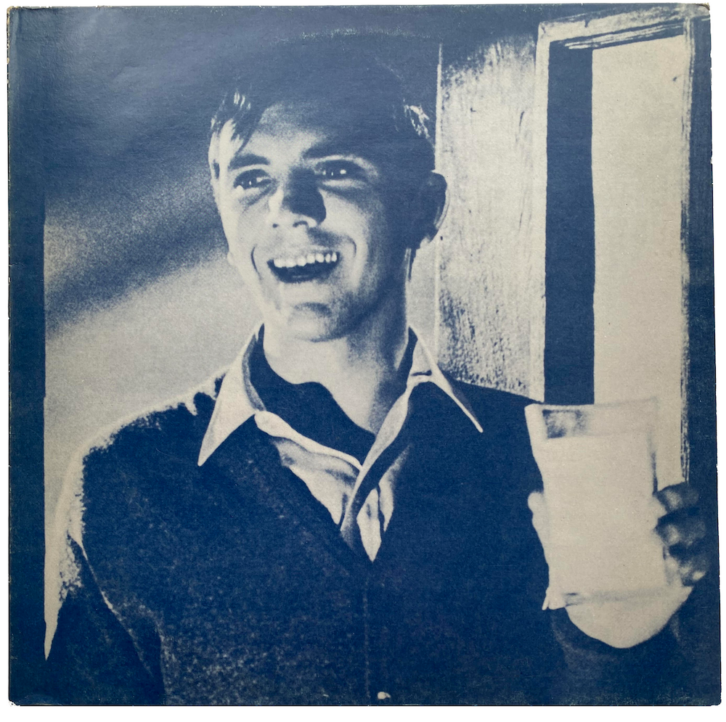

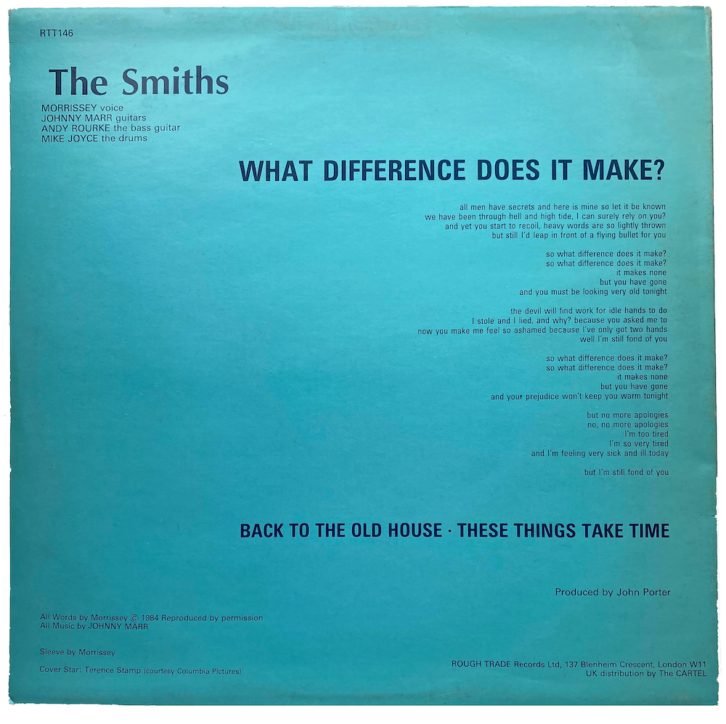

The Smiths made quite an impression when their first album was released in 1984, bringing great guitars back to the synth-drenched New Wave era. The lead singer was Morrissey, ever the enigmatic, ironic poet: “The devil will find work for idol hands to do/I stole and I lied, and why? Because you asked me to/But now you make me feel so ashamed because I’ve only got two hands/But I’m still fond of you hu-ho/So what difference does it make?” Johnny Marr was a modern guitar hero, layering brilliant riffs that served the song rather than celebrating his own virtuosity. And the tight rhythms of bassist Andy Rourke and drummer Mike Joyce kept unusual songs like “This Charming Man,” “Hand in Glove” and this month’s “Classic Track,” “What Difference Does It Make?” on firm ground.

The now-familiar versions of these songs that appeared on The Smiths were produced by John Porter, who was also a frequent contract producer for BBC radio at that time. But Porter was actually the second producer to work on this album. The songs had already been captured with producer Troy Tate, but when Rough Trade label head Geoff Travis heard some rough mixes, he had misgivings, and when he asked for Porter’s opinion, Porter didn’t hold back. “I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll give it a listen, but I’ll need to listen to the master tapes,’” Porter recalls. “So [Travis] booked a studio—I think it was Regent Sound—and they had 14 or 15 songs. I said, ‘There’s a lot to my ear that needs to be redone here.’ To be quite candid, I didn’t think it was very well-recorded. A lot of it was out of tune and out of time, and I said, ‘I don’t know how much money you have left, but I think you’re better off starting again. Everything needs to be fixed.’”

The next thing Porter knew, he was being offered next to nothing to start from scratch and produce The Smiths himself. “I can’t remember what they gave us,” Porter says, “but even by today’s standards, there was hopelessly little money. I think it was probably the equivalent of $3,000 or $4,000 because they’d spent their money already. So we booked a studio in Manchester called Pluto Studios, and we had something like five or six days to cut the record.”

Porter remembers little about Pluto, except that the facility had a helpful staff. However, at the time Pluto was known in some circles as a happening mid-level place off the beaten path; it had hosted sessions with The Clash, Cabaret Voltaire and others. “For the time, it was a very busy studio,” says Phil Bush, then chief engineer at Pluto. “Manchester was a very up-and-coming place, and there was a lot of music about. The proprietor, Keith Hopwood [former rhythm guitarist/backing vocalist for Herman’s Hermits], was writing jingles for TV and radio commercials. The average working week would be jingles three or four days in the week and then you’d get a band in the evening. I was working 18 hours a day sometimes.”

Pluto featured an acoustically dead tracking room and a control room outfitted with a Trident Series 80 console and Studer A800 24-track. Bush engineered The Smiths’ sessions, which comprised basic live band recording to the Studer machine, “more or less with a guide guitar until they had a decent rhythm track,” Bush says. He remembers using a fairly standard mic setup for drums: a pair of Shure SM57s or SM58s on snare, Sennheiser MD441s on toms, a KM84 on hi-hat, and AKG D12 or D24 on kick. What Bush remembers most vividly about hosting Porter and The Smiths is the former’s guitar collection: “It was guitar heaven,” he says. “I’m a guitar player myself, so that’s one thing I do remember is the wealth of wonderful guitars that were there. In particular, a ’54 Telecaster that was absolutely gorgeous!”

Classic Tracks: Big Star’s “September Gurls”

After spending a work-week in Manchester, Porter took his guitars and the band down to Eden Studios (London) where staff engineer Neill King manned one of the first SSL 4000 consoles for some extensive overdub and mixing sessions. By the time the band reached London, Rough Trade had cut a distribution deal with Sire Records, and a bigger budget was found to flesh out The Smiths. This was when the songs really took shape, as Porter added guitar parts and effects to construct dynamics within songs. “What Difference Does It Make?” was one of the tracks that most benefited from Porter’s careful arranging and building.

“When they started playing ‘What Difference Does It Make?’ it was very linear and, for them, it was a long song,” Porter recalls. “It was a 30-bar sequence, which is unusual, and it didn’t have any verse. It was just this thing that started and went. They would start playing and Morrissey would sing, and whenever he didn’t sing they would just carry on and then he would sing again. On a record, that’s not necessarily great because there’s not enough structure, so the first thing I did was put an intro on it.”

Porter’s intro has Marr playing that beautifully recognizable riff before the drums come in. Along with Morrissey’s vocal, it’s the most memorable sound in the track, but it’s only one of the guitar parts that gradually came together for effect. “Every time there’s a particular section, something was added,” Porter says. “On the A section, the second time, we added the harmony guitar on the lick. The second time the B section happened I added another. I’d added two parts to the B section the first time but then we added another harmony. And then on the C section, the same, and then the last time the B section came we added some sound effects, like kids playing in school or something. The first time they played me this song, it was nearly four minutes of licks with no dynamics. Now it starts off with one guitar, and it ends up with 15 or 16 guitars on it.”

Some of those various guitar sounds come from Porter’s guitar arsenal, which King also remembers well. “Back then, they were a struggling band and I think Johnny Marr had a guitar,” King says. “I think a big part of the sound is, because John is a good guitar player himself, he had that collection of different instruments—semi-acoustic, solid body, all kinds of things—that we could experiment with [to get] different sounds.”

“We also put on a backward piano note,” Porter adds. “They were very interested and excited about that. That was something we did subsequently on loads of their records—add a little backward part. And all the time we were doing this, Johnny was very interested in the process, which was great.”

“And then, of course, I remember vocals with Morrissey,” King says. “That was always kind of a kick. We had the studio and control room at Eden linked by a window, and he wouldn’t allow anybody else but John and I to be in the control room and the studio had to be blacked out. He would sit on a stool and turn his back to the control room. That’s privacy for you.”

Morrissey also let his opinions be known regarding any processing of his vocal: “In the early days, he didn’t like any effects on his voice,” Porter says. “As soon as you could hear an effect on his voice, it was a bit of a battle. But I think there’s probably a bit of delayed reverb on that track—it probably was the EMT 250, which we used to call the Tram Driver. It was a 3-foot-high box with levers on top, and it was the first digital reverb. But we would have kept any delay on Morrissey’s voice very, very in the background. I would use loads and loads of effects, but very little of each.”

As for mic choices at Eden, King recalls using a Neumann FET 47 on Morrissey’s voice and a Shure SM57 on Marr’s cabinet, plus an 87 in the room. In contrast to Morrissey, Marr liked to play in the control room with King and Porter close by, while his amp was out in the tracking room. “And all that would go straight into that SSL’s horrible mic preamps in that early board,” King says. “And then, when we got to mixing it, that was the first board with an onboard quad compressor in it so you could just squash the whole track as you were mixing it. We definitely played with that quite a bit.”

“I wasn’t mad about the sound of the SSLs at that stage,” says Porter, who had used SSL boards extensively at the BBC. “The sound wasn’t big, but it was real fun to be able to trigger everything, and you could plug anything into anything with an SSL: the kick drum driving the gates on guitar parts, and percussion parts driving gates that would drive another guitar part, and then chop it up so it sounded like Morse Code.”

Even if some of the technical machinations that went into The Smiths’ recordings were gratuitous, there’s little question that Porter’s production of The Smiths took a really good indie band to great heights sonically. Though the band didn’t really crack open the American album charts till they made their third album—the Morrissey and Marr-produced The Queen is Dead went to Number 2 in the UK and “What Difference Does It Make?” peaked at Number 12. After U.S. fans embraced the group’s later albums, interest in their earlier recordings also grew, and “What Difference Does It Make?” became a staple on modern rock playlists.

The Smiths disbanded in 1987 after releasing the Porter-produced Louder Than Bombs, but the bandmembers each carried on successful music careers—Morrissey most famously. Producer Porter later moved to L.A., where over the course of 20 years he produced projects for B.B.King, Buddy Guy, Ryan Adams, Los Lonely Boys, Bonnie Raitt and more; he recently moved his studio to New Orleans. Phil Bush is still a sound engineer, musician and composer working in Manchester. Neill King, who has worked with artists from Aha to Celine Dion to Green Day, has moved on from the recording industry and is now happily employed in the wine business in Northern California.

“I was lucky enough to work on a handful of huge albums in my career,” King says, “and each time you can tell something special is happening. Recording Elvis Costello, Green Day, The Smiths—you know this is more special than everyday recording studio stuff.”