing him to swing the mic into place for his solo vocal, “Act Naturally.” In addition, a single E-V 666 appears to be tucked under his crash cymbal on an Atlas MS-20 stand, right next to a D24 set up in front of the kick drum.

In absence of a surviving engineer from the event, it is impossible to determine the exact signal path for the microphones to tape and house – or, for that matter, whether the PA system and mixer were individually contracted by the concert’s promoter, Sid Bernstein, or if, since the two worked in tandem, both the PA mixer and Bosch were part of Clayco’s setup.

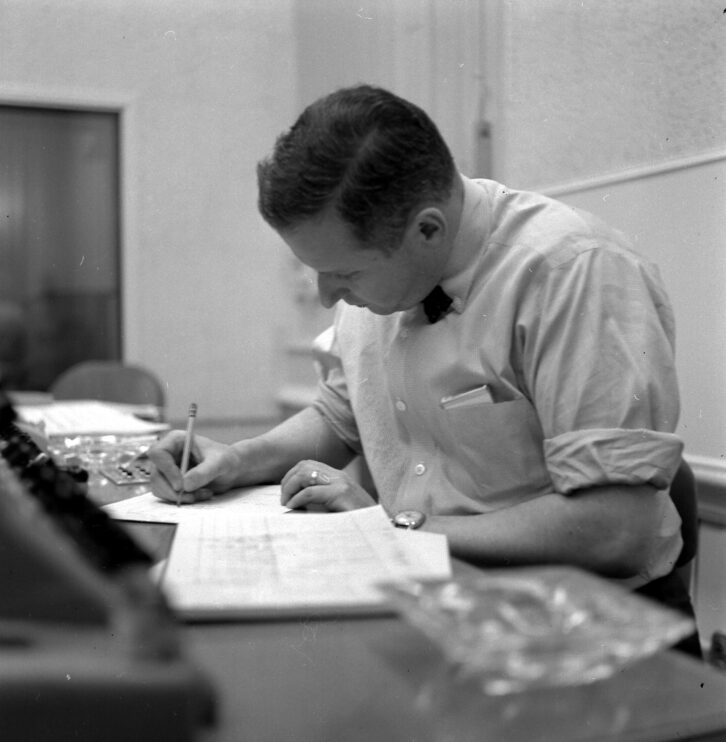

Both Bosch and the unidentified P.A. engineer set up behind the elevated stage platform, just behind Stage Right. Both used Altec 1567A mixers, which had four mic inputs (plus a line input) and a single mono output. “Those mixers were ubiquitous at the time,” says Tom Fine, whose father, film mixer Bob Fine, was the post-production sound engineer for the film. “But they were designed for P.A. and broadcast use. They weren’t designed for a guy screaming rock and roll into a microphone. The overloading could have started at the input transformer.”

Bosch’s two mixers, set up on a cart where he is sitting, are housed in two individual road cases, whose covers can be seen on a shelf below. The PA mixer’s 1567s are housed together in a single road case with two rows of XLR mic inputs on its side. He is only using one of the two mixers (the bottom, the only one of whose VU meter is lit up), and three mic cables are connected in the bottom row of inputs, which are likely the three D24 vocal mics (John’s, Paul/George’s shared, and Ringo’s). [A mic resembling an RCA BK-5, with a “lord mount” and windscreen, is seen atop the case, through which he can address the field, if needed.]

It is not really known which vocal mics are plugged into which mixers, but it is likely that the lavaliers are being used by Bosch, connected to one of his two mixers. And why a lavalier? “They were very popular in the broadcast world, being sturdy, predictable and omnidirectional,” says Harrison. “He probably didn’t have a lot of mics to choose from, particularly one small enough to tape to the D24.”

Study of the raw tapes by James Clarke reveals that the three lavaliers were plugged into one of the Altec mixers, along with the kick drum mic. The two guitar and bass mics were plugged into the other Altec, along with the 666 mic in front of Ringo’s rack tom. As at the Bowl, Lennon’s Vox Continental organ is plugged into his guitar amp, allowing it to be picked up by that amp’s mic.

Bosch recorded the show to Scotch 111 tape on a pair of ¼-inch 2-track Ampex 350 tape machines. Each machine received the same content—the output of each of the two Altec mixers going to Tracks 1 and 2 of each machines, respectively, via an unknown splitter arrangement (perhaps a simple Y connector).

According to James Clarke, the raw tapes reveal Track 1 of the tape contains the mix of the three vocal mics, which are also picking up (as leakage) some guitar/bass amp (most prominently George’s amp, which was directly in line with his and Paul’s mic). The fourth input on that mixer apparently had the kick drum mic, as well. Ringo’s drums are also being picked up by his vocal mic, which, placed on a boom stand, ended up functioning as an overhead. Track 2 contains just the guitar and bass amp mics, along with the E-V 666 drum mic. The guitars are unfortunately heavily overmodulated, distorted throughout the recording.

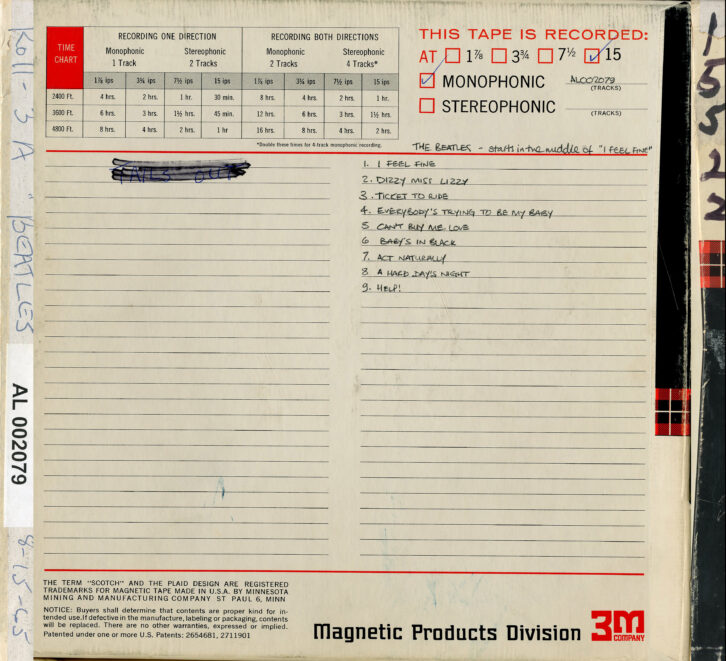

A staggered crossover/backup arrangement was used, similar to what Capitol utilized at The Hollywood Bowl. The “B” machine began the Beatles’ portion of the show at Ed Sullivan’s introduction, recording part way through “A Hard Day’s Night” (the third to last song) before a reel change (losing about 45 seconds), while the “A” machine began at the third song, “I Feel Fine” and ran through the end of the concert. [The entire concert was actually recorded on four reels, the first two containing the warmup acts, with the third and fourth reserved solely for The Beatles.]

Bosch would slate each reel (onto Track 1 only), adding a 1000 Hz tone from an Eico Test Tone Generator, seen under the stage, just to the right of the Ampex 350 electronics.

In addition to the two 2-track machines, Bosch also had a third machine, recording in mono, collecting audience sounds from a mic/mics Clarke believes were placed far from the stage, near the crowd, for use in the final TV mix for the otherwise-dry (crowdless) music/vocal tracks. The electronics for that machine appear to be that which sits atop Bosch’s cart, through which he is seen monitoring the signal with a pair of headphones.

Interestingly, Ron Furmanek, archivist for The Beatles’ Apple Corps in the late 1980s and early 90s, who restored The Beatles at Shea Stadium in 1991 for the company, has a distinct recollection of retrieving all of the raw audio tapes from Clay Adams’s Sea Girt, NJ home in 1987 – including pairs of ¼” 2-track reels, representing four discrete tracks. “[Abbey Road Engineer] Mike Jarratt and I spent many hours,” along with assistant Chris Ludwinski, “syncing those reels up, giving us four tracks from which I could create stereo mixes,” Furmanek recalls.

However, only the pairs of 2-track crossover reels mentioned, containing identical (but staggered) content, exist today in Apple’s archive. It’s possible that Furmanek and Jarrett synced those 2-track pairs though this cannot be verified in absence of the reels he describes (or the synced dub tape).

FIX IT IN POST?

Bosch certainly had his work cut out for him. He was treading in new territory, and, unfortunately, the results reflected it. “Everything was really primitive then,” Fine notes. “You can’t look at this from a modern perspective. These guys had small space and limited time. They just set up whatever worked. This was the beginning of stadium rock P.A.—it had never been done before.” Adds Abbey Road engineer Sam Okell, who restored the tracks with producer Giles Martin, “He’s in the middle of a baseball field, with headphones on and he can’t hear anything. It’s absolutely crazy they got anything.”

The Beatles went onstage at 9:02 p.m. and were finished by 9:36 p.m., performing a dozen songs. The opening tracks, “Twist and Shout” and “She’s a Woman,” suffered from barely audible lead vocals, and vocals are otherwise distorted in many places throughout. For Ringo’s number, “Act Naturally,” Bosch, curiously, somehow momentarily connected only Ringo’s overhead vocal mic directly to the Track 1 input of the “A” machine, leaving just McCartney’s harmony vocal on Track 1 on the “B” machine’s reel for the song—the only place the two reels differ.

Clay Adams, upon reviewing the tracks, turned to his old friend, Bob Fine, for help. Fine, who had a strong reputation in the audio world, both for working on Hazard “Buzz” Reeves’s team that developed the 7-track sound system for Cinerama (and was thus a colleague of Bosch’s), as well as highly-regarded Mercury Living Presence classical and numerous pop and jazz recordings for Mercury, Verve, Command and others. Five years later, he would handle the multi-channel sound mix for another legendary concert of George Harrison’s – The Concert for Bangladesh.

Fine was highly regarded in New York for his film and television post work. His Fine Recording studio was set up in the former Hotel Great Northern, at 118 W 57th Street, where he built a pair of film mixing studios on the building’s 8th floor, connected to the hotel’s former ballroom, which he used for scoring, via audio tielines and a telecine projection system connection with the film mixing studios.

“My father always described to me that the setup on the field and the equipment used was not up to making a recording that was usable for television,” Tom Fine recalls. “He always told the story that Clay Adams came in to do the final sound for picture, and said, ‘Listen, I want you to see if you can do anything with this sound.’”

Fine took three passes at the mix, the first on October 28, after transferring the 2-track recordings to full-coat 35mm mag tape, as was customary for mix for picture work, mixing through his modified Gates Dualux console, which featured a 3-track output. As early as September 23, “She’s a Woman” and “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby” had already been dropped from the TV show’s edit, the former due to an unfortunate absence of footage resulting from camera reel changes, and the latter just due to show length.

His second mix took place on December 2. But upon review a few weeks later by The Beatles and their producer, George Martin, it was determined that the tracks were still not ready for prime time. So a day was booked at London’s CTS (Cine Tele Sound) Studios in London on January 5 for Adams and Fine to record fixes with The Beatles.

As chronicled in a letter from Adams to his son, Michael (featured in Dave Schwensen’s book, The Beatles at Shea Stadium), Adams went to Abbey Road the day before to listen to the tracks with Martin and map out a battle plan, reviewing with Fine that evening. The next day’s session first captured McCartney, who arrived before the others, adding a bass overdub to four songs, and, upon arrival of the others, three songs were re-recorded in their entirety —“Ticket to Ride,” “I Feel Fine” and “Help!” [A redo of “Help!” was required due to long dropouts mid-song on both reels on Track 1, because Bosch had inexplicably disconnected the vocal mix before the song began and connected a mix of both channels, overloading the recording on that track. Mid-song, he switched that same setup to the “B” machine, whose Track 1 remains distorted until the end of the song, while the “A” machine got its proper vocal-only mix back.]

Time ran out, so instead of recording a new version of “Act Naturally,” Martin simply provided Fine with a mix of the studio recording of the song. For “Twist and Shout,” Fine was given the August 30, 1965, Hollywood Bowl recording to replace the Shea recording. The same couldn’t be done for “Act Naturally” – Ringo sang “I Wanna Be Your Man” at the Bowl, thus requiring the studio version.

The Beatles recorded, as would typically be the case at CTS, a popular post-production house, to 35mm full coat 3-track mag, one track of which Fine would have loaded his December 2 mix, the Beatles recording vocals and instrumentation onto the remaining two. “My dad said he was amazed by The Beatles’ ability to sync precisely to picture, particularly when they were patching their vocals. They could match completely what they did onstage,” Fine says.

Upon returning to the States, Fine went back to his studio on January 25 and mixed the 3-track full coat from CTS to a mono mix (sometimes combining the new recordings with the original), and adding effects and dialog, where needed. The finished film was broadcast first in Britain by the BBC a few months later, on March 1, but not until January 1, 1967 in the U.S. by ABC.

RESTORATION

When Ron Furmanek began his restoration research in 1987, retrieving existing audio reels from Clay Adams, what he found, he says, was the pairs of 2-track ¼-inch field recordings, as well as Bob Fine’s three ¼-inch mono mixes (which Fine copied from the 35mm mag finals). “The only thing I was disappointed about was that he did not have any of the 35mm 3-track mag recordings made at CTS,” he recalls. “That’s what I was hoping to find, so that we would have some separations for those overdubs to work with.”

Furmanek says he created true stereo mixes, when possible. For those songs that The Beatles had re-recorded in their entirety at CTS, Furmanek followed suit and used those mono mixes, he and Mike Jarratt buffeting them by creating fake stereo, to avoid sudden jumps when meeting his adjoining stereo mixes. “Twist” once again was the August 30 Bowl recording. “I just couldn’t get a good mix out of the Shea tracks for that; it was a sonic nightmare.”

The original television special included not only footage of The Beatles’ concert, but also other acts on the bill, backstage sequences, etc. But in 2016, an edit of the film featuring just the Beatles footage was restored and released, playing theatrically-only as a bonus to Eight Days a Week. The edit features the entire concert, minus “She’s a Woman” (which, as mentioned before, no footage ended up being captured) and “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby,” whose footage was scrapped following the original edit in 1965.

For the audio, producer Giles Martin and engineer Sam Okell opted to base their restoration work as much as possible on the original raw Shea recordings made by Bosch, rather than the final broadcast mix featuring the CTS overdubs and Hollywood Bowl material. “Sam and I had a rule for ourselves,” Martin states, “and that was, ‘Whatever is live, we must use.’ If they were playing live, and we could hear them playing live, we used it. The whole idea with Shea was about capturing the live performance.”

The Beatles Live! How the Legendary Hollywood Bowl Shows Were Recorded — and Revived Decades Later

“They’re a few sleight-of-hand things that are hopefully not obvious to anyone, but just present the music in a slightly better light,” Okell says.

While the final monophonic soundtrack mixes containing the abovementioned overdubs (and in particular the three songs re-recorded in their entirety, they were not used here, the engineer notes. “They’ve got existing recordings sitting underneath. ‘I Feel Fine’ sounds incredibly phasey. It’s like you’re hearing two things going on at the same time. So we went back to the original tapes and did what we could, even though vocal levels are often low.”

The two worked, for the most part, from Bosch’s original 2-track recordings made on the Ampex 350s, though both Fine’s pre-CTS mixes and his final, which includes them, were also available [only in one instance did they rely on one of the mono sources – Fine’s 10/28/65 mix for “Help!,” for which Fine had skillfully assembled a “comp” of a clean Track 1 from the “A” and “B” reels]

Where fixes were required, Martin and Okell took advantage of other Beatles resources that were available to them from Beatles session tapes of the same songs from the Abbey Road tape library, flying in instruments or vocals which otherwise were wholly absent on the raw recordings.

For “Twist and Shout” and “She’s a Woman,” the first two songs, Okell notes, “The vocals are very low, and they’re blended in with the drums; there’s not much we could do about that, besides EQ and trying to dig that out. So we used a bit of the Hollywood Bowl vocals [from August 30, 1965], in order to bring John up, plus a bit of the rhythm track, where needed. It’s not a total replace, like they did in the film originally; it’s a blend of the two.”

“She’s a Woman” didn’t represent the best performance, so, over the closing credits, the Bowl recording is used.

Similarly, in the absence of a Bowl recording to help it (he sang “Boys” there), Ringo’s “Act Naturally” has some of the studio version, recorded just a few months before, to fill it out. “It was pretty bad,” says Martin. Working from a mono mix reel containing just Track 1 off the “A” reel, featuring only Ringo’s vocal and drum overhead, “You couldn’t hear much of the instrumentation. We had to do a lot of work on that.” The two took the live performance on the 2-track and synced it with the studio multitrack, allowing the addition of the completely-absent guitar, bass and background vocals. “That is the process we had to go through, for the simple reason that we really had no choice,” Martin states. “The original was so flawed, the recording so bad, that we had to combine the two together.”

Other studio help came not only in tracks like, “Dizzy Miss Lizzy,” which was devoid of any low end, but on concert “soundboard” tapes heard in Eight Days a Week itself. Those recordings often surfaced after Beatles concerts, quietly recorded on-site by radio stations, typically without permission, according to historian Chuck Gunderson, whose Some Fun Tonight chronicles all of The Beatles tours. “I interviewed some deejays, who told me they put those on the air for fans, sometimes just a few hours after the show,” he explains. Adds fellow Beatles historian Jim Berkenstadt, “They’re in mono, and you’re typically hearing just vocals, since they’re from a tap off the PA. The only drums or guitars you hear on them is through leakage into the vocal mics.”

Once again, studio sources for those tracks were seamlessly synced up and added into the mix by Okell. “If we had access to a studio rhythm track, for a couple of numbers, we tried syncing that up and then bring in the low end, maybe the bass and kick drum that wasn’t really present on those kinds of live recordings,” Okell notes, “and we were very careful about it; it’s done very subtly. Nobody would know there’s anything else there—it just makes it sound a bit more full than it would otherwise.”

The film and its restored soundtrack, along with the live performances heard in Eight Days a Week, show a hard-playing band, working nonstop to give the fans what they came for—hearing them play, whether they could hear them or not. “They were such a good live band,” says Martin, “and they were the most successful live band in the world, for quite a period of time. People don’t realize that. Hopefully, they will now, after seeing these two films.”