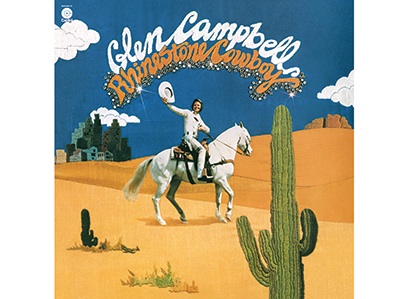

By the time 1974 rolled around, it had been five years since Glen Campbell had had a hit. The theme song to the film True Grit had received Oscar and Grammy nominations in 1969, which followed hit singles the previous two years, “Gentle On My Mind,” “By The Time I Get to Phoenix” and “Wichita Lineman” (the latter two penned by Jimmy Webb). His hit CBS variety series, The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour, last aired in June 1972.

Campbell was still a Capitol artist in April 1974 when, while driving in Los Angeles, he heard a song on KNX-FM by an artist named Larry Weiss, titled “Rhinestone Cowboy.” Immediately identifying with the song’s sentiment about a country boy navigating the music business, he rang his secretary and had her purchase a cassette of Weiss’s recent album, Black & Blue Suite, on 20th Century Records. A little over a year later, it would be Campbell’s version of the song that would be on the radio and, by September, reach the top of the charts.

In mid-1974, a team of hit-making producers, Dennis Lambert and Brian Potter, joined Capitol Records as staff producers (and working under their own shingle, Haven). Lambert had moved to L.A. in 1968 to work for producer Don Costa, whom he convinced to bring Potter over from England the following year. The two began a songwriting and, soon after, producing partnership that would last 11 years, first for T.A. (Talent Associates) Records with Steve Binder, and then under Steve Barri for three years at ABC/Dunhill Records. Between the labels, they signed and/or produced hits for Seals & Crofts, The Grass Roots, The Four Tops (“Ain’t No Woman [Like the One I Got]”) and Dusty Springfield, before leaving for Capitol.

The producers were already busy at work with the label’s new R&B artist, Tavares (“It Only Takes a Minute”), when marketing and promotion executive Al Coury asked them to produce an album for Campbell. “I think he thought it was a real stretch for us, since we were doing a lot of R&B,” Lambert says. “But, to his surprise, I loved Glen, and so did Brian. Brian was a little concerned because he thought Glen’s roots were deeply in country, but I told him, ‘No way. He’s a country boy, but he lives in L.A. He’s a pop crossover guy, one of the first.’”

The three met up at Campbell’s house around November 1974, both to get to know each other casually and to talk about music for the project. “We were thinking about a cross between pop and country—a mix of ballads and rhythm songs,” some of which Lambert and Potter would write and others they would find.

Not long after that meeting, Larry Weiss—who, it turns out, was an old friend of Lambert’s from their earliest days as songwriters in New York—contacted Lambert for a meeting. While Weiss’s single had briefly peaked at No. 10 on the Easy Listening chart, his album had all but disappeared. “I didn’t know he had made an album, but he brought it up to my office and played some songs for me,” one of which was “Rhinestone.” “I was listening to it, and I’m thinking, ‘This sounds like the story of Glen’s life.’ The metaphors were perfect, and it had interesting lyrics, plus rhythmic components his earlier work didn’t have. I thought, ‘This could be Glen’s theme.’”

Within the week, Lambert played the song for Campbell, who didn’t respond, except with a slight smirk. “As soon as it finished, he said to me, ‘I know this song. I love this song,’” Lambert notes.

During the years prior to their work for Capitol, Lambert and Potter would often record at United Western Recorders, typically working with engineer Joe Sidore, starting in 1969 with The Original Caste’s “One Tin Soldier,” the theme to the film Billy Jack. Sidore had gotten his start at age 20 in 1961 at a small demo studio at Sunset and Vine called Harmony Recorders, where he learned not only to record but to master, as well. He would often, in those early days, run into young Glen Campbell, who would provide not only guitar but also vocals on those songwriter demo sessions. [His first actual session for Campbell, as an artist, was in 1969, on “True Grit,” at Western Studio 3.]

Sidore started at Western in 1964, eventually going freelance in 1971 (among the first engineers to do so). “Joe became ‘our guy,’” Lambert recalls. “Not only was he an incredible engineer, with great ears, and a true gift for recording, having come up under the likes of Chuck Britz and Lee Herschberg at Western, but he was also a great mastering engineer. We’d finish mixing, and he’d go, ‘Let’s go master it,’ and we’d go upstairs to the second floor, and he’d cut it.”

With their success and recent move to Capitol, Lambert and Potter began looking for a new home base from which to create their recordings. Armin Steiner had opened Hollywood Sound Recorders around the corner from Capitol in 1965 and, a few years later, opened Sound Labs, just across the street. The studio, built by Steiner and acoustician John (Jack) Edwards, was constructed on the second floor of an office building, notes former chief engineer Pete Barth, who left A&M Studios to join up with Steiner not long after Studio 1 was constructed.

Steiner first built Studio 1, a small overdub/mixing room, featuring a custom-made console built by Cal Frisk, using Opamp Labs components. “Armin did something unique with that console, which is he didn’t have pan pots; he had panning buses,” Barth describes. “You had left-center-right that you could select on an input module. But the left-center-right that you selected could either be 3dB outside center, 5, 7 or 9 dB outside of center. There was no sweep—except on one module, for an effect. We wanted the console so clean that it wouldn’t add distortion at all. And that’s how we did it.”

The room also featured among the first 3M M79 24-track tape machines, Serial No. 2 (Wally Heider received No. 1), plus Scully 280 2-tracks and mono ¼-inch for mixdown and tape slap, all of which had their transformers removed, and the Scullys were highly modified. Steiner placed a pair of Altec 604 speakers in the ceiling soffit, something that hadn’t been done before, according to Barth.

Not long after Studio 1 was built, Steiner noticed a large vacancy elsewhere on the second floor and decided to build a 1,000-square-foot tracking room. “It had a low ceiling, because it was in an office building,” Barth says. “But Armin’s acoustician designed the floor in a manner similar to that used on airplanes.” The flooring system featured a plywood base atop the concrete deck, upon which were placed 2-inch Fiberglas pucks covered in silicone, on which were set rows of steel channels, with the floor deck on top. “It was only about four inches deep,” he says. Walls were built of heavy panels of drywall with four-pound lead sheeting, whose edges Barth soldered together, to essentially create an RF shield.

“It was pretty dead,” Sidore notes. “You had to know where to set things to get the sound you were looking for. There were a lot of dead areas with standing waves.” Notes Lambert: “Joe had to work a little harder to get a good sound, but he was so good, it went from being just a room in an office building to something that sounded great.”

The control room featured a 36-channel Quad Eight console, built to Steiner and Barth’s specs after a visit to the company’s offices with a list of their specs. “It was a balanced nontransistor semi-bus design, with no input transformers in the line amps, which they custom built for us,” he explains. “It was so transparent, engineers like Eric Prestidge and Bill Schnee would bring their own U 47s, U 49s, because they wouldn’t use outboard preamps, because they liked the console.”

The main tape machine was a 24-track Stephens (supplemented by a Studer A80). The machine could be fitted with either a 16, 24 or a 32-track head stack. “Stephens was a master designer, brilliant, but maddening to work with,” Barth reveals. “He would insist on being the one to repair the machine, personally, if it failed. I loved and hated that man at the same time, but that machine was magnificent.”

The studio had a live reverb chamber on an upper floor, though Barth and mixers were not above utilizing the building’s elevator hoistway for additional reverb. “People in Studio 1 and 2 would fight over that echo chamber,” Barth says.

Tracking a Cowboy

Basic tracking for what would become the Rhinestone Cowboy LP began with the recording of its title track, plus two other songs, both ballads—“We’re Over” and “I Miss You Tonight,” the latter written by Lambert Potter Potter, the former by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. The session took place in Studio 2 on Monday, February 24, 1975, just after completion of another Lambert and Potter record at Sound Labs for The Righteous Brothers.

“We’d usually only do three songs with a rhythm section on a ‘double-date’—six hours instead of three—so we would give every song a full two hours,” Lambert says. “We never wanted to settle, by rushing them through a single session.” Even though “Rhinestone” was the likely lead track, “We’re Over” was tracked first, followed by “Rhinestone,” and then “Miss You.” “You wouldn’t want to have the guys do two ballads in a row, ‘cause it’s hard to get them out of that fog. I’d start with a ballad, then get some blood flowing, and then go back to a ballad.”

“The guys” included a who’s who of top L.A. session players of the day: drummer Ed Greene, guitarists Fred Tackett and Ben Benay, and bassist Scott Edwards. Lambert typically used pianist Michael Omartian, who was apparently unavailable for the session, so David Paich—who, just a few years later, would help found Toto— handled the song’s piano track, uncredited until now.

Paich grew up around Campbell. His father, Marty Paich, was musical director for the singer’s variety show for five years, and it was Campbell who recorded Paich’s first hit record two years earlier, “Houston, I’m Coming to See You.”

When he arrived at the studio, Paich also found a familiar instrument. “It was a Hamburg Steinway that belonged to Armin’s mother,” the musician recalls. “He used to have it across the street, at Sound Recorders,” adding that it was Steiner who found Paich his first piano teacher, at age 13.

While it has been assumed that Tackett and Benay both played rhythm acoustic guitars on the tracking date, with the electric guitar handled by Dean Parks on a later overdub session, the track sheet reveals that it was Benay who played the Duane Eddy-style electric part that day. Two acoustics are heard in stereo on the recording, and a 12-string is indicated on the track sheet for the session, apparently from the tracking date, suggesting it may have been Campbell himself playing along.

“He was there,” Paich recalls. “I remember him telling us some Roger Miller jokes—they used to play practical jokes on each other.” Though no one can recall for sure if Campbell did play on the track, Lambert notes, “He sat in and played on a lot of tracks. I said to him, ‘Glen, this will be so important for getting everybody fired up, if you would come in and play on the tracks,’ and he said, ‘Okay,’ and he did. And the guys loved it. He was one of them, back in The Wrecking Crew.”

The team of musicians was playing from charts by arranger Tom Sellers, who also did string and brass arrangements for the album. “He was a young guy who had just moved to L.A. from Philly right around that time,” Lambert recalls. “He had worked there with [producers/songwriters Kenneth] Gamble and [Leon] Huff and soul producer Thom Bell,” and was recommended to Lambert by Sidore, who had worked with him previously.

“Tom’s arrangements were such that nothing ever stepped on the vocals,” Sidore says. “And nothing was ever in the same range as Glen’s vocal. He did an excellent job.” A small team of copyists prepped the music for the musicians, Bob Ross and Berwyn Linton. “Bob was the guy in town for music copying,” Sidore says. Ross, former owner of Harmony Recorders, had given Sidore his first engineering job 14 years earlier.

The following day, Sidore pulled the master takes from each of the three songs and assembled a master reel for additional tracking. The next day, Lambert recorded a set of guide vocals for each, both for Campbell and for overdubbing, which would take place next.

On Thursday, February 27, percussionist Gary Coleman added tambourine and a snare and cymbals overdub to the song. A week later, on Wednesday, March 5, session guitarist Dean Parks—who had, coincidentally, played on Larry Weiss’s original version—added what are likely simple guitar “chinks” (or “chicks,” as Sidore prefers to call them) to the track, adding true electric lead guitar to the two other songs that day.

That Friday, a string session took place in the morning, followed by a horn overdub in the afternoon. The strings were contracted and led by the legendary Sid Sharp, whose string section Lambert affectionately dubbed “The Boogie Symphony.” “Sid was not only talented as a classical musician,” the producer says, “but was such a refined gentleman. And he had a great appreciation for the music of the day,” sometimes providing strings for a Sinatra date, and later in the day, for a Beach Boys recording. “He had a great appreciation for talent, regardless of the form it took.”

Though the string section was a 6-4-2 group of violins, violas and celli, it sounds much thicker on disc. “I’d record one pass on one channel, and then another take on a separate channel,” Sidore states. “Having only two tracks available, and wanting to get a bigger sound, I decided to record them in mono, one on each track, and mix them later, in stereo, which created a nice, full sound.”

The horn section was an amazing collection of top players, including Chuck Findley, Lou McCreary, Don Menza and Tom Scott. [Only flutes appear on “Rhinestone,” likely by Scott and Menza.]

Lambert himself added two additional overdubs, on an unknown date—a “low piano note,” a left-handed piano part emphasizing the run at the end of each chorus, and a Clavinet, which produced a glockenspiel-like sound in the choruses. “I remember having that conversation with Dennis,” Sidore recalls. “That gives it a sparkle—rhinestones.”

Campbell recorded his lead vocals—and a harmony, in the case of “Rhinestone”—onto the three tracks on Wednesday, March 19, during a five-hour afternoon session, using Sidore’s personal tube Neumann U 47 microphone.

While the engineer notes that Campbell would sometimes use headphones when tracking vocals, leaving one cup cocked off one ear to allow him to hear his voice in the room, for this recording, the singer requested a favorite technique. “He liked to use a pair of small Auratone 5C Sound Cubes, which I would set up on either side of the mic, facing each other, and set out of phase with each other. And since the speakers were out of phase with each other, the sound would cancel at the microphone, and nothing would be heard but Glen’s voice.”

The technique was so unusual to Lambert, the producer recalls, “I said, ‘I have to come out there and listen. How can he phrase to this?’ It was so soft. But that was Glen—the master musician and the master technician. It took me one minute in the studio to reconfirm how great a singer he really was. The moment he started, I was floored.”

Two days later, on Friday, March 21, background vocals were added to the two other tracks, and, that afternoon, Sidore mixed the songs in the Studio 2 control room. Campbell, meanwhile, was a few blocks away, recording two other songs with a group that included members of his own band, as well as drummer Jim Gordon and fellow Wrecking Crew member, bassist Carole Kaye (and a string section), at Hollywood Sound Recorders, at its new location on Selma Ave.

The single was finally released two months later, on May 26, 1975, entering the charts at No. 81, and topping them 14 weeks later.

Lambert and Potter took the months between the mix date and the beginning of June to compile the remaining songs for the album, while also working with other artists, including The Grass Roots and Tavares. They returned to Sound Labs on June 2 with the same group of session players—though this time with Omartian, the credited keyboardist, on the sessions—recording through the month. The album was released in mid-August, just in time to see its lead track make its artist a star once again.