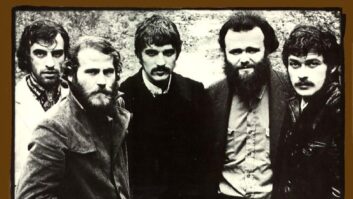

Left to right: Ulises Bella, Justin Poree, Jiro Yamaguchi, Asdrubal Sierra, Wil Abers, Raul Pacheco.

Photo: Matthew Whittington

Famously energetic and fabulously eclectic, the L.A. band Ozomatli shows no signs of slowing down after close to two decades of practically nonstop action. The group has taken its dynamic and infectious fusion of rap, rock, funk, reggae, Latin, jazz and other styles all over the world—sometimes as cultural ambassadors sponsored by the U.S. State Department—including far-flung destinations in central and southeast Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, Australia, Mexico and South America. They’ve played many big and small U.S. festivals (Bonnaroo, Coachella, etc.), regularly headline in clubs, theaters and assorted venues all over the country, and have landed songs on film soundtracks and TV shows. It’s a wonder they ever have time to record an album.

Indeed, producer/engineer Robert Carranza, who has helped record every Ozomatli project since their first EP in 1997, says that the group’s latest studio effort, Place in the Sun (Vanguard Records), had to be cut over a long period of time in between the group’s tours and other obligations. However, “that actually worked to our advantage,” he says, “because it gave us some perspective on what we’d already done, and we ended up changing some things and making them better.”

To hear Carranza and guitarist and singer Raul Pacheco tell it, making an album the Ozomatli way can be quite a complicated process. Some songs start with a sequenced rhythm part, others with a synth bass, or a guitar or keyboard; there’s no fixed way of working, but once the ideas start to flow, everyone participates in developing them, both on their own and as a group. They share group writing credits throughout.

“At this point, everybody in the band has a studio” Pacheco says. “That’s what was interesting about this record—the disparate sources and disparate quality of ideas.”

“There are so many people coming at you with different stuff,” Carranza adds with a laugh, “but the guys have become very adept at Pro Tools and actually recording sound. One of the things I keep telling them is, ‘Look, sometimes the sound doesn’t matter.’ It’s the intention of the sound. The feeling that it gives you is more important than whether this trumpet sounds really good or not. I’m a big believer that it’s more about the inspiration than the microphone. If the microphone’s there, it will capture the inspiration coming through. And that happens a lot with them.”

Pacheco adds, “When you bring all these sources to a guy like Robert, it gives us a lot more options: Here’s this demo vocal, but it sounds kind of trippy and cool—is there a way to use that? Or this sample? Or this guitar part? What we did on this record is we made these demos and then we’d go in and play, as a band, at a place like EastWest [in Hollywood]—beautiful, great-sounding rooms—and then we’d find we could layer some of that demo stuff underneath it. So, on songs like ‘Prendida’ or ‘Tus Ojos,’ there’s a mix of electronic and live stuff, and finding that balance is something Robert really has a skill for. Sonically, those are some of my favorite things—it sounds really new, but you can also tell there are live instruments in there. That mix is current and cool and exciting.”

Carranza estimates that about 80 percent of the album was tracked in the Neve console-equipped Studios 1 and 2 at EastWest, with most of the rest of the work (and the mixing) done at Brushfire, Jack Johnson’s solar-powered studio in an old L.A. craftsman house, where Carranza has a room equipped with an SSL AWS 900 console. (Carranza has also engineered and mixed many projects for Johnson, as well as such artists as Mars Volta, Sublime, Los Lobos and ALO.) One song on Place in the Sun, “Brighter,” was produced by Dave Stewart.

Texturally, a number of songs on the new album are dominated by decidedly retro-sounding synths and keyboards, contributions from the creative minds of multi-instrumentalists Uli Bella and Asdrubal Sierra. “On this record,” Carranza says, “I’d say about a third is soft synths, a third is real Moogs and other hardware-based keyboard stuff, and then some of it from the iPad—from GarageBand or whatever. Again, for me, the inspiration is more important than the source of the sound, so it was like, ‘Great let’s use that!’”

There was much experimentation along the way, looking for the right instrumental textures for each song—whether it’s the ’40s-sounding horn section on “Echale Grito”; the electrified and fuzzed Cuban tres guitar on “Burn It Down”; the pulsing, jacked-up electronics on “Ready to Go”; or what sound like dueling Farfisas on the sunny title track. There’s a lot going on in these songs, yet somehow they never sound cluttered, and the detail doesn’t intrude on the fundamental simplicity of the group’s approach, which emphasizes bright melodies, solid hooks, contagious rhythms and positivity at every turn.

Pacheco says, “I think what’s made us be successful in front of large crowds that have no idea who we are, and also on our albums, is that we’re ultimately a dance band. People like to move and dance; rhythm is the key natural human element of it all. We have a crazy energy, especially live. On records, too, we want to keep it interesting, with a lot of different styles, but always keeping some momentum, because we’re a groove-oriented band and always have been. We want to take the listener on a journey.”

More from guitarist/singer/songwriter Raul Pacheco and engineer/producer Robert Carranza about the making of Ozomatli’s Place in the Sun album.

Pacheco on Carranza: “I’ve known Robert since he was 14. We were in a heavy metal band for a moment. He was the drummer; we both had crazy long hair. I mostly knew him in high school from playing in local bands at parties. At some point, though, he got into engineering, and even before I was in Ozomatli he was engineering. He was interning at Track Studio in North Hollywood and showing up at midnight when everyone was gone, and learning how to do stuff with little bands.

“Robert’s great: He’s one of the guys who “gets” it—who understands the crazy process of making a record with us. And have the ability to make it sound like that’s what we meant to do.”

Pacheco on what the band has learned from working with other producers, such as K.C. Porter and Steve Berlin: “The general perspective we’ve learned from other producers is just how to make a record—the whole process of writing songs, which start with ideas, and then fleshing those out into complete songs, seeing which parts are good and which parts are bad; knowing when to say, “This song is not right for us.” Those are things we’ve learned over the past 20 years, working with different people. What’s great is that everyone has his own take on it.”

Pacheco on songwriting: “There is no set way of working in this band. We have enough experience working all sorts of different ways. We just look at the tune and deal with it however it seems right. If we started a song in the room playing together and that’s what the vibe is, cool. If it started on [percussionist/rapper] Justin [Poree]’s little computer in Pro Tools in his kitchen, messing around, that’s cool, too. There’s no method to any of that madness. We just sit back and say, ‘Is this good, is this cool?’

“A lot of us are working on computers and using MIDI stuff. It’s so regular now. A lot of them started with synths—bass patterns. And Wil [bassist Wil-Dog Abers] will put something down and later we’ll decide, ‘Should he put a real bass on top of that? Do we put a real bass on one section, bring the electronic bass back in the chorus?’ We’re always looking at the movement of the song in those terms, and all those combinations are the types of choices we have.

“We’re trying to create momentum in a song, and I’m a proponent, especially in a song like [the ballad “Only Love”], that has repetitive sections, there needs to be something different happening in each section, a build-up and a release. The second verse should sound different than the first verse. A song like that is so different for us. It’s more straight-ahead, campfire style. So how do we make that us?”

Carranza on the special relationship built from years of working with Ozo: “There’s a real sense of familiarity, and sometimes you can push their buttons and get them going. [Laughs] With a band that’s been together for a long time and someone who’s been working with them for a long time, you can get complacent. On this particular record, there were some fires to be lit and fires to be put out. Together we all recognize what needs to be done. There’s an instinct that comes into play. It’s like putting on really comfortable shoes: You start taking a walk in them and it’s effortless.

Carranza on “Echale Grito,” with it’s old “mambo horns,” and newer funk elements: “Ozo is known as a band who bring in a lot of different genres of music, and I think accidentally—in the sense that it wasn’t a master plan of mine or theirs—they started getting into learning about Pro Tools and learning more about sound, and they were asking, ‘How did they record horns back in the old days?’ They were curious. When we did the kids EP [Ozokidz, 2010], I think they felt a little more freedom to have fun with stuff, and that approach kind of morphed into this record: ‘I really want this Big Band horn section where you hear the guys go “Yeah!” in the background and it sounds like it’s in a room.’ That kind of blazed a trail for us.”

Carranza on mixing the album: “I mixed at Brushfire on a little AWS [console] I’ve had for a few years. I think you can mix on anything. I’ve mixed in the box and I’ve mixed out of the box, and either way I can get something to work, but basically I’m still an analog person. A lot of the reverb your hearing on the album is actually the room at EastWest. And their chamber sounds incredible, too. When we were doing live band—and later when there were some horn overdubs—we put some room mics up and a little chamber on it and that’s part of the sound. I usually had a Coles as the direct mic [on the] trumpet, and a [RCA] 77 on the sax, and the room mics were two [Neumann] 47s and two 251s as well; because I want something off the floor and something off the ceiling. It gives it a nice dimension and space. A lot of people talk about the real direct sounds from some of the records I’ve done; real in your face. But I also really love a sense of space. I also love old reverbs. I have a [Lexicon] PCM 60 that I use a lot; I keep re-buying them over and over again.”

Carranza on mics for singing vs. rapping: “As far as I’m concerned, you can put a [Shure] 57 or a [Neumann] 47 on a great singer and it’ll come across. I don’t care what it is. I’ve got some great Gefell mics, and I’ll throw those up. Wil-dog has a Manley reference mic we used a lot on the record. It didn’t matter. It was Bill Botrell-style.”

Carranza on getting a production credit on this album: “I’ve been around a long time with the band and I feel like they have a lot of respect for me. Even when we were doing the early stuff—I did their first EP—I had a vision for what the guys were. There’s an energy to Ozo onstage that you can’t deny. I’m still trying to figure out what it is about that band live that needs to happen in the studio. We’re close to getting that. It’s a great collaboration because they can actually produce themselves on their own, so my role was sometimes more like a drill sergeant: ‘There’s this thing that needs to be done. Let’s do it!’”

Carranza on how songs evolved over time: “There are a couple of songs that were way further to one side than where they ended up. I think what happened for us was taking the break [in the middle of the process] helped out a lot. They came back—after three or four months—and we brought the tracks up and it was like, “Oh, this is terrible.” It wasn’t really, but it sounded different. We had thrown everything in it, so then we started to pull things back. This is something I would encourage other [engineers and producers] to do. Take stuff out and listen to the track. Put different instruments in for the intro than you might normally use. It’s a good way of listening—pull stuff off, put stuff in, solo stuff. All of a sudden you hear a different perspective of what that sound is, or even what the song is. You have to be open to letting it grow and evolve.”