The Beatles were always known for their songwriting and studio wizardry, as evidenced by their 13 iconic studio albums and countless hit singles, but almost forgotten is the fact that, from 1963 to 1966, they were also the world’s most successful rock ’n’ roll live act. With the arrival of Beatlemania in America in 1964, their audiences grew exponentially, essentially forcing them to become the architects of stadium rock tours.

That touring life was recently documented by Ron Howard in his award-winning film The Beatles: Eight Days a Week—The Touring Years. The film, accompanied by a remixed edition of The Beatles at The Hollywood Bowl (originally released on vinyl LP in 1977 and long out of print) and the theatrical-only re-release of The Beatles at Shea Stadium TV special from 1966, offer evidence of the Fabs’ prowess—and raw excitement—as a live band.

Bowl and Shea are the only two multitrack recordings made of the group live. The remaining audio recordings seen in the film represent occasional TV appearances and soundboard recordings, the latter typically made without authorization from The Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein.

The Beatles’ very first concert appearance in the States took place at the Washington Coliseum on February 11, 1964, two days after their record-breaking appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. The show, presented by L.A.-based Concerts, Inc., the booking arm of National General Cinema Corp., was recorded on 2-inch videotape, clips of which are seen in the film. “The idea of us filming it was that we were going to show it on closed-circuit television in over 100 movie theaters three weeks later,” states the show’s promoter, Lou Robin. The broadcast was filled out by segments featuring The Beach Boys and Lesley Gore, transmitted live from a studio in Burbank.

National General shot the show using local CBS mobile facilities, directed by Lee Tannen and technical director Clair McCoy. As seen in the footage, the audio recording was made up of vocals (captured with Altec 633A mics), which were shared with the house P.A., as well as direct feed from The Beatles’ guitar amps to the mobile unit’s recording mixer. It was considered, for the house, as was the case for essentially all of the group’s live performances, that their guitar amps and drums were loud enough for a quiet, polite audience – something the band never experienced. (Starr’s drums, in fact, were picked up, for this recording, only by leakage into the vocal mics).

Capitol Records intended to record the group’s shows at Carnegie Hall in New York the next day, but Musicians Union issues prevented these from taking place.

When the group returned to the U.S. later that year for their first true American tour, they were represented by General Artists Corp., as would be the case for all three years of Beatles tours. GAC invited Concerts Inc. to produce a show at The Hollywood Bowl, but the company turned it down. “They wanted $25,000 and wanted the tickets to go on sale [for the August show] in March, and we normally went on sale three weeks in front, so we passed,” says Robin. “A lot of the English groups that came in weren’t doing business. It wasn’t a slam dunk, when one would come every six weeks.”

KRLA-AM disc jockey (and future Newlywed Game host) Bob Eubanks and his business partner, Mickey Brown, were willing to take the chance, mortgaging a property they owned together in Hidden Hills to raise the $25,000 deposit. Eubanks would continue to bring the band to L.A. over the following two years—again to the Bowl in 1965 and to the larger Dodger Stadium in 1966. “I’m the only living person to have produced their concerts all three years they toured,” Eubanks says.

GAC’s agreement with Eubanks, as with all the Beatles promoters, required (besides a case of soda, a television and towels) “a high-fidelity sound system with adequate number of speakers” and “a first-class sound engineer.” At all venues over the three touring years, sound reinforcement was provided strictly for vocals, and usually included provision of P.A. and loudspeakers, avoiding use of house systems.

Such was not the case, however, at the Bowl, which regularly hosted concerts of all kinds and had its own superior audio system to project to the back of the 18,500 seat (550-foot throw) of the venue.

Though a state-of-the-art RCA-based P.A. system update had been installed in 1955, it was upgraded after the 1960 season with the arrival of Head Audio Engineer Bill Blanton, formerly Ray Coniff’s tour and television mixer at The Coconut Grove, and a team of four techs.

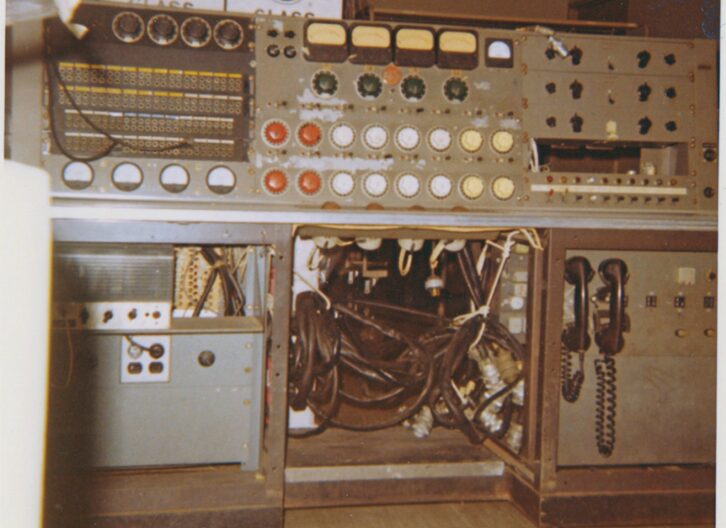

“The sound system was a three-channel [left, center, right] stereo sound reinforcement system for symphony orchestra concerts,” Blanton explains. “A fourth channel was used as a solo channel, vocal and/or instrument, patched as a mono solo over the stereo orchestra via a transformer arrangement.” For pop and rock concerts, it worked as a 3-channel mono system, again using the transformer arrangement, playing the same content in all three speaker arrays The fourth output channel could also be patched as a standby/backup in case of failure of one of the other three channels during a performance.

Mic inputs from the stage went to preamp arrays in a tall Sound Tower structure (now gone), about 25 feet forward of the Stage Left speaker tower. The preamps each essentially had three outputs, one of which sent the mic signals at line level to the mixing console, located 300 feet away, across the promenade aisle from the current mixer location, the last two rows of box seats left of the center aisle.

“The console had 20 inputs—four left, eight center, four right and four as part of the fourth solo channel,” explains George Velmer, who became the Bowl’s mixer and head of audio in late 1965. “It was a totally passive board, with classic RCA knobs; there was nothing active in it.” The mic channel assignments were hard-wired in the Sound Tower to the 20 console inputs, though they could be reassigned, if necessary, through a rarely used patch bay on the left side of the console.

“On the right was simple channel EQ, just high and low,” Velmer adds. “And each input channel could be previewed, like a ‘solo’ in a modern console, via a headphone monitor amp we had there.” The four mixer output channels returned at line level to the Sound Tower, where the signals were sent to line and power amps.

The Sound Tower also had provision for either visiting radio broadcast or recording teams, most often for radio. “We did all the broadcasts for the symphony for KFAC radio,” Blanton explains. Two bridging loss pads were employed across the two remaining outputs of each mic preamp, to reduce the output by 40 dB down to mic level and provided to any visiting broadcaster or recording company via a snake cable feed, without affecting the line level signal going to the mixing console.

Capitol Records’ second attempt to make a recording was more successful, negotiating with both the American Federation of Musicians and the Hollywood Bowl Association to record The Beatles (sans other acts on the bill). Capitol did not have a mobile unit of its own, though at the time the label occasionally rented a truck and threw in a mixer, recorders and Altec monitors from the studio. For the August 23 show, they did what many labels did in the L.A. area when doing a remote recording: They hired Wally Heider.

“They liked us showing up and doing all the dirty work, and they could just come in and engineer,” recalls veteran producer/engineer Bill Halverson (Cream, CSN), who joined Heider’s Studio in November 1964, having met him when Heider would record his high school band. Heider, had opened his own small studio at Selma & Cahuenga after leaving United/Western Studios, and had developed a solid reputation doing remote recordings of all kinds, Blanton notes. While Halverson recalls Heider originally schlepping his gear around to jobs in the trunk of his Cadillac, by the time of The Beatles’ shows, he had a converted 14-foot Dodge box truck. Inside, typically, were a pair of Ampex tape machines, including a 300 3-track similar to those Capitol was using at its studio.

“Capitol was kind of behind the times,” notes retired label engineer Don Henderson. “We didn’t get 4-track until 1966-67, and then a long time before 8-track.” Heider’s 300 was one he had acquired from Ozzie Nelson in exchange for studio time. “We did a lot of the soundtrack for The Ozzie and Harriet Show,” he says. “It was Ozzie’s 300 in the truck that recorded The Beatles.” The second machine, he notes, was a hybrid 350 or 351, which could be fitted with a 3-track head stack.

For the 1964 recording, Capitol brought two of their own 3-track 300s, but utilized the rest of Heider’s gear. The console was a 12-input, 3-output Universal Audio desk built by Bill Putnam, with rotary knobs. (It was not the famous “Green Board” built by Frank De Medio for Heider a few years later, now owned by Neil Young.) Monitoring was done via three separate Altec 604 cabinets, one for each channel. There was no air conditioning inside (remember, it’s August), but the inside was lined with packing blankets to help with isolation. The truck was positioned backstage, behind the Stage Left speaker tower, and connected via cable to the Sound Tower.

Because of union rules (Heider’s was not a member), only union stagehands could set up microphones onstage. The workhorse house mic at the Bowl at the time was the Electro-Voice 666, distinctive by the air tube along its back, to bring back pressure up to the capsule and help with wind noise. The mic was applied essentially everywhere onstage, says Blanton, who supervised the 1964 setup, with the show mixed for the house by Bowl engineer Ben Chavez. “Today you have mics built specifically for drums; we didn’t have that convenience. We just picked a good-quality mic and used it wherever we could use it.”

Not that the 666 didn’t have its drawbacks, Velmer notes. “The pickup was overly sensitive. It was a cardioid, but it was a wide cardioid, so there would be leakage from guitar amps into the vocals—which was a problem if you were also miking the amplifier, because you had the same signal going into the vocal mic, introducing a time difference, which affects the response,” something that, indeed, can be heard in the raw Bowl recordings.

The mics were placed on both John Lennon’s and George Harrison’s Vox guitar cabinets, as well as on Paul McCartney’s bass amp. Ringo Starr’s kick drum had a 666 set on a desk stand in front of the kick drum, while an Altec M20 (“The only one we had,” Velmer notes), suspended in a shock mount, was used as an overhead. Another 666 was on a boom near the drummer, swiveled into place for his one featured vocal.

Though the Bowl audio department had no need for audience mics (or “applause mics,” as they were known), a label doing a recording did like to have them. “You had an audience there, so you wanted the excitement of the audience,” says retired Capitol mastering engineer Bob Norberg. Adds Halverson, “Wally kept a matched pair of Neumann U67s in the truck, which we used on every remote I ever did. We always had them Stage Left, Stage Right, off to the side, to be clear of the sound system speakers—something I learned from Wally.” The pickup from the applause mics would nonetheless remain the bane of the Beatles’ Bowl recordings for decades to come.

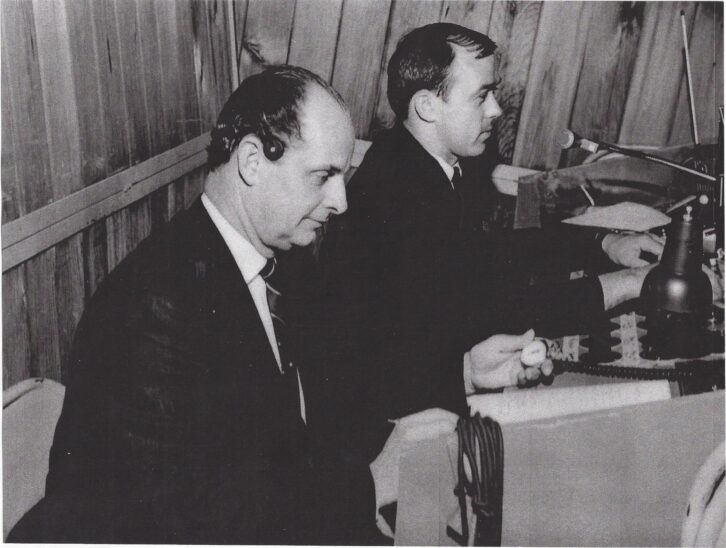

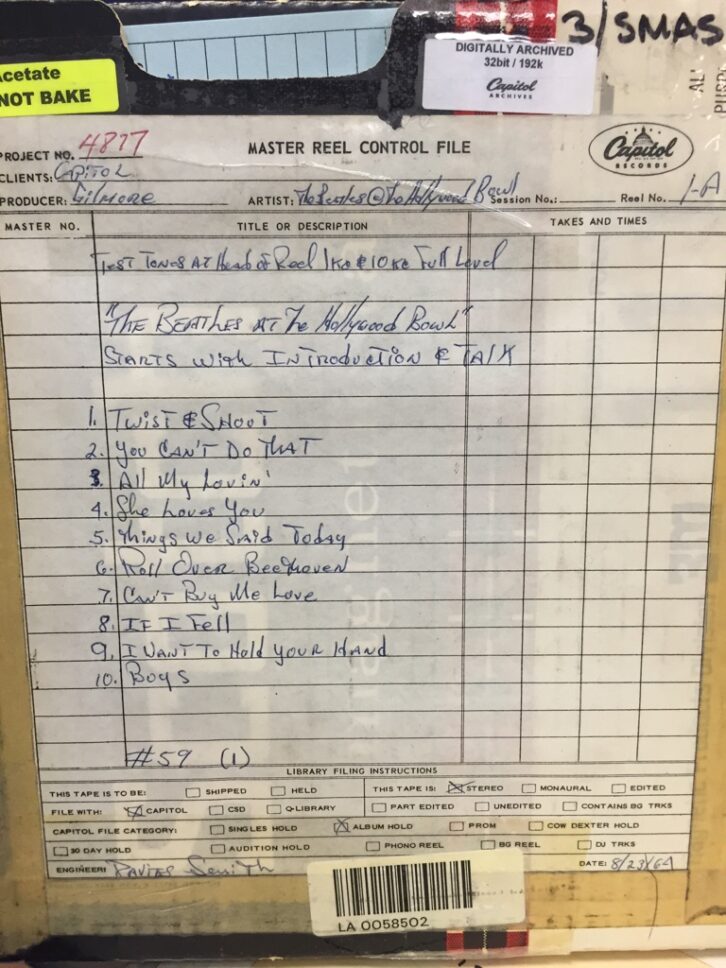

Inside the truck running the recording was Capitol staff engineer Hugh Davies, supervised by staff producer Voyle Gilmore (Sinatra, The Kingston Trio) and assisted by disc cutter Billy Smith, who would occasionally be called into service to assist on remotes. “My main job was cutting proof refs and lacquers, but I would occasionally go out on a remote to the Troubadour and others, like this,” Smith recalls, to run the tape machines and make track notations.

Davies tracked to 3-track, using ½-inch 3M Scotch 111 tape. “The old rust-colored tape,” notes Norberg. “It held up like crazy, compared to later Ampex tapes.” Davies mixed to the following track layout: (1) bass and drums; (2) vocals; (3) guitars. Harrison’s lead guitar was often picked up by the mic he and McCartney shared, which was placed just downstage from his amp. Lennon’s guitar also sometimes appeared in Track 2, picked up by his own vocal mic, similarly placed downstage from his amp, when he wasn’t blocking the sound flow while standing at the mic singing. (In the 1964 recordings, Lennon’s guitar is unfortunately mixed at a low level, compared to Harrison’s, sometimes barely audible in the guitar channel.)

The applause mics, left and right, were mixed into Tracks 1 and 3, respectively—and, unfortunately, at a fairly high level. “It used to really bother them, even then,” Smith says of the loud crowds. “I remember Ringo coming in the studio once and remarking to me about it. They were great musicians and it didn’t appear the fans really cared.” Notes Halverson (who was only present for the 1965 shows) of the screaming, “It was like the old Memorex commercials—it would push your hair back. I’ve never had sound push me like that.”

Each of the Ampex machines was running 2,500-foot reels, which, at 15 ips, would capture just a little more than 30 minutes of program. “The idea was not only to have a backup running, but to create an overlap,” Norberg explains. “Hugh explained to me: He would start the machines at the same time, but stop the ‘B’ machine five minutes before the tape would run out, allowing the ‘A’ machine to continue recording, while the tape was changed. So there was never any loss.” Adds Smith, “It was actually nerve-wracking; you couldn’t let it run out. There had better always be tape running.” The 1964 show ran just over 37 minutes (including an introduction by Eubanks and KRLA program director Reb Foster), generating two pairs of reels.

Watching from the wings were a number of Capitol engineers. Recalls veteran engineer Hank Cicalo (who, nine months earlier, had made the first test cut for “I Want to Hold Your Hand” for A & R exec Dave Dexter, Jr. to play at a weekly meeting to decide about its release), “There were five or six guys backstage. It just happened on the spur of the moment. ‘We’re going down to the Bowl, anybody want to go?’ I think we jumped in one guy’s car and went. And some of the guys said, ‘Who are The Beatles? We don’t want to go anyway.’” Also watching was Beatles producer George Martin—invited to observe only, leaving the recording process to Capitol’s engineers.

The following day, back at Capitol, Davies edited together the last two songs, “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Long Tall Sally,” off of the second “B” crossover safety reel onto the first “A” reel (whose reel had been changed after “Boys,” missing part of “Night”), creating a complete show reel. Over the next several days, he worked to create a rough stereo mix for George Martin’s review. The mix utilized EQ, limiting and reverb, the latter including a 15 ips tape delay in the send to Capitol’s famous reverb chamber. After finishing on August 27, protection copies for Capitol’s L.A. and New York studios were made of the 3-track edit, and then the original 3-track, along with Davies’s mix, were sent to EMI in England the next day.

Upon review by Martin and The Beatles, though, it was decided that the recording’s quality wasn’t satisfactory for release. “The recording tended to emphasize the crowd, so you get a lot of top end,” explains Abbey Road software engineer James Clarke, who worked on the restoration. “They may have boosted the higher frequencies and flattened out the drums, which are buried in the mix. And Paul’s bass basically disappeared. It was easy to see why EMI rejected it.”

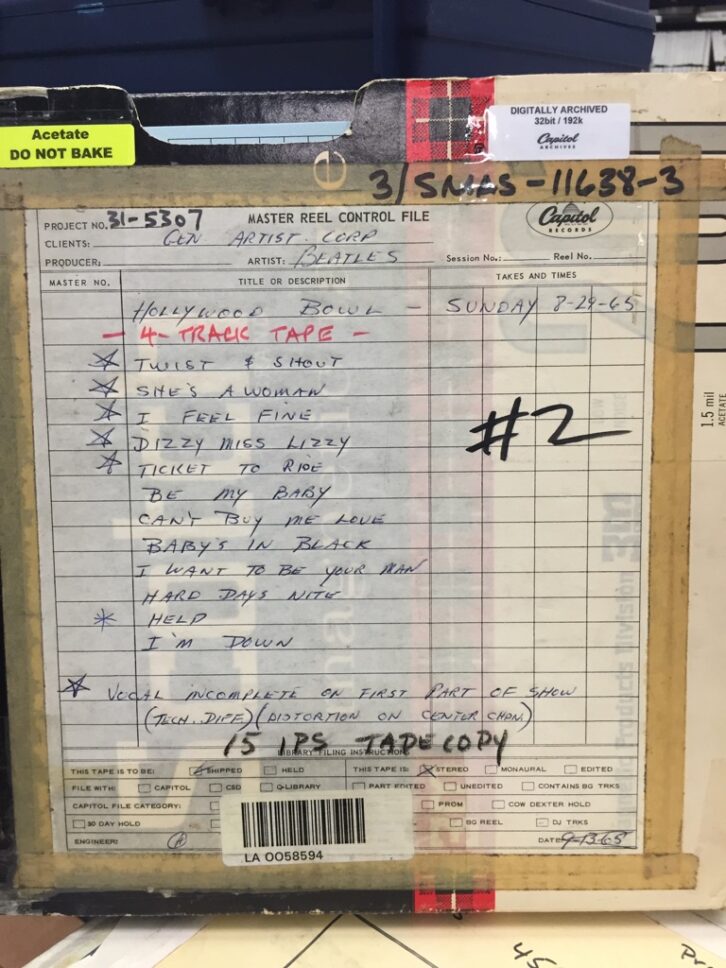

So the following year, when The Beatles returned to the Bowl on Sunday August 29 and Monday August 30, Capitol took another pass at recording, again using Heider. This time, the label brought just one of its Ampex 300s as its “B” machine, the “A” being Heider’s. “That was Ozzie’s 300 in the truck that recorded The Beatles,” says Halverson.

After rehearsals at the Bowl (which customarily took place from 9am to 12pm, after a 2 hour setup), the Fabs held a press conference in Capitol Studio A (where they received Gold Record Awards for their Help! LP), which was recorded for posterity by engineers Joe Polito and Jay Ranellucci, leaving the Tower via armored truck!

This time, in Blanton’s absence, mics were set up by Velmer (who left when his shift was over at 5 p.m., missing the show), 666s were again utilized, but with a slightly different arrangement for Ringo’s drums. A single RCA BK5 on an Atlas Sound boom stand was slipped in underneath the ride cymbal, with a mic for the kick on the beater side of the drum. “In those days, you typically had one overhead and a kick drum mic, and that was it,” Velmer explains. “So there were times we could come in from the front, at an angle, to catch the snare and toms, and be under the cymbals. That was really not unusual. It may not have been the best technique, but it was what it was.”

The second year’s shows featured an additional instrument, a Vox Continental organ, which Lennon notoriously played on the show closer, “I’m Down”; it was plugged into a second channel on Lennon’s guitar amp. “In those days, you didn’t have a direct box,” Velmer notes. “It would go through the amplifier. You wanted the effects of the preamp to give it all of that character; it would otherwise be really dry.”

The concerts were once again mixed by Ben Chavez, who this time brought his family along. “We all knew it was pretty important, so he brought us all down to see,” says his widow, Ellie. “Ben so looked forward to being out there in all that excitement.” That excitement included female fans actually climbing over the fence that separated the mixing area from the aisle behind, climbing over Chavez and the console itself to get to the pool in front of the stage to try and get at The Beatles. “That happened to me more than once,” Velmer recalls. “It happened so fast I didn’t even know how they did it!”

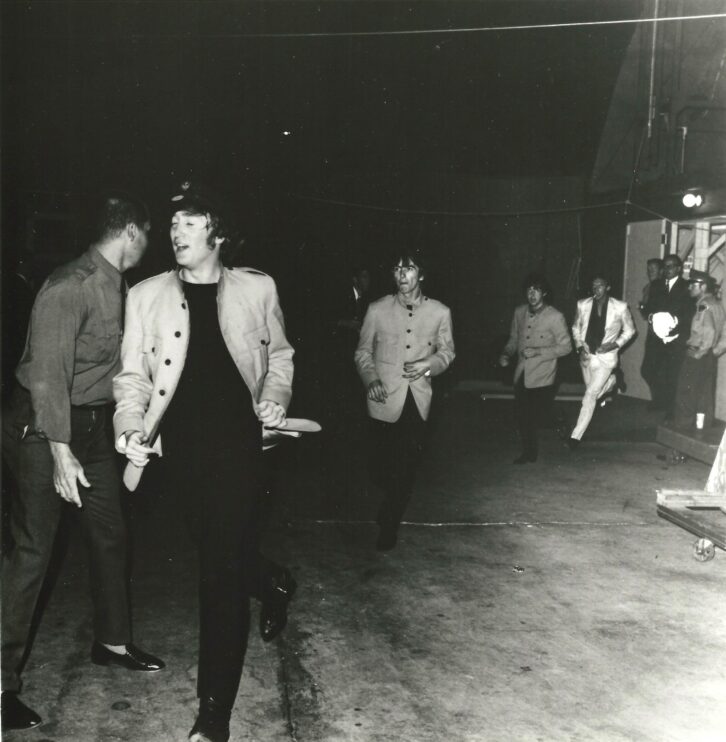

During the show, the recording engineers were left to themselves, Heider and Halverson watching the show from outside the truck. “Wally took a pretty good whack in the shins from a girl who was trying to climb over a barrier, when The Beatles were leaving the stage for an ice cream truck we had for them,” Blanton remembers. “When he tried to break her fall, she got him pretty good!”

The following year, when the Beatles returned to the Bowl, the system on August 29 experienced a technical issue that rendered the first part of the recording unusable. The mic cable connection of Paul’s/George’s vocal mic, somewhere between the Sound Tower and the truck, was apparently unplugged or disconnected for the first four songs, the error realized and repaired in time for “Ticket to Ride” (the signal apparently did make it to the house mixer—the audience can be heard reacting to McCartney’s conversation with the crowd, picked up faintly by other mics, as heard in the raw recordings). The band’s performance for the remainder was somewhat uneven, and a 60Hz hum/distortion could be heard throughout, so the following night’s show was also recorded.

Though engineer Pete Abbott has long been credited as Capitol’s on-site engineer (as first seen in the sleeve notes for the 1977 LP), no evidence on the tape boxes indicates this. Instead, Davies (with his signature “H” in a circle in the “Engineer” field) and assistant Mike Martin appear to have tracked the date (again under Gilmore’s supervision), as noted on all the 1965 tape boxes. (Technical Studio Report [TSR] session records would have identified the engineering team, as well as technical info, but the studio’s entire collection was tossed in the early 1980s, according to Norberg and Henderson.)

Eubanks once again introduced the band, this time joined by five other KRLA jocks, including Casey Kasem and Dave Hull. “So that no one would feel slighted at somebody introducing them by themselves, we collectively decided that we would introduce them together,” Hull explains.

The recordings were apparently equally deemed unusable for release, just like their predecessor. “It’s funny, there isn’t a huge difference between the ’64 and ’65 recordings,” says Giles Martin, son of The Beatles’ original producer, George Martin, and producer of the current remix of the recordings. “I can just imagine my father’s frustration—‘Didn’t you learn anything from the previous year?’” he laughs.

The project laid idle, though a copy of the 1965 recordings was dubbed onto 8-track in April 1971, perhaps with consideration for release then. On March 24, 1976, Capitol staff producer John Palladino assembled an album, Beatles at The Bowl, drawn from the second 1965 show, with “Twist and Shout” through “Ticket to Ride” on Side 1 (TRT 14:06), and the remainder on Side 2 (18:45). The tape was even mastered, but it, too, never saw the light of day.

In January the following year, Capitol decided to move things further, asking George Martin to review the tapes for release. He and engineer Geoff Emerick copied the three shows’ worth of 3-track recordings to 8-track, and then spent several weeks processing/mixing them at AIR Studios in London. They eventually created an assembly of tracks selected from the 1964 and second 1965 shows (including Eubanks’s band intro from that second show), skillfully mixed and crossfaded to offer, essentially, a single Beatles show. The album was mastered at Capitol by Emerick and Wally Traugott on February 28, with final mastering coming a month later. The album was released on May 5, an immediate treasure for Beatles fans who had waited so long to hear the band live.

deMIX AND RESTORATION

In 2012, as The Beatles’ Apple Corps Ltd. was beginning to get the ball rolling on Eight Days a Week, restoration of the Bowl recordings once again commenced.

“I listened to the album my dad made in 1977, and, with today’s ears, I don’t think it’s good to listen to, sonically,” says Giles Martin. “The ambition we had was, could we make a Beatles live album that was good to listen to? And I think with the kinds of tools we have available to us today, we were able to create an album that’s better than if you were standing in the Hollywood Bowl listening to The Beatles in 1964 or 1965. We tried to peel back the effects of the technology at the time and try to get closer to the experience.”

The most significant technology advance came about when, in 2010, James Clarke, a software analyst looking after the business systems at Abbey Road, had a chat on a break with senior engineers Peter Mew and Allan Rouse. “I asked them, ‘Is there any software that can unmix recordings?’” Clarke says. “They all started laughing, and said, ‘That’s the holy grail of the recorded music industry, and it’s not possible.’ So I just thought, ‘Well, if the human ear can do it, then software should be able to do it.’”

Clarke, who has a physics degree from University of Wai Kato in New Zealand, began studying the literature on blind source separation, which allows software to track a face through a video. “They realized, when they applied it to music, that they could use the spectrogram to do exactly the same thing,” the engineer explains. He began writing code himself and getting good results, prompting Rouse, who was the shepherd of Beatles projects at the studio, to try the system on one of the few Beatles tracks for which no multitracks exist, only mono mixes—“Love Me Do”—eventually creating a fairly good stereo mix, separating the harmonica from the guitars, etc.

The system, which Clarke calls deMIX, works with a combination of spectral and power models of whatever an engineer wishes to create a separation for. Clarke first creates a spectral model of an instrument, for example, Starr’s drums or McCartney’s bass, from Beatles multitrack recordings available to him in the Abbey Road vault. That is accompanied by a power model of the same recording, which matches the spectral model. “When you have overlapping frequencies, the only way to distinguish whether it belongs to a guitar or to a bass is by its power spectrum,” Clarke explains.

When the program is run, it creates an array of 300 or 400 “atoms” of the item Clarke is attempting to separate in a recording, via a Fourier Transform of that recording, and compares it to a Gaussian distribution of the model he’s built of the instrument. “It says, ‘Well, this little atom matches the spectral and power fingerprint that belongs to the drum. So it more likely belongs to the drum than it does to the bass guitar,” he explains. “So I then cluster all these broken up samples to the instruments I want to grab out, and just iterate over and over and over, throughout the entire length of the song, until it decides, ‘Yes, that is the drums.”

A technique known as Weiner Filtering essentially uses binary mask created by the separation process, digitally filtering out everything of the original wave but the instrument being sought, after which, a Fourier Transform turns what remains, digitally, back into the waveform of that individual instrument. That is done for each instrument in the original wave, creating separate wave files for each instrument in what was a single track. All of those can then be phase-inverted and combined back with the original wave, as a test for success. “If we get a flat wave, we know it’s worked properly,” says Clarke.

Processing of a single song file, such as the 1.5-minute “Twist and Shout” from the Bowl, takes about three hours, a vast improvement over the two years that Martin and engineer Paul Hicks spent creating the “demixed” audio tracks for The Beatles Rock Band, released in 2009. For that project, the team used Cedar ReTouch to painstakingly paint out bits of instrument wave off spectrograms of Beatles session recordings to get isolated tracks.

So with that in mind, when Eight Days work began in earnest in 2012, Martin asked Clarke to try his deMIX system on the Bowl recordings to help with the most difficult challenge: the audience screams. “I did the same thing with the crowd noise as I did with the instruments,” he says, taking samples of the crowd from moments of Bowl recordings where the crowd was screaming but no music was being played, of which there was plenty, to build his spectral and power models of the screams, and treating them as if they were an instrument. “I’ve got loads of examples of just the crowd cheering away,” Clarke notes. “The more samples you have of an instrument you’re trying to model, the better your fingerprint will be.”

The result, using deMIX, was a clean track of the audience screams, which could then be mixed out of the tracks on which they appeared (Tracks 1 and 3), leaving just the instrumentation. Clarke similarly was able to use the system to separate McCartney’s bass from Starr’s drums on Track 1, offering yet more flexibility, though Harrison’s and Lennon’s guitars, on Track 3, couldn’t be separated, because the spectral/power models of their two guitars are simply too similar.

The deMIX’d tracks then allowed Martin and Okell to do their magic. “When you take the sound of 16,000 screaming girls out, it gives you a much cleaner guitar track or bass track to work with,” Okell notes. “That’s partly how we get so much more clarity in the mixes—we could duck down and EQ the guitars, without EQ-ing the crowd.”

“The reason the original vinyl album sounds dull,” Martin explains, “is the reticence of my dad and Geoff Emerick to add any top end to it, just because of the screams. If you brighten the drums, you brighten the screams. The crack of a snare drum is between 2 and 3 kHz. If you add that, that’s exactly where the screams hurt your ears. And you could forget about compression; it just made things worse.”

Okell notes that while Martin’s father and Emerick had applied slapback reverb to give a sense of the size of the venue, to offset the otherwise dry close-miked recordings, he and Giles made use of authentic gear, such as Fairchild limiters, tube reverb plates and Abbey Road’s legendary reverb chamber, as well as another tried and tested method: “We’ll also do re-amping—playing the track out of loudspeakers in Studio 2 and recording it back from the other end of the room. That’s particularly useful when creating a 5.1 surround mix for the film. It’s a matter of giving it some size without feeling like it’s just smothered in cheesy reverb.”

After processing, the whole recording can be reassembled—with the screams added back in at a more palatable level. “It’s a bit like baking a cake,” says Martin, “and realizing you want to add more eggs. The cake isn’t going to be a cake if you just add more eggs. You have to put the whole thing together again, which is what we had to do.”

The Beatles at Shea—How the First Stadium Concert Was Recorded

As for track selection, Martin followed the same path his father took: processing and mixing all the tracks from all three shows and then selecting the best. “I hadn’t really been thinking about what was on the original LP,” he says, “and then, I wasn’t surprised that Sam and I made almost exactly the same choices my dad had made with Geoff Emerick.” Even though an additional four songs were deemed of high-enough quality to include, Martin decided to leave the running order intact, with the same 1964 and 1965 tracks interlaced the same as before, adding the new songs as bonus tracks. “I thought, ‘We might as well make this a celebration of his work.’ The only reason to have inserted those other songs in some other order would have been ego—‘This is my version of Hollywood Bowl’—and that didn’t make any sense.”

Consideration was made to use the 1965 closer, “I’m Down,” as the album closer, but it was found that the first night’s recording was marred by distortion, and the second night featured a performance flub. A brief attempt at using some elements from each night to create a blend was made, but ultimately rejected, as was the case with other tracks. “Things like lead parts that just aren’t there or almost inaudible or obvious technical flaws ruled things out for us,” Okell explains. (One such edit was successfully executed, borrowing a lead guitar break from the August 29 recording of “Dizzy Miss Lizzy” to fix a low-level spot in the August 30 track.)

“The purists, of course, want us to release all three shows in their entirety, but we’re not releasing a flawed performance. If you release a Beatles album, whatever it is, that comes with a certain level of quality that people expect.” Adds Martin, “Music’s not for collecting, it’s for listening.”

The result, Martin says, “is a snapshot of the peak of Beatlemania. What you hear now is how much fun they’re having when they’re playing. They were musicians, first and foremost, and I think that’s what you now can hear.”